The Syrian Situation Between Centralization and Decentralization Options

The issue of centralization versus decentralization in Syria is a structural one that goes beyond intellectual debate, touching on the very essence of state reconstruction, the definition of national identity, and the form of governance. While centralization is viewed by some as a safeguard for the country’s unity, experience has shown that it has deepened marginalization and weakened political participation. Conversely, many political segments see decentralization as an entry point for comprehensive institutional reform; however, hastily adopting it could threaten stability and sovereignty, especially given the complexities of the Syrian reality.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – Oct 14, 2025

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

The issue of centralization and decentralization constitutes one of the core dimensions for understanding the current Syrian crisis. It is not merely a technical debate over models of governance and administration, but rather extends to encompass questions of national identity and the balance of relations among societal segments, making it a decisive factor in shaping the country’s political and economic future.

This report focuses on providing an in-depth analysis of the concept of centralization and decentralization in the Syrian context by tracing its historical roots, unpacking its political and social dimensions, and assessing the positions of local and international actors toward this issue. It also seeks to present possible scenarios for the trajectories of decentralization in Syria, in light of ongoing transformations and the structural challenges facing the state’s reconstruction.

Theoretical Framework: Definition and Models

Analyzing the issue of centralization and decentralization in the Syrian context requires a precise distinction between the two concepts, given the institutional and political implications each entails. Centralization is the concentration of decision-making authority within a single power or a specific entity, limiting the ability of lower levels to take initiative and act independently. Decentralization is the process of transferring authority and responsibilities from the central government to lower levels of governance, such as local councils, regional governments, or municipalities, thereby enhancing the ability of these entities to manage their affairs in accordance with their local specificities.

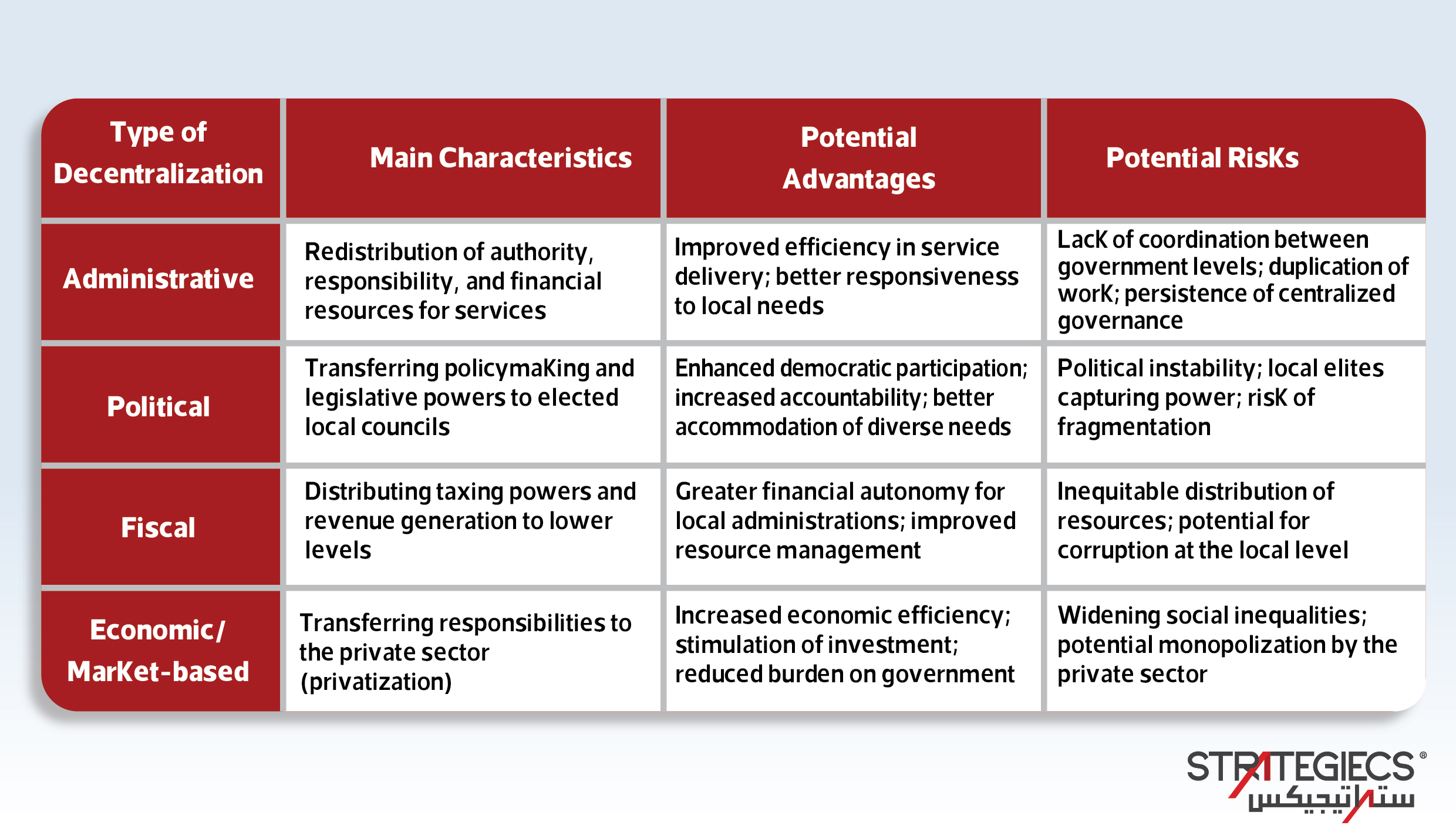

Two types of decentralization:

Administrative decentralization: In this model, administrative powers are delegated to local councils, while the central government retains the authority to make final decisions on fundamental issues. It is often employed to improve the efficiency of delivering public service through the redistribution of powers, responsibilities, and financial resources.

Political decentralization: This entails transferring policymaking and legislative powers from the central authority at the national level to democratically elected bodies at the local level, thereby allowing broader representation of local communities in the decision-making process.

Summary of the characteristics of decentralization:

In the Syrian context, distinguishing between the different types of decentralization is not merely a theoretical or academic matter, but rather a core axis of the ongoing political disputes. Current debates on decentralization in Syria reveal a structural contradiction between two opposing visions.

The first views decentralization as an essential prerequisite for achieving political stability and building a modern state, considering it a necessary entry point for restructuring the state on democratic and participatory foundations.

The opposing view, however, supports decentralization as a future option to be pursued only after stability has been achieved. Without such stability, decentralization is feared to become a potential factor in state fragmentation, particularly in light of persistent societal divisions and ongoing security tensions.

This divergence of positions reflects the complexity of the Syrian reality, where the issue of decentralization intersects with political and security dynamics, making it one of the most sensitive matters in the state-building process. The contradiction in viewpoints also constitutes one of the main obstacles to reaching political consensus, as it raises existential concerns among the different parties and requires a comprehensive rethinking of the relationship between the center and the peripheries within an inclusive national framework.

The sensitivity surrounding political decentralization, whether in terms of rejection or acceptance, may be traced back to the historical legacy of strict centralized rule that prevailed for decades, particularly during the era of the Ba’ath Party. Power and resources were systematically monopolized, leading to the marginalization of local peripheries and the weakening of institutional structures outside the center. This context has left a profound impact on political discourse and public debates regarding the viability of adopting a decentralized model, creating a climate of hesitation toward any institutional reforms that might result in an actual redistribution of power.

Centralization as a Means of Preserving National Unity

The Syrian landscape shows broad adherence—including among segments of the opposition—to the idea of a strong centralized state, which is seen as a guarantee for the country’s unity amid current challenges. This stance does not necessarily stem from support for the previous regime, but rather it reflects deep-seated fears of state fragmentation due to the deterioration of the social fabric in recent years. In this context, calls for political decentralization or federalism are met with considerable skepticism, as many actors view them as a potential gateway to the division of Syria.

These concerns are further reinforced by reference to regional examples where federal systems were implemented in fragile social environments, with political decentralization in some cases exacerbating ethnic and sectarian divisions and prompting local authorities to argue over resources and powers. This, in turn, weakened the central state and reduced its ability to maintain national balance. Within this framework, fundamental questions arise regarding the feasibility of applying a decentralized model in Syria, given the absence of internal political consensus, the multiplicity of local loyalties, and the uneven levels of institutional readiness across regions.

On the other hand, opposition to political decentralization in Syria is partly fueled by the political memory of past foreign-backed division projects, foremost among them the Sykes–Picot Agreement, which is still invoked as a symbol of the fragmentation of the region’s political geography. In this context, some representatives of the current authorities view decentralization as a continuation of external agendas aimed at undermining state unity and weakening central authority.

Not limited to the authorities alone, this perception resonates with large segments of the traditional opposition who see political decentralization—particularly federalism—as a threat to the country’s unity and consider it a “softened label” for plans of partition.

Challenges of Sustained Centralization

Although pro-centralization discourse often relies on security and nationalist considerations aimed at preserving state unity, the Syrian experience has shown the limitations of this model in the long term. The adoption of a highly centralized, authoritarian governance system in previous decades produced counterproductive outcomes, including the monopolization of power and resources by a narrow elite, the neglect of peripheral regions, and the marginalization of societal segments outside the center.

This concentration of decision-making and resource allocation deepened developmental gaps between the capital and the provinces, resulting in stark disparities in services and infrastructure, which in turn reinforced feelings of marginalization and exclusion. It is unsurprising that this popular discontent accumulated over time, eventually becoming one of the main drivers of the movement that erupted in early 2011—an indirect expression of rejection of the centralized model and the lack of fairness in the distribution of power and wealth.

From a legal and institutional perspective, several experts and legal scholars point out that the centralized governance model—with its inherent resistance to granting local authorities meaningful decision-making autonomy—has proven limited in responding to citizens’ daily needs. It has led to shortcomings in the provision of basic services and an inability to address diverse local challenges, thereby deepening the gap between the state and society.

This shortcoming is considered one of the structural factors that contributed to the outbreak of the Syrian conflict, which exposed the fragility of the centralized model and its inability to manage societal diversity or ensure equitable resource distribution. Thus, centralization shifted from being a tool for preserving social unity to becoming a catalyst for social and political divisions, fueled by the accumulated marginalization and exclusion across various Syrian regions.

Decentralization as a Tool for Consensus and State-Building

In non-governmental Syrian political discourse, decentralization is proposed as one of the potential institutional options to strengthen national consensus and reorganize the relationship between the state and its societal segments. Supporters of this model consider it a veritable lifeline for preserving the country’s unity by redistributing power in a way that respects social pluralism and enhances the effectiveness of local governance.

The significance of decentralization extends beyond its political dimension in building a consensual governance system; it also addresses a range of structural challenges within Syrian domestic politics, most notably the historical marginalization of peripheral regions, weak public service delivery, and the imbalance in resource distribution. Decentralization is also a key tool for reinforcing the principle of citizenship and expanding popular participation in decision-making, thereby strengthening the democratic process and limiting the recurrence of authoritarian governance patterns.

Several experts view decentralization as a fundamental safeguard against the emergence of new dictatorships by dismantling the monopoly of power and broadening the base of local representation. This perspective also draws legitimacy from Syria’s own legal heritage. Constitutional and legislative documents such as the 1973 Constitution and the 1956 Local Administration Law, which established principles of administrative decentralization, provided a legal foundation upon which a more comprehensive and sustainable decentralized model can be developed.

Practical Challenges and Risks of Implementing Decentralization

The presence of political or legislative or societal will alone is not sufficient to ensure the successful implementation of decentralization in Syria. The process faces a range of structural challenges and practical obstacles that could undermine its effectiveness. At both the administrative and financial levels, developing countries attempting to adopt decentralized models often encounter barriers such as weak institutional support from the center, persistent centralization in decision-making, and the failure to adequately transfer financial resources to local authorities.

Institutional capacity-building at the local level is also among the most significant challenges facing the shift toward decentralization, especially in contexts marked by stark developmental disparities between the center and peripheral regions. The absence of administrative expertise, weak infrastructure, and uneven levels of institutional readiness undermine the ability of local entities to exercise their powers effectively, threatening to reduce decentralization to a mere formal measure that fails to achieve its developmental and political objectives.

In the same context, more complex political and security concerns arise regarding the implementation of decentralization, particularly given the fragility of the Syrian state and the multiplicity of local actors. Some fear that delegating authority from the center to local authorities could empower local elites to dominate governance within their regions, potentially giving rise to multiple, extreme forms of authority that reproduce authoritarianism in fragmented ways and weaken the state’s ability to maintain unified decision-making and national sovereignty.

All of these concerns are an extension of greater fears related to the fragmentation of the state, as political decentralization is viewed in some circles as a potential gateway to dismantling Syria and increasing institutional deterioration, rather than serving as a tool for reconstruction.

This perception is reinforced by the absence of institutional safeguards, the multiplicity of loyalties, and the uneven levels of readiness across regions, making the implementation of decentralization a challenge that requires a careful and gradual approach—one that balances the enhancement of local participation with the preservation of state unity.

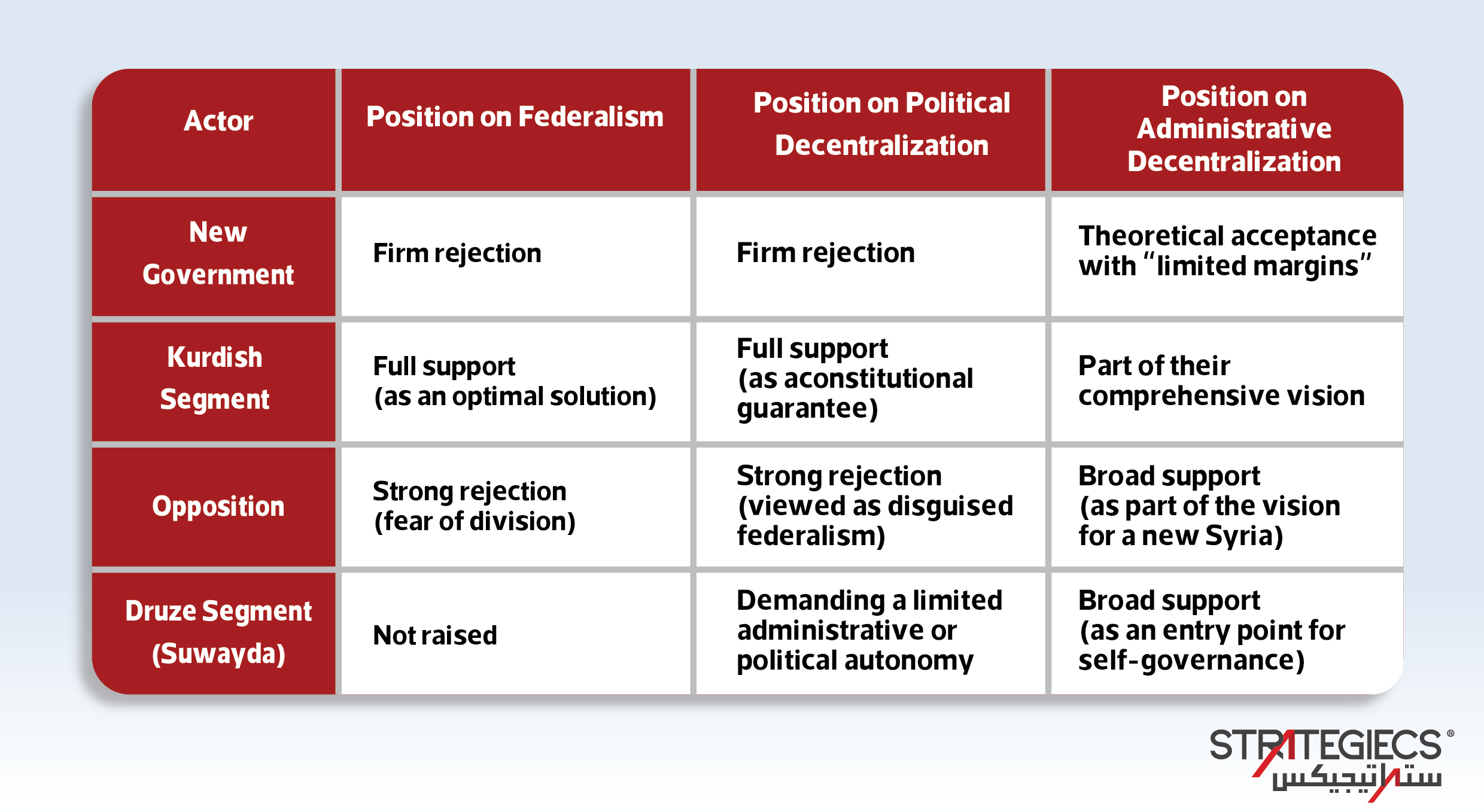

Power Dynamics and Positions of Key Actors

As previously noted, the positions of actors in the Syrian arena regarding decentralization vary significantly. This variation stems from each party’s interest in defending its political objectives, its regional and local alignments, and the nature of its influence on the ground. The stance on decentralization is therefore not based solely on theoretical or institutional considerations but is shaped within complex contexts of political competition, alliances, and security concerns.

In this context, the positions of the main actors can be classified as follows:

First: Position of the New Government in Damascus

Historically, the Syrian regime has taken a stance rejecting “comprehensive decentralization,” driven by fears that it could lead to state fragmentation and undermine national unity. This approach has continued under the current transitional government, which firmly rejects any proposals for federalism and insists on maintaining state centralization as the governing framework.

However, the government shows a theoretical willingness to grant limited administrative decentralization. Some view this as a continuation of the policy of monopolizing power, as within central governance institutions, any reduction in central authority is seen as a direct threat to state influence.

From this perspective, the acceptance of limited administrative decentralization can be interpreted as a tactical move aimed at creating an impression of political openness without being translated into an actual shift in the structure of power or a genuine redistribution of authority.

Second: Position of the Kurdish Segment

The Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria, represented by the Syrian Democratic Council, is one of the main actors supporting political decentralization, including the federal model. This stance is based on a vision that views federalism as a constitutional guarantee for the rights of national segments—primarily the Kurds—and as an effective means to achieve fair participation in managing state affairs.

To reinforce the legitimacy of its demands, Kurdish political discourse frames federalism as an organizational form of voluntary unity. It is not intended to divide the country but to prevent the monopolization of power by a single group and to strengthen the balance between the center and the peripheries. The expanded decentralized model is thus viewed as an institutional framework that allows for greater political representation of all segments and contributes to building a multi-identity state based on principles of partnership and democracy.

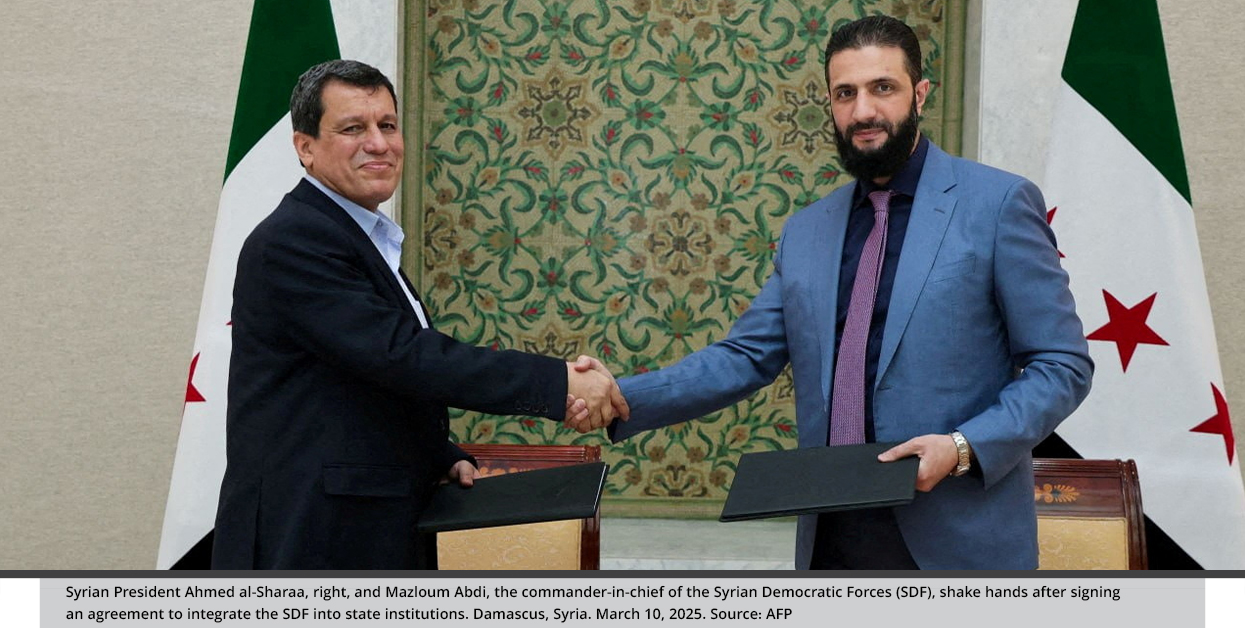

What distinguishes the Syrian Democratic Forces from other actors supporting decentralization is their possession of an organized and effective military force on the ground. This gives its demands a dimension that goes beyond administrative or constitutional debate, reaching the level of conflict over national sovereignty and the redefinition of the relationship between the center and armed segments. The existence of a military force independent of traditional state institutions is a decisive factor in reshaping power balances and it poses fundamental challenges to any project aimed at rebuilding the Syrian state on decentralized foundations.

The failure to integrate Kurdish forces into the official military structure is one of the key issues intensifying this tension. The continued existence of an armed force outside the framework of the central state fuels fears that political demands could evolve into separatist measures encompassing security, administrative, and economic aspects. Consequently, the issue of decentralization in this context cannot be separated from the broader debate on the future of the nation’s official military institution, the unity of sovereign decision-making, and the shape of the state in the post-conflict phase.

Third: Position of the Syrian Opposition

The positions of the Syrian opposition regarding decentralization, particularly federalism, are marked by clear divergence, reflecting the plurality of political references and varying visions for the future of the state. Most opposition factions reject the principle of federalism and are cautious about political decentralization based on a range of historical and political considerations. These include a lack of trust in the intentions of actors advocating federalism as a political option and concerns that it could undermine a unified national identity in favor of the rise of subregional or ethnic identities.

Conversely, some Syrian opposition factions adopt a more flexible stance toward decentralization, supporting the idea of “expanded administrative decentralization” as part of a project to build a new democratic state that reorganizes the relationship between the center and local communities on fairer and more effective grounds.

However, analysis of opposition positions reveals that their understanding of decentralization often diverges from the prevailing international perspective, which views it as a tool for power-sharing within a negotiated framework with the existing government. Instead, they approach it as a means to completely change the system rather than as an instrument for redistributing authority within a political settlement.

This interpretation, which conflicts with international approaches, has weakened the opposition’s ability to present actionable proposals, negatively affecting its negotiating position and reducing the prospects for building a sustainable national consensus.

The Case of the Druze in Suwayda

The situation of the Druze community in the Suwayda Governorate is a microcosm reflecting the broader complexities of the Syrian landscape, particularly regarding decentralization and the redistribution of power. Some community leaders and local references have expressed a clear inclination toward demanding self-governance or administrative autonomy, understood within the framework of preserving state unity and avoiding explicit calls for secession or partition.

The Druze’s demands center on establishing a civil state governed by a constitution that guarantees equal rights for all citizens and reinforces the principles of justice and citizenship. This position is accompanied by a clear and firm stance toward the new transitional authority, as the community has expressed a lack of trust in the Damascus government’s ability to represent local aspirations or ensure the desired reforms.

The Druze position plays a significant role in highlighting the particular dynamics between local identities and the political center, as well as the importance of building a governance model that accommodates social pluralism without compromising state unity. This is especially critical given the rising local demands and declining trust in the center.

Moreover, the Druze insistence on decentralization has evolved beyond a purely local concern, becoming part of intertwined regional and international dynamics. The meetings in Amman on August 12—which brought together representatives from Jordan, the Syrian transitional government, and the U.S. envoy—demonstrated how the Suwayda issue has shifted from an internal matter to a political issue discussed within broader regional agendas.

This means that the Druze’s demands, previously framed within a limited administrative context, are now leveraged as part of political pressure on the new central government. External actors increasingly view the Suwayda issue as a bargaining tool that can be used to reshape power balances within Syria or to push for institutional reforms that go beyond the local level, giving the matter a strategic significance that extends beyond the boundaries of the governorate.

On another front, amid growing regional and international attention to the Suwayda issue, the Druze community seeks to adopt a political discourse that warns against the exploitation of its demands by external actors and the transformation of these demands into tools of geopolitical pressure.

Finally, the issue of centralization and decentralization in Syria is a structural matter that goes beyond theoretical debate to touch the very core of state reconstruction. It is not merely a technical choice in organizing authority; it reflects differing visions regarding national identity, forms of governance, and the future of coexistence among societal segments. While some view centralization as a guarantee for national unity, historical experience has shown that it has sharply deepened marginalization and significantly weakened political participation.

Conversely, although several Syrian political actors and segments support a decentralized system as a means for comprehensive institutional reform, rushing its implementation carries risks related to stability and sovereignty, especially given the complex Syrian context. Overcoming this contradiction requires all Syrians to reach a consensus on a gradual and comprehensive approach, one built on national dialogue and mutual trust among all their segments and factions.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية