The Syrian Unity Predicament: Files of Sovereignty, Security, and the Kurdish Issue

The transfer of power in Syria in 2024 did not achieve the desired reconciliation, as the conflict between the interim government and the Syrian Democratic Forces undermined the March 10 agreement and deepened the division over the form of the state between centralization and decentralization. The ambiguity in the agreement and the regional and international interventions, especially from Türkiye, the United States, France, Russia, and Israel, have also contributed to complicating the scene and preventing a stable settlement, which makes the future of Syria linked to the government’s ability to establish a comprehensive and binding social contract that ensures the participation of all components.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – Nov 6, 2025

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

The transfer of power in Damascus in December 2024 offered few opportunities for reconciliation between Syria’s disparate political and military factions. However, the intensified escalation in early October between the new Syrian government led by interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa and the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) confirms that the path to a stable and united Syrian state is still fraught with many obstacles.

Understanding this situation requires an analysis of the two major dynamics surrounding this renewed conflict: the prospects for the sustainability–or collapse–of the March 10 agreement between SDF commander Mazloum Abdi and al-Sharaa and the crucial roles played by regional and international actors–Türkiye, the United States, France, Russia, and Israel–in determining the future trajectory of Syria’s fractured sovereignty.

Escalation Context: Aleppo, October 2025

Deadly clashes between the Syrian army and SDF forces that resulted in families fleeing from major urban centers—specifically in the vicinity of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh, Kurdish-majority neighborhoods in Aleppo city—indicate a serious erosion of peace in the post-Assad environment in Syria.

These clashes broke out after the Syrian army, which had accused the SDF of targeting civilians and members of the army and security forces, redeployed on some axes in the north and northeast of the country, a movement of troops the SDF viewed as a provocative military incursion.

Perhaps even more lethal than these clashes is the broad violation by both sides to the March 10 agreement, which is now on life-support. This is especially true after the Syrian army closed the entrances to the Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighborhoods, thus placing them under siege—despite the March 10 agreement that stipulated that these two communities remain under the local administration of the SDF while they are integrated into national institutions.

Government forces were also reportedly raising earthen berms outside the two neighborhoods, violating a previous agreement to remove these fortifications from public roads. Clashes have reportedly spread to areas of eastern Aleppo and near strategic locations such as the Tishreen Dam, an area previously designated for stabilization and joint patrolling under the March agreement.

The clashes ceased October 7, coinciding with the visits of U.S. Middle East envoy Tom Barrack and Admiral Brad Cooper, commander of the U.S. Central Command and Abdi’s visit to Damascus meeting with political and military leaders, including al-Sharaa in the presence of senior U.S. officials. Many believe this signals the potential for a shift in the positions and approaches of both parties in managing their relationship.

Since the regime change in December 2024 and before the outbreak of the first military confrontation in mixed and densely populated areas, their relationship has been theoretically centered on disputes over governance, including issues of centralization, decentralization, and integration.

The Axis of Crisis: Centralization vs. Decentralization

The instability in Syria is due to the divergence of views between the transitional authority in Damascus and the SDF on the nature of the future Syrian state. Damascus insists on a centralized structure for the country. Al-Sharaa has repeatedly stated that “all weapons must be under state control” and repeatedly rejected federalism or autonomy as a “threat to national unity” and a “red line” that portends division of state.

The SDF and its political wing, the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria(DAANES), oppose the return to the central model that prevailed before 2011. Instead, the SDF adheres to its vision of Syria as a secular, democratic, and federal state. Abdi, following the latest round of high-level talks in Damascus, confirmed this fundamental position: “We are committed to Syrian unity, but any attempt to impose central control without guarantees will be met with a firm stance.”

This ideological and structural opposition has been an obstacle to building genuine trust and reaching a comprehensive and lasting agreement. Moreover, steps the interim government has taken in the region have created doubts about its commitment to inclusivity, especially since they follow a unilateral pattern in the government making decisions related to the form of system and governance, such as the Constitutional Declaration for the Transitional Period issued March 13 or in the process of forming the Higher Committee for the elections of the People’s Assembly on June 13. All of the above has undermined the confidence of the DAANES, along with others involved in Syrian local affairs, including segments of the Druze in As-Suwayda Governorate.

Moreover, parties outside the authorities fear that leadership positions in the new army and security forces will be limited to leaders with an ideological background, particularly former officials of HTS and similar allied factions. This runs counter to the transitional government’s rhetoric on pluralism and its calls for others to engage and cooperate with it. As a result, the government faces difficulties demonstrating flexibility in negotiations with the SDF, especially regarding the latter’s demands to integrate its forces into the newly formed army and security structures.

Even after the March 10 agreement, the SDF remained committed to its decentralization demands. In August, for example, the SDF’s “Unity Conference” in Hasakah sent more explicit messages regarding its vision for a decentralized democratic state and guarantees for Kurdish rights, including the establishment of new provinces with a Kurdish majority. This prompted the interim government to reject the conference outcomes as undermining national unity and an attempt to impose partition, and it canceled talks that had been scheduled between the two parties.

However, the regional and international climate pushes the two parties toward dialogue, yet it is unable to impose a sustainable settlement, making such an outcome unlikely or even impossible, given the current demands of both sides. Pressures from Israel—whether through its ongoing incursions into the south or its preference for a decentralized system of governance in Syria—indirectly intersect with the demands of minorities in the country for autonomy or administrative decentralization, such as the Druze in As-Suwayda or some Alawite leaders on the coast. In this context, Damascus conflates the legitimate rights of minorities with the seriousness of their demands and Israeli threats to Syria’s sovereignty.

March 10 Agreement: Fragile Integration Plan

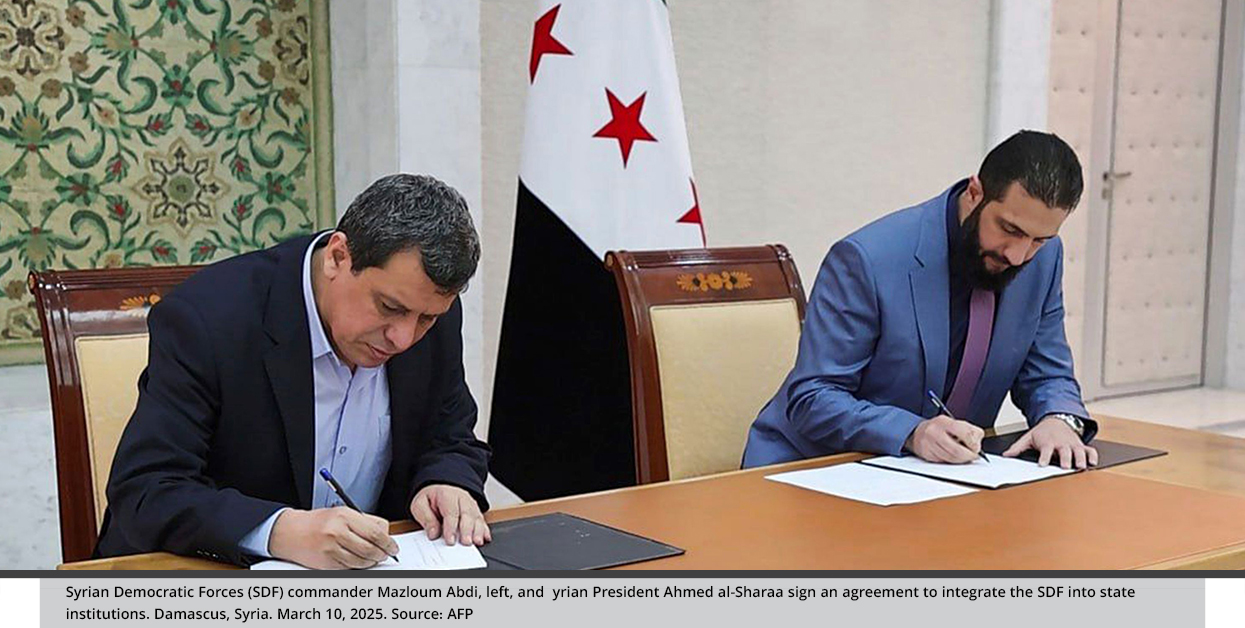

The agreement, signed on March 10 between al-Sharaa and Abdi, was widely hailed as a historic achievement aimed at ending the deep division between Damascus and the DAANES. However, the document’s ambiguity, along with the conflicting interpretations by all concerned parties, has hindered its implementation, stalled its development, and perhaps even undermined the negotiating framework itself.

Whereas the basic terms of the agreement set a path toward the reintegration of the northeast into the structure of the Syrian state, the agreement’s attempt to reconcile conflicting strategic demands—by recognizing Kurdish rights (the United States, France, and the SDF) while enforcing full institutional integration (Türkiye and Damascus)—created structural ambiguity.

This ambiguity quickly turned the mechanism of military integration into a complex issue. In essence, the SDF viewed integration as its forces joining a reformed national army within the framework of a restructured state, while regarding the surrender of its weapons and the dismantling of its forces as a fundamental “non-negotiable” red line. Consequently, its negotiators have demonstrated flexibility in preparing for integration, but only through a gradual process that allows the SDF to maintain command independence or eventually become a recognized unified bloc within the broader military structure.

In contrast, Damascus and Ankara interpreted the integration mechanism as a temporary absorption of SDF forces, followed by the dismantling of independent structures while maintaining an army framework that includes HTS leaders and elements. This stance is particularly strategic for Türkiye, which views the SDF as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), classified by Ankara as a terrorist organization.

Accordingly, Türkiye emphasizes its demands for the SDF’s complete disarmament, the immediate withdrawal of all foreign fighters and senior PKK-affiliated cadres, and the integration of any remaining personnel into a 100% centrally administered national army. Damascus aligns with this position, asserting that parallel armed entities threaten national sovereignty.

As a result, Syrian officials accuse the SDF of moving too slowly and pursuing decentralized ambitions that could lead to fragmentation, while SDF officials accuse the government of attempting to “dissolve the SDF under the guise of integration,” particularly given the continued presence and hostile operations of Turkish-backed militants in northern Syria—which Damascus has not condemned. Consequently, the SDF fears that relinquishing its weapons would mean surrendering its political structure, represented by the DAANES, and facing an existential threat.

Additionally, interpretations are becoming increasingly complex regarding economic sovereignty. Although the March 10 agreement provides for the integration of economic institutions, including oil and gas fields, the SDF continues to maintain quasi-independence in the economically vital Al-Jazira region. It views its control over natural resources and border crossings as essential for sustaining its authority in the DAANES areas, relying on them to provide basic services in the northeast. Consequently, relinquishing these resources would constitute an irreversible concession, making this issue a continuous and fundamental point of dispute.

Geopolitical Landscape: The Impact of Actors

The disagreement and disparities between the interim government and the SDF intersect with both external and internal factors. While fundamentally a crisis over sovereignty, resources, and power-sharing, the positions and approaches of external actors play a major role in shaping the dispute and its developments, particularly with regard to five regional and international players: the United States, Türkiye, France, Russia, and Israel.

On one hand, the United States maintains a diplomatic rhetoric centered on stabilizing and unifying the country by the establishment of a centralized but more diverse and representative government, particularly inclusive of minorities such as the Kurds.

Hence, the U.S. policy of conditional support links sanctions relief and broader economic engagement with the Syrian government to its ability to adopt an inclusive approach toward all Syrian communities. Consequently, Washington plays a key role in the negotiations between the interim government and the SDF. As Barrack and Cooper attended the Al-Sharaa and Abdi meeting, they continued to ensure adherence to the March 10 agreement and urged its development.

By supporting the transitional government while protecting the SDF from collapse (particularly given the SDF’s demands for political integration with Damascus), the dual U.S. strategy aims to preserve the gains made against ISIS while strengthening Syrian unity. This is especially significant as the U.S.-led Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) continues its mission to combat ISIS and maintain a presence in northeastern Syria.

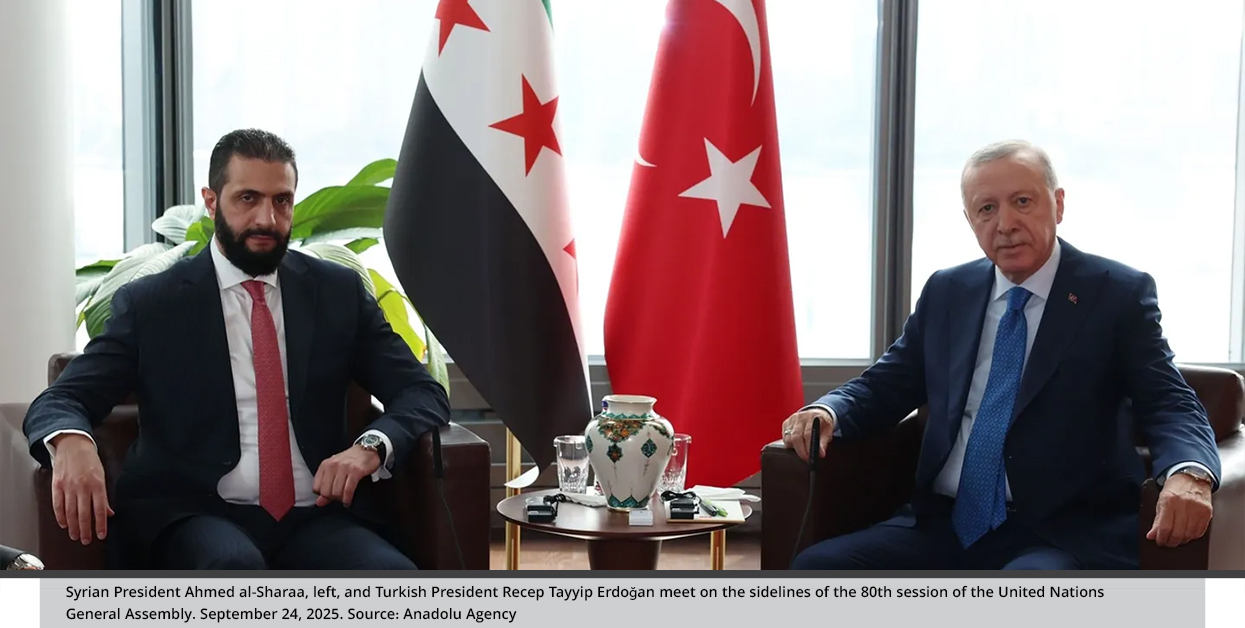

On the other hand, Türkiye views the SDF as a current threat, making its management one of the country’s most pressing national security concerns. Accordingly, Türkiye does not accept compromise on its demands for the complete disarmament of the SDF, the removal of all foreign fighters and high-ranking cadres linked to the PKK, and the full integration of the remaining forces into the Syrian army.

While this position gives the Syrian interim government a decisive leverage in pursuing these demands, it simultaneously also reduces its maneuverability and independence in the negotiation process. One indication of this tension is al-Sharaa’s warning that if the SDF fails to fully integrate by the end of 2025, Türkiye may resort to large-scale military action despite the challenges posed by U.S. opposition to any such action, Türkiye’s concern over destabilizing its fragile understanding with the PKK, and other potential local repercussions within Türkiye.

Conversely, any Turkish military action is likely to exacerbate Türkiye’s geopolitical rivalry with Israel in Syria. Israeli security measures, primarily focused on the southern border, significantly influence the dynamics in the northeast by altering the priorities of Damascus and U.S. diplomacy in Syria, thereby weakening the Syrian interim government’s negotiating position.

More importantly, the United States is actively brokering a stringent security agreement between Syria and Israel. The SDF understands this context, which is why the DAANES is likely to maintain the status quo and avoid advancing the March 10 agreement pending a U.S.-brokered resolution of the security arrangement.

At the same time, if a security agreement between Syria and Israel is successfully concluded—perhaps by the end of 2025—it would bolster the Syrian interim government, reduce Washington’s urgency regarding the complex Kurdish issue, and thus encourage Damascus and Türkiye to impose a military deadline.

On the crisis front, France occupies a unique diplomatic position as the main European advocate for Kurdish political aspirations and the model of the DAANES. French foreign policy regards the Kurdish issue as central to a lasting Syrian solution, recognizing the DAANES as a practical framework for managing diversity, protecting minorities, and countering extremism. In its engagement with the interim government in Damascus following the regime change, Paris insisted that it implement political reforms, ensure accountability for war crimes, and, most importantly, broaden political participation for Kurds, Alawites, and Druze.

From Loose Rhetoric to Legal Social Contract

Finally, it appears that both parties have failed to adopt a flexible, open approach to dialogue and to turn the March 10 agreement into an opportunity for comprehensive unity, overcoming obstacles arising from divergent interpretations, mutual distrust, and ideological differences.

Meanwhile, the Syrian interim government, as the representative of the country’s sovereignty, continues to face demands for greater transparency toward minorities. The internal dispute is not limited to the SDF but also involves the Druze and Alawite communities, highlighting the need for state and defense institutions to accommodate the various components of the Syrian population rather than allowing a single party to monopolize power and public positions.

Consequently, the government must demonstrate a concrete commitment that goes beyond rhetorical guarantees of citizenship rights by establishing explicit constitutional provisions for the rights, representation, and participation of all communities in the new power structure. Such measures constitute a social contract that regulates the relationship between the state and society in all its diverse components.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية