Will ISIS Succeed in Hijacking Syria from the Transitional Government?

Since the fall of the previous regime in December 2024, ISIS has been taking advantage of the fragility of the Syrian transitional authority and the overlapping structure of its various factions with a renewed surge in activity. Despite intensified international strikes against it, ISIS has managed to carry out sophisticated attacks reposition itself amid the complex political and security challenges facing the interim government. The situation is further complicated by the emergence of even more extremist groups and the erosion of boundaries between regular forces and armed extremists. Meanwhile, the international community’s support for the new government is tied to its seriousness in combating terrorism and extremism—thus placing a structural challenge on the government’s security institutions and internal alliances.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – Aug 4, 2025

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

ISIS activities have significantly escalated in Syria since the fall of the previous regime in December 2024, as confirmed by multiple reports regarding the arrest of active ISIS cells and the organization’s attacks on security forces and the transitional government’s army. This escalation has been accompanied by a clear intensification in ISIS’s rhetoric, openly declaring hostility toward the new authority and rejecting its conciliatory discourse with the West and the international coalition.

This resurgence, however, cannot be interpreted merely as a traditional comeback following a period of chaos. Rather, it reflects a qualitative shift in ISIS’s tactics to exploit the fragility of the transitional authority and its entanglement with various factions and armed groups. These complex dynamics have created an environment conducive to the group’s repositioning and expansion, placing the transitional government before an extremely complicated challenge—one that is not limited to its operational capacity to respond to the threat, but extends to its ability to manage alliances and rebuild security institutions with clear loyalties and identities, capable of confronting terrorism without being infiltrated or surrounded by gray zones that are difficult to distinguish from the adversary itself.

Indicators of ISIS’s Resurgence and Expansion

ISIS has notably regained its operational activity following the regime change that took place in December 2024, with the subsequent months witnessing a rise in the group’s attempts to carry out attacks, amid intensive efforts to contain it. On January 11, 2025, security forces affiliated with the interim government foiled a serious plot targeting the Sayyida Zainab shrine—a prominent religious symbol for the Shiite community. This was followed by a series of security operations that led to the arrest of the ISIS leader known as “Abu al-Harith al-Iraqi,” and the dismantling of affiliated cells in Daraa Governorate on February 18, in the city of As Sanamayn on March 6, and finally the arrest of another cell in Aleppo on May 17, where a suicide bombing resulted in deaths and injuries among security personnel of the transitional government.

In mid-May, ISIS succeeded—for the first time—in executing two simultaneous attacks targeting security and army forces: one in Deir ez-Zor and the other in As-Suwayda Governorate. At the same time, ISIS continued its operations in areas controlled by the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration, headed by the Syrian Democratic Forces. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented approximately 60 ISIS attacks between January and mid-April 2025.

These incidents—particularly those occurring in areas under the transitional government—coincide with a clear hostile stance declared by ISIS against the new authority. This was manifested in the group’s first video statement issued on January 25, in which it attacked the speech of General Commander Ahmad al-Sharaa, describing it as submission to the conditions of the international coalition. In a subsequent statement released on April 20, ISIS escalated its tone, directly threatening Al-Sharaa over his potential alignment with The Global Coalition Against Daesh.

In reality, the transitional government faces a complex political and security dilemma in its confrontation with ISIS. the latter is exploiting the fragile and heterogeneous composition of the new authority, which includes factions and components that share, to some extent, ideological overlaps with ISIS. ISIS has capitalized on this gap: in its official newsletter Al-Naba, published in mid-May, ISIS called on foreign fighters—including several hardliners—as well as discontented members of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham to defect and join its ranks.

This appeal came in the wake of internal defections within the extremist current on the Syrian scene, which have led to the emergence of new takfiri entities, such as Saraya Ansar al-Sunnah. While this group shares ISIS’s hardline view of the transitional government, it differs in its objectives and operational tactics.

Regional and International Response to the Potential Threat of ISIS

Regional countries and international actors moved swiftly in the immediate aftermath of the regime change to prevent ISIS and other terrorist groups from exploiting the security vacuum and capitalizing on the political chaos in Syria. The response took various forms, including preemptive and preventive military strikes, intensified security and intelligence coordination, and the formation of specialized counterterrorism task forces among countries in the region—particularly Syria’s neighboring states.

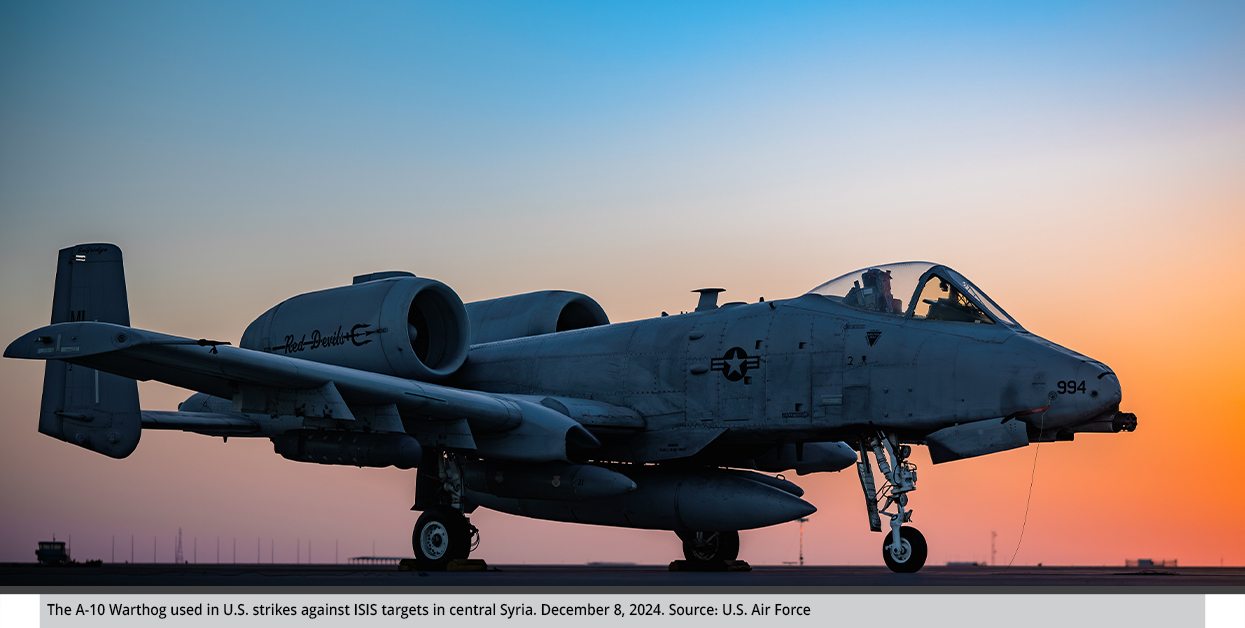

The United States launched its first measures the day after the regime change, when U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) carried out focused airstrikes targeting over 75 ISIS positions and facilities in central Syria. These included training camps, command centers, and weapons depots, and were conducted using fighter jets and B-52 bombers.

This was followed by additional U.S. air strikes on ISIS camps on December 16, 2024. Then, on December 19, an American strike killed a senior ISIS commander in Deir ez-Zor. On December 23, another strike targeted a truck carrying weapons for the group, also in Deir ez-Zor.

By late December, France joined the operations, launching its first strikes against ISIS since the regime change. The French attacks targeted weapons depots and a command center in the eastern countryside of Homs.

Similarly, the region—particularly Syria’s neighboring countries—witnessed swift action in response to the potential threat posed by ISIS. The Riyadh Conference, held on January 12, 2025, included discussions focused on supporting Syria in its efforts to combat terrorism.

In February 2025, Syria and neighboring countries—Türkiye, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon—established a five-party security alliance dedicated to counterterrorism. This alliance held a high-level meeting March 9 in the Jordanian capital of Amman attended by foreign and defense ministers, along with military and intelligence leaders. The meeting resulted in the formation of a multinational operations center—Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR)—to oversee coordination of military operations against ISIS and facilitate the exchange of intelligence among its member states.

Meanwhile, Western countries, led by the United States, have made the new authority’s commitment to combating ISIS a precondition for establishing relations and lifting sanctions on Syria. France, for instance, linked its relationship with the transitional government and its support for the transitional process to several key issues, including the fight against extremism and terrorism—a stance highlighted during this February’s Paris Conference on Syria.

Likewise, the United States also presented a list of conditions to the new government in April, which included taking concrete measures against terrorist organizations and extremist ideologies as a prerequisite for lifting sanctions. And Germany’s Foreign Ministry announced in May that its support and cooperation with Syria are contingent on the transitional government’s genuine efforts to counter terrorism.

Although Washington partially eased sanctions in June, it emphasized that this should not be interpreted as a retreat from its demands. Rather, it is considered a test step—a provisional measure dependent on the new government’s continued commitment to meeting the outlined conditions, particularly regarding counterterrorism and the fight against extremism.

The Dynamics of Complexity and Threat Between the Authority and Terrorism

Despite the preemptive strikes carried out by the United States and the international counterterrorism coalition—along with regional and international efforts aimed at containing the extremist threat—ISIS has succeeded in regaining a portion of its operational momentum. The group managed to carry out its first operations in May to reposition itself and signal its plan for future attacks.

On one hand, this escalation is unfolding within an extremely complex context, marked by a deeply entangled political and security landscape. The institutional, security, and military structures of the transitional government remain fragile, composed of a broad spectrum of armed factions with diverse backgrounds—ranging from moderate groups to others that, to varying degrees, have a shared ideology with extremist currents. This indirect overlap between certain elements of the authority and radical ideologies risks creating a grey zone that offers terrorist organizations room to maneuver and infiltrate. Such ambiguity complicates the transitional government’s efforts to establish stability and assert effective control on the ground.

On the other hand, the transitional government faces a dual challenge: building enough trust with the international community—particularly the West—to get the sanctions lifted permanently while also dealing with internal unrest fueled by terrorist organizations exploiting the opposition’s arguments against openness to the West. This tension affects the delicate balance within the power structure, especially regarding foreign fighters and extremist factions such as the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement and Sham Legion.

Hypothetically, the ability of ISIS and other terrorist organizations to operate and recruit increases as the transitional government both becomes more open to the West—particularly in its relationship with the United States—and adopts rhetoric that is not explicitly hostile toward Israel. For instance, the day after Trump met with al-Sharaa during his visit to Saudi Arabia in May, reports emerged of Syria’s security campaign targeting foreign fighters’ bases in Idlib and Hama.

Although the Syrian Ministry of Interior denied the reports, they may serve as a warning to foreign fighters and other extremist groups against taking a stance on the shifting direction of Syria’s international relations—or a warning against responding to ISIS’s call, which had been issued just days before the incident was reported and then denied.

Moreover, despite the absence of explicit opposition from hardline factions within the transitional government toward its political discourse or external openness—something that, in practice, grants it a broader margin of maneuverability in security coordination and intelligence exchange with neighboring countries and the international community, thereby enhancing its image as a serious authority in counterterrorism—this apparent stability conceals a more complex issue.

The conceptual distinction between “terrorism” and “extremism” remains a central dilemma for the transitional government, especially given the international community’s insistence on addressing both as a condition for continued support and political and diplomatic engagement. While the government demonstrates a relative commitment to combating terrorism to ensure national security, confronting manifestations of ideological and doctrinal extremism remains far more complicated.

While terrorism traditionally manifests as a reaction to the transitional government’s foreign policy—particularly regarding its relations with the United States and Israel—extremism reveals a deeper face within the Syrian social fabric. It does not merely oppose the discourse of openness or reconciliation, but is clearly evident in hostile attitudes toward minorities and, in some cases, through active participation in violations and abuses against minorities.

This form of violent extremism against pluralism has led to profound shifts in the structure of terrorist rhetoric. New violent groups have emerged, driven ideologically and operationally by the rejection of the “other.” Among the most prominent of these is Saraya Ansar al-Sunnah, a new anti-Shia, anti-Alawite, and anti-Druze Islamist militant organization that has raised the banner of opposition to the transitional government’s “conciliatory discourse” toward religious and social minorities.

Since it emerged this January, the group has claimed responsibility for several deadly attacks targeting religious and civilian components, most notably the June 22 bombing of Mar Elias Church in Damascus. This marks a dual escalation in the nature of targeting—from conflict with the authorities in the case of ISIS to conflict with society itself in the case of other extremist and terrorist organizations.

Within the complex challenges facing the Syrian transitional government in combating terrorism and extremism, a more serious operational crisis has emerged: the erosion of clear boundaries between regular security and military forces and the extremist armed elements that have infiltrated or merged with the framework of organized command and control.

This issue became evident during the March 6–10 events on the Syrian coast when armed elements outside the official security and military formations engaged independently in combat operations without central coordination. This pattern recurred again in the As-Suwayda Governorate, where, according to the U.S. special envoy to Syria, individuals believed to be affiliated with ISIS carried out field executions against members of the Druze community—and security agencies were unable to intervene or distinguish them from regular forces due to their wearing uniforms and bearing equipment similar to those used by the official army and security forces.

This overlap in the theater of operations undermines the state’s ability to control military actors, weakens the transitional government’s credibility with its international partners, and grants terrorist and extremist organizations additional capacity to maneuver and hide under the cover of authority.

In conclusion, despite the tangible operational and intelligence efforts demonstrated by the transitional government in pursuing ISIS cells across Syria, a more advanced analysis clearly shows that combating terrorism and violent extremism requires a broader and deeper approach. This approach should not be limited to security responses but must originate from within the structure of the authority itself, necessitating a thorough reassessment of the transitional government’s alliances—particularly with the hardline factions within its ranks and foreign fighters.

This also indicates that the rehabilitation of the army and security forces should not be confined to organizational aspects alone but must include building a clear military doctrine that distinctly differentiates between the state and the faction, and between soldiering and ideological affiliation—whether in thought, appearance, or field practice.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية