The Security System in Syria: The legacy of the former regime versus the Idlib model

Syria is entering a major phase of security transformation following Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) rise to power in late 2024. The former security apparatuses, known for their extensive control and role in suppressing the opposition, have been dismantled. Despite talk of security reforms under the new government, there are concerns about the re-emergence of a centralized security authority that prioritizes regime protection at the expense of citizens’ rights, especially in light of weak oversight and the lack of genuine integration of all military factions inside Syria into the country’s new General Security Agency.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – May 19, 2025

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

The Syrian security system entered a new operational and organizational phase when opposition factions, led by HTS, rose to power in December 2024. This shift occurred after decades of reliance by the former Syrian regime on a strong and expansive security apparatus that helped consolidate the control of the Ba’ath Party and the dominance of the Assad family over the state. During the crisis that erupted in 2011, the apparatus played a pivotal role—primarily by suppressing demonstrations, protests, and pursuing dissidents—in ensuring the regime’s cohesion and survival throughout a decade of conflict.

Accordingly, this paper aims to provide a brief overview of the Syrian security forces and intelligence agencies, their organizational structure, main personnel, and operational methods before the 2011 crisis, as well as the current state of the security apparatus under the new government. Additionally, it seeks to explore various perspectives on restructuring the security institution and its future role.

The Security System Under the Former Regime

The security system under the former regime consisted of four main departments intertwined with one other and complexly linked to Ba’ath Party, with the chain of command ultimately leading to the head of the regime as the supreme commander of the army and armed forces. These four directorates (referred to as shu’abs or divisions) were: General Intelligence (state security), Political Security, Military Intelligence, and Air Force Intelligence. Each operated with structural independence, had its own leadership, and oversaw dozens of units and branches spread across the country. Each was also distinct in its scope of responsibilities and institutional affiliation, with some reporting to the Ministry of Defense, others to the Ministry of Interior, and some to the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. Nonetheless, all directorate operations were coordinated and overseen by the National Security Bureau (NSB), which the Ba’ath Party established in 1966.

After the 2011 crisis, the Syrian government established the Central Crisis Management Cell, which became known as the “Crisis Cell,” to coordinate the government’s response to the Syrian Civil War and suppressing dissent. Later, the National Security Office, created in 2009 and activated after the bombing of a meeting of Crisis Cell officials in 2012, replaced the National Security Bureau and reported directly to the president.

Most of these agencies were established after the coup led by the Ba’ath Party in 1963. The party relied on the security apparatus as the foundation for consolidating its rule. These agencies were granted broad powers backed by constitutional and legal provisions, primarily under an emergency decree issued in March 1963. Other decrees included the 1964 “Protection of the Revolution” Decree No. 6, the 1965 Ba’ath System Decree No. 4, the 1969 establishment of the State Security Directorate Decree No. 14, and the 1981 Law for the Establishment of Economic Security Courts. These laws imposed severe and extensive penalties, up to and including the death, for criticizing, resisting, or opposing the revolution’s objectives, whether through speech, action, or writing.

Some decrees went even further by protecting the leaders and members of the security agencies, granting them immunity from legal prosecution for their actions. For instance, the 1969 decree regulating the General Intelligence Directorate’s operations (No. 5409) prohibits prosecuting its employees for crimes committed while performing their duties. Similarly, the 1969 decree establishing the State Security Directorate (No. 14) includes a provision that prevents the prosecution of its staff for illegal actions committed in the line of duty.

Moreover, Decree No. 64 of 2008 expanded the prohibition on prosecuting personnel in the Internal Security, Political Security Division, and Customs without the approval of their superiors. In practice, this legal framework enabled the security apparatus to go beyond the written law, introducing extrajudicial punishments such as enforced disappearance or travel bans. It also granted the security system an increasingly dominant role in legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the government—and in the daily lives and affairs of citizens.

In reality, a significant part of the 2011 crisis and the protests against the regime can be traced back to the problematic relationship between Syrian citizens and the state security apparatus. The responsibilities of these agencies extended to monitoring internal affairs, particularly those of regime opponents. For example, the Military Intelligence Directorate (primarily tasked with monitoring military personnel) and the Air Force Intelligence Directorate (responsible for protecting airspace and the president’s security) expanded their activities to include gathering intelligence on civilians and the suppression of dissidents. Moreover, Military Intelligence oversaw several paramilitary units, which broadened its influence beyond the traditional functions of military intelligence.

In addition, both the General Intelligence and the Political Security directorates were designed to monitor political activities, opposition groups, and various aspects of public life. These agencies have been widely accused of committing serious human rights violations, both before and after the 2011 Syrian crisis. For instance, they played a role in 1982 Hama massacre. Following the outbreak of the crisis, a 2011 report by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry under the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, described the violations committed by security forces and the army as “crimes against humanity.” In 2013, the UN Security Council unanimously condemned the “widespread human rights violations” perpetrated by the security forces.

The New Government’s Security System

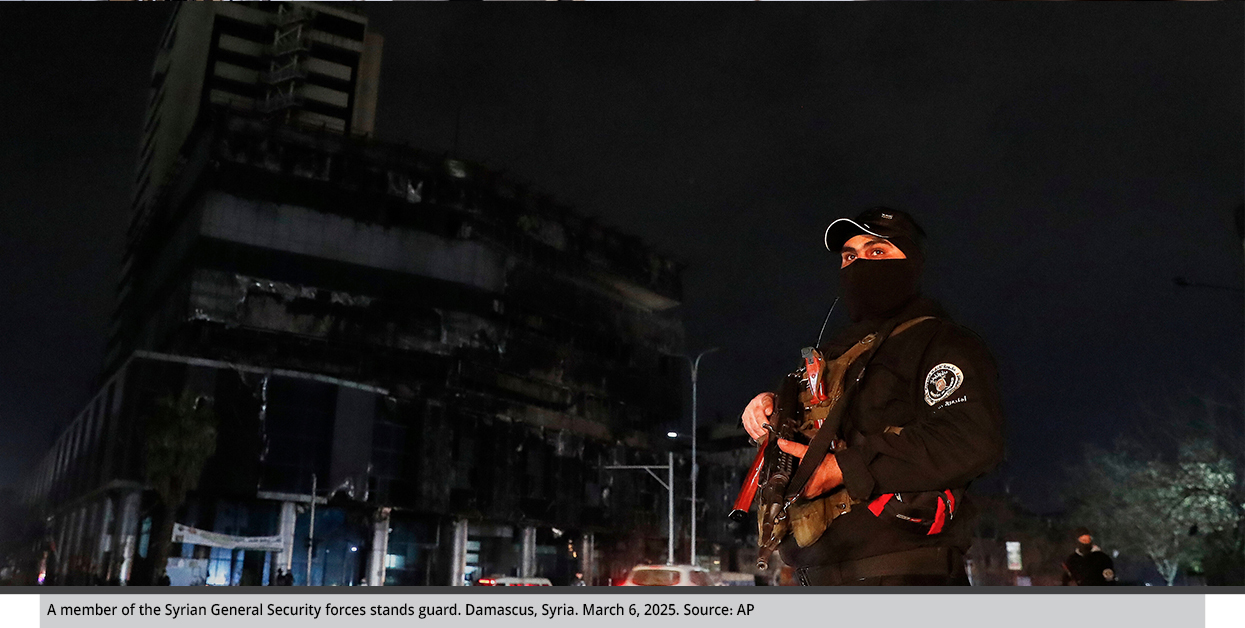

The HTS-led takeover of power by opposition armed factions marked a fundamental shift in the country’s security and military structure, particularly after the new government announced the dissolution of the former regime’s army and security agencies on January 29, 2025. This represented a complete break from the previous security establishment and brought a new security model to the forefront dominated by units affiliated with HTS: the General Security Directorate (GSD).

HTS appointed its own leaders to head the new security agencies. Among the most prominent appointments was Anas Khattab (AKA “Abu Ahmad Hudud”), who was named head of the Syrian General Intelligence Service (GIS). Following the announcement of the transitional government on March 30, 2025, Khattab became the minister of Interior. He was succeeded as head of the GIS in early May by Hussein al-Salama (AKA “Abu Musab al-Shuhail”). Meanwhile, the newly established General Security Directorate is led by Abdul Qader Tahhan (AKA “Abu Bilal Quds”).

In general, the new GSD is built upon the apparatus previously established in Idlib, which had served as a powerful tool in the hands of HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Julani, now known as Ahmad al-Sharaa, the president of Syria. Elite units affiliated with HTS are currently responsible for securing the capital, Damascus, and the area surrounding the presidential palace, in addition to maintaining control over the group’s stronghold in Idlib province.

In practice, the Interior Ministry announced a work plan that includes promises of extensive reforms that will help modernize prisons, combat drugs, improve traffic systems, and advance criminal investigations. Interior Minister Khattab also moved to unify the leadership of the police and General Security forces across all governorates under the supervision of a single official and under a centralized security authority.

Theoretically, the new government operates the same way it did during its control of Idlib. The GSD holds greater importance in safeguarding the new government than the newly formed Syrian army. The HTS and its leaders maintain control over the security forces, while the Ministry of Defense’s forces consist of a broad spectrum of armed factions.

Previously, security operations in Idlib were independent from the Ministry of Interior, which was then affiliated with the Syrian Salvation Government HTS formed in 2017. The focus was placed more on security-related tasks, such as surveillance and intelligence, rather than conventional policing. A notable example illustrating this broad, centralized approach to security is the 2023 espionage case that led to the arrest of hundreds of HTS members and military commanders under the pretext of infiltration by the international coalition. This incident highlights the comprehensive nature of the security apparatus’s work, its direct subordination to President al-Sharaa, and the extent to which he relies on it to consolidate his power.

Practically, the attempt to merge the two agencies under a single authority may lead to the dominance of a security mindset at the expense of policing functions, posing risks to public freedoms. There is a fundamental difference between the culture of General Security, which is rooted in secrecy and the use of informants, and that of the police, which is based on public service, protecting civilians, and community engagement.

While the General Security model in Idlib demonstrated effectiveness and efficiency within a relatively limited environment, it failed to build a relationship of trust within the community. Instead, it leaned more toward protecting the interests of HTS than those of the public. Its record is marked by a legacy of abuses, including arbitrary arrests, torture, raids, and suppression of protests. Sources indicate that the security apparatus in Idlib operates prisons and detention centers outside the official framework of its Salvation Government.

These practices led to waves of protests in parts of Idlib, which eventually resulted in the GSD being placed under the supervision of the Interior Ministry in March 2024. However, it continued to maintain both its actual independence and direct link to the president.

Risks and Concerns of Expanding the Idlib Security Model Across All of Syria

1- The generalization of the General Security model from Idlib—centralized decision-making, direct subordination to the president, and weak institutional oversight—across all of Syria poses the risk of reproducing an authoritarian security apparatus. This model prioritizes regime security over societal security and lacks transparency and accountability, much like the system that existed under the former regime.

2- The security apparatus in Idlib was developed within a relatively homogeneous social environment. Extending this model to highly diverse regions, such as the coast, Damascus, Suwayda, and Homs, without incorporating local personnel poses significant risks. Chief among these is the loss of trust among various social components in the security apparatus and the potential for fueling tensions and divisions. These risks are heightened by the agency’s involvement in the events along the coast in March 2025, and in Suwayda and the towns of Jaramana and Sahnaya in the Damascus countryside in early May 2025.

3- Rapidly expanding the General Security apparatus into new governorates by quickly recruiting inadequately trained personnel and granting them high ranks without prior military or police experience will undermine the efficiency of the security agency and increase the likelihood of human rights violations and widespread security chaos.

4- The situation in Syria does not require the absolute strength of the security apparatus, but rather its effectiveness in enforcing the law, combined with a commitment to transparency and respect for rights. Achieving this demands a radical transformation in the philosophy of Syrian security, shifting it from a tool of repression to one of citizen protection. This transformation would clearly define the powers, limits, and oversight mechanisms of security agencies within a transparent legal and constitutional framework, which would be supported by international assistance to prevent state collapse or external forces taking control of its security institutions.

Without such reforms, Syria will remain trapped between the chaos of security vacuums and the tyranny of repressive agencies. Therefore, expanding the Idlib security model across Syria without first making appropriate structural and procedural changes, especially amid sectarian and ethnic tensions, poses grave risks. Chief among these are the reproduction of an authoritarian security state, the escalation of local conflicts, and the threat to the country’s territorial integrity and unity.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية