The Potential of the Chinese-Russian Military Alliance and Its Impact on the Indo-Pacific Security Landscape

Strategic Assessment | This assessment focuses on the relationship between Russia and China, specifically examining their military alliance. It highlights their joint military drills conducted in the East China Sea near Japan in 2022. These drills reflect Beijing and Moscow’s shared strategic vision and recognition that reshaping the international system necessitates exerting control over the Western Pacific region.

by Anas Al Qasas

- Release Date – Feb 19, 2023

The Ukrainian crisis that erupted in February last year marked a major turning point in the international system and the scale of the roles of its main actors. This crisis came at a time when countries were seeking to mitigate the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic and began to gradually shape the future of the international system.

Despite what the course of the crisis may suggest, Russia is attempting, in one way or another, to avoid the direct and indirect burdensome cost of its operations in Ukraine in terms of economy, international trade, and its standing in the politics of world powers.

Russia’s desire to control Ukraine coincided with China’s desire to break the blockade imposed by the United States and its allies on Beijing in the Pacific, especially as Japan doubled its military spending to meet the NATO standard, which poses a common threat to both Beijing and Moscow.

This comes within the framework of a common strategic understanding and realization by China and Russia that changing the rules of the international system can only be achieved by imposing control over the Western Pacific, from the cold waters in the Sea of Okhotsk to the warm waters in the South China Sea.

Expanding Strategic Competition in the Western Pacific

As soon as the Ukraine crisis started, a strategic rivalry in the Western Pacific expanded northward, reaching the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea.

In the fourth week of December 2022, the Russian and Chinese armies carried out a joint live-ammunition drill in the East China Sea off the coast of Japan. The exercise involved the most significant naval units of the Russian Pacific Fleet and an extensive presence of Chinese navy fleet along with the participation of the air forces of the two armies.

According to the final statement broadcast by the Russian news agency TASS, the naval drill included some sophisticated exercises to target the submarines of opposing forces in the region amid a tight interaction between Chinese and Russian forces. In a video released by the Russian Ministry of Defense, some Russian naval soldiers aboard the Russian battleships were shown speaking in Chinese to their Chinese counterparts.

A Related Context of Intensive Competition

At the end of November, a few weeks before this naval drill, six Russian TU-95 and two Chinese Xian H-6 strategic bombers conducted joint sorties over the East China Sea toward the Sea of Japan. The Russian strategic bombers were “followed by fighters from foreign countries” during parts of that flight, according to a Russian statement issued on the air drill.

This mystery posed by the Russian statement was answered by Zvezda, the Russian state-owned television network, which noted that the Russian TU-95 bombers were soon accompanied by two Japanese F-15 and F-35 aircrafts, U.S. Air Force F-22 stealth fighters, and U.S. Navy F-18 Super Hornet fighters and an Boeing EA-18g Growler interceptor. In addition, the South Korean army confirmed that it sent fighter jets when the Chinese and Russian bombers entered South Korean airspace.

With clear and swift responses from the United States, Japan, and South Korea, the Sino-Russian bombers turned back toward the East China Sea through the Miyako Strait and then headed toward China escorted by two Chinese Shenyang J-16 multirole strike fighters over the East China Sea. This was confirmed by Chinese state media with news footage about the patrol that noted the Chinese J-16s were refueled in the air by a Chinese Y-20 refueling aircraft.

The footage, along with images released by Japan, indicated that the J-16s were from the 7th Fighter Aviation Division in Jiaxing; the Chinese bombers were from the 10th Bomber Division located in Anking in the eastern province of Wuhan; and the Russian bombers belonged to the 182nd Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment stationed at Ukraine, the largest nuclear bomber base in Far East Russia.

Were They Ordinary Drills?

The Russian and Chinese narratives about the naval drill, which took place in the fourth week of December, were that they were “ordinary” and followed cooperation protocols dating back to 2012. Such a narrative lacked contextual consistency. For instance, it is noteworthy that such drills never before had been conducted with live ammunition.

Moreover, the Sino-Russian naval drill off the Sea of Japan occurred a few days after Japan announced it would raise its military budget 60 percent over the next five years—from 1 percent of national GDP to 2 percent by 2027—to meet NATO standards. Japan needs to counter China’s growing influence in the Pacific and the development of North Korea’s missile capabilities, in accordance to Japan’s new National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy approved by its parliament in mid-December.

Similarly, these joint air drills of Chinese and Russian strategic bombers came just 24 hours before the United States announced launching its new strategic bomber, the B-21 Raider, which observers expect will be one of the most prominent American tools in consolidating the rules of the current international order for decades to come.

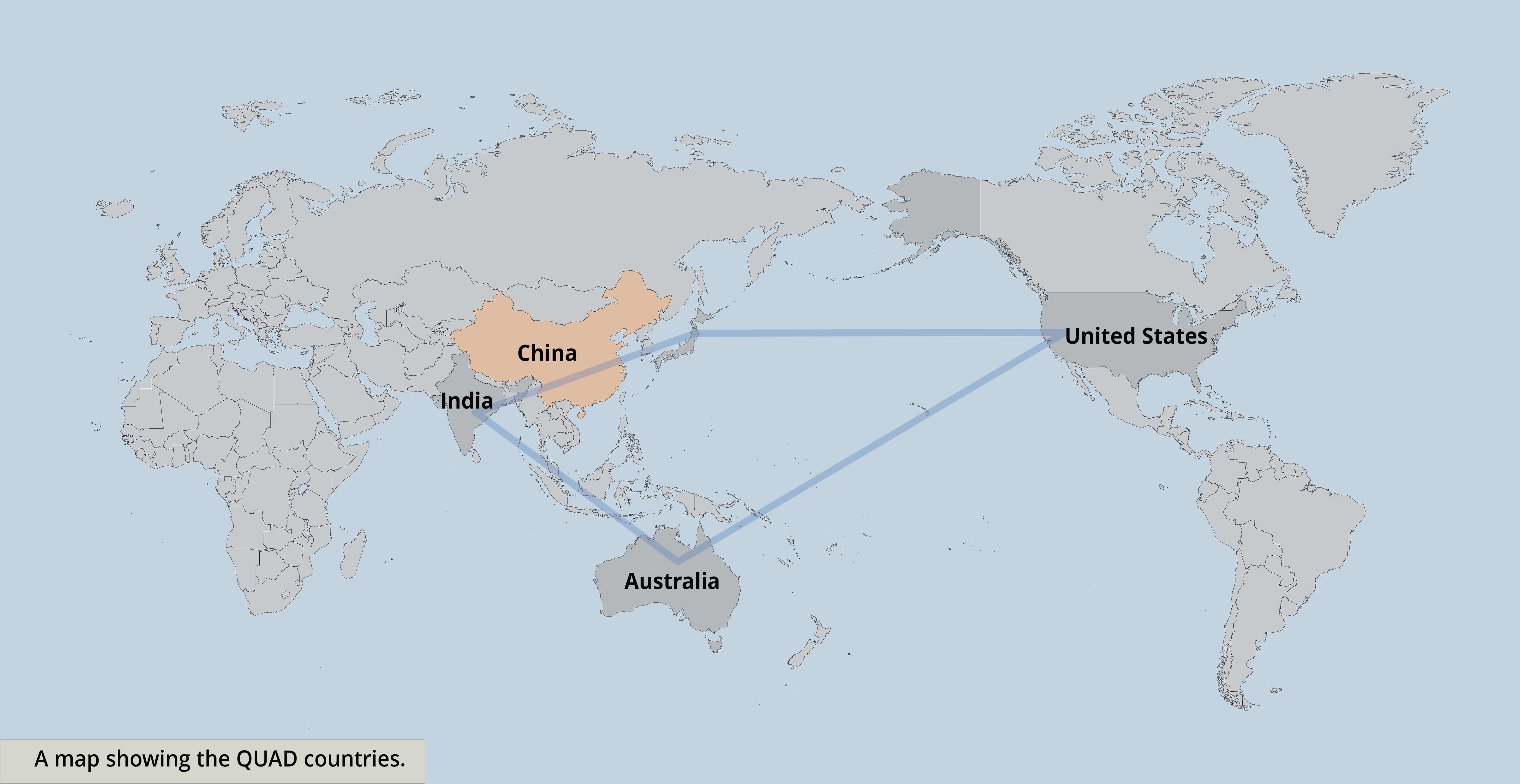

However, this joint maneuver with strategic bombers was not the first of a kind. In May 2022, coinciding with the Quad Leaders’ Tokyo Summit (United States, Japan, India, and Australia), a joint Sino-Russian air drill began over the waters of the Sea of Japan using the same models of weaponry and following the same paths.

Therefore, the official narratives promoted by China and Russia that these drills were routine may not be accurate. The most appropriate interpretative framework for what is taking place is understanding the context of the military, political, and security dynamics in the Western and North Pacific over the past months.

Broader Context of Strategic Cooperation

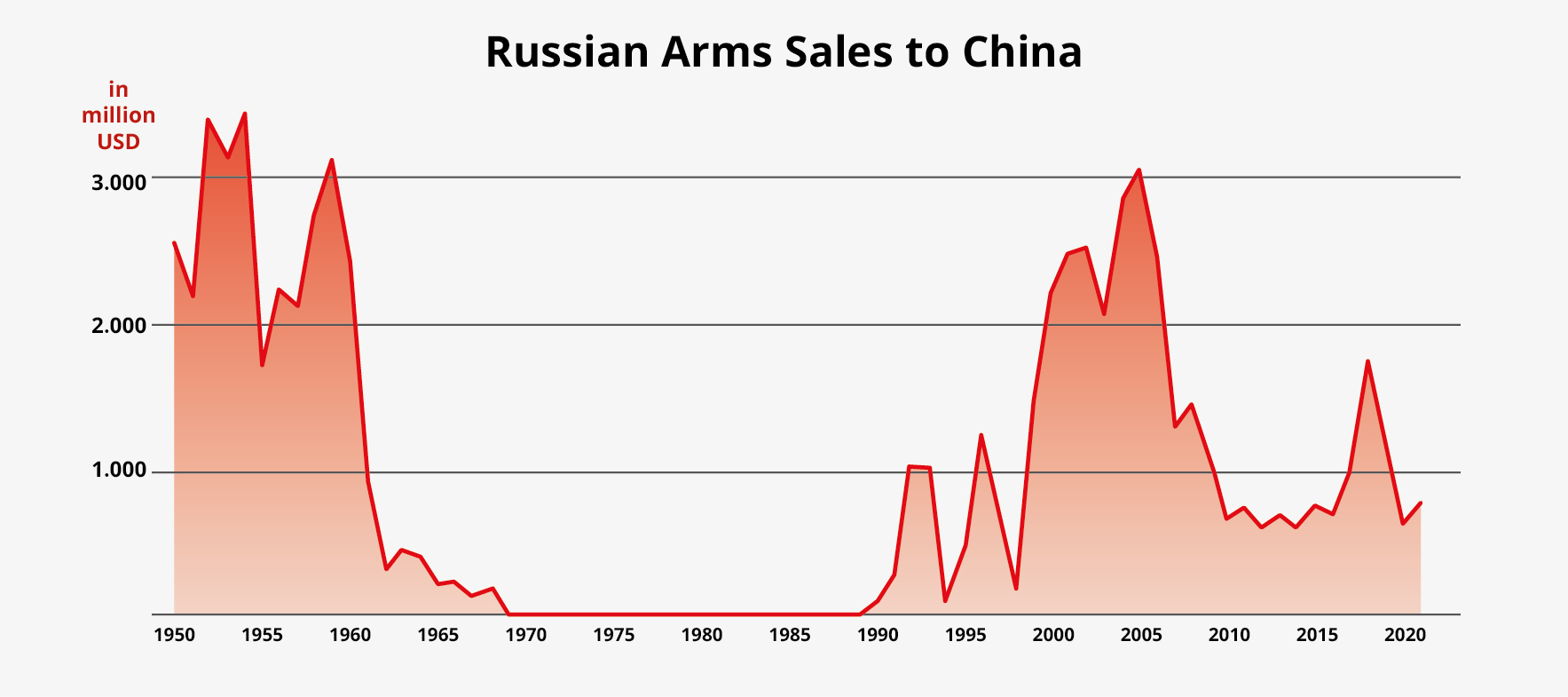

Along with the huge shifts in the relationship between Russia and the West, caused in part by the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, Sino-Russian cooperation began to increase, especially on defense and military issues. After Vladimir Putin became president of the Russia Federation in 2000, Russian arms sales to China tripled within five years.

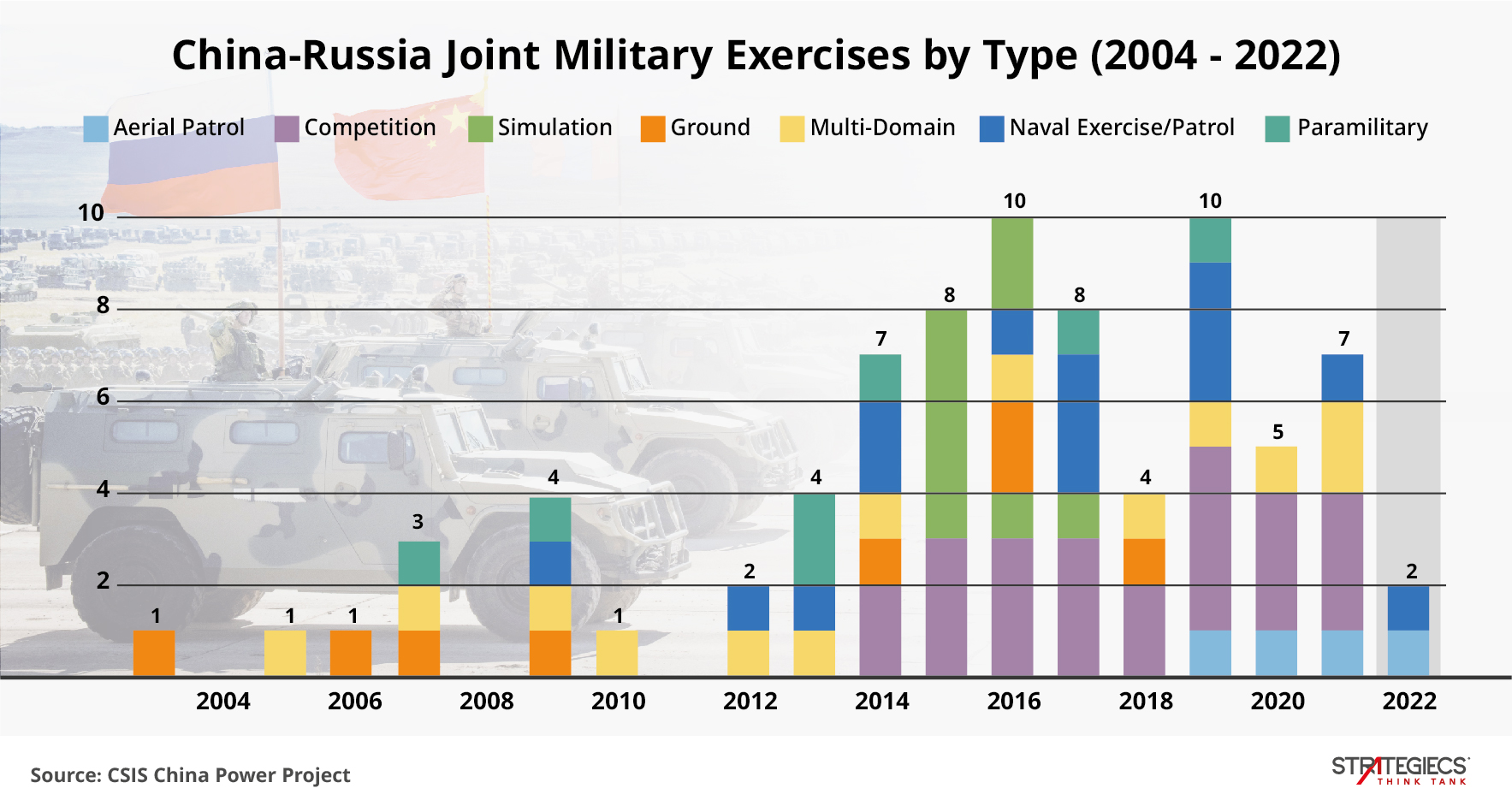

The number of joint Sino-Russian drills has also increased from three before 2008 to 10 since 2016, according to the Washington, DC-based Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Chinese Power Project.

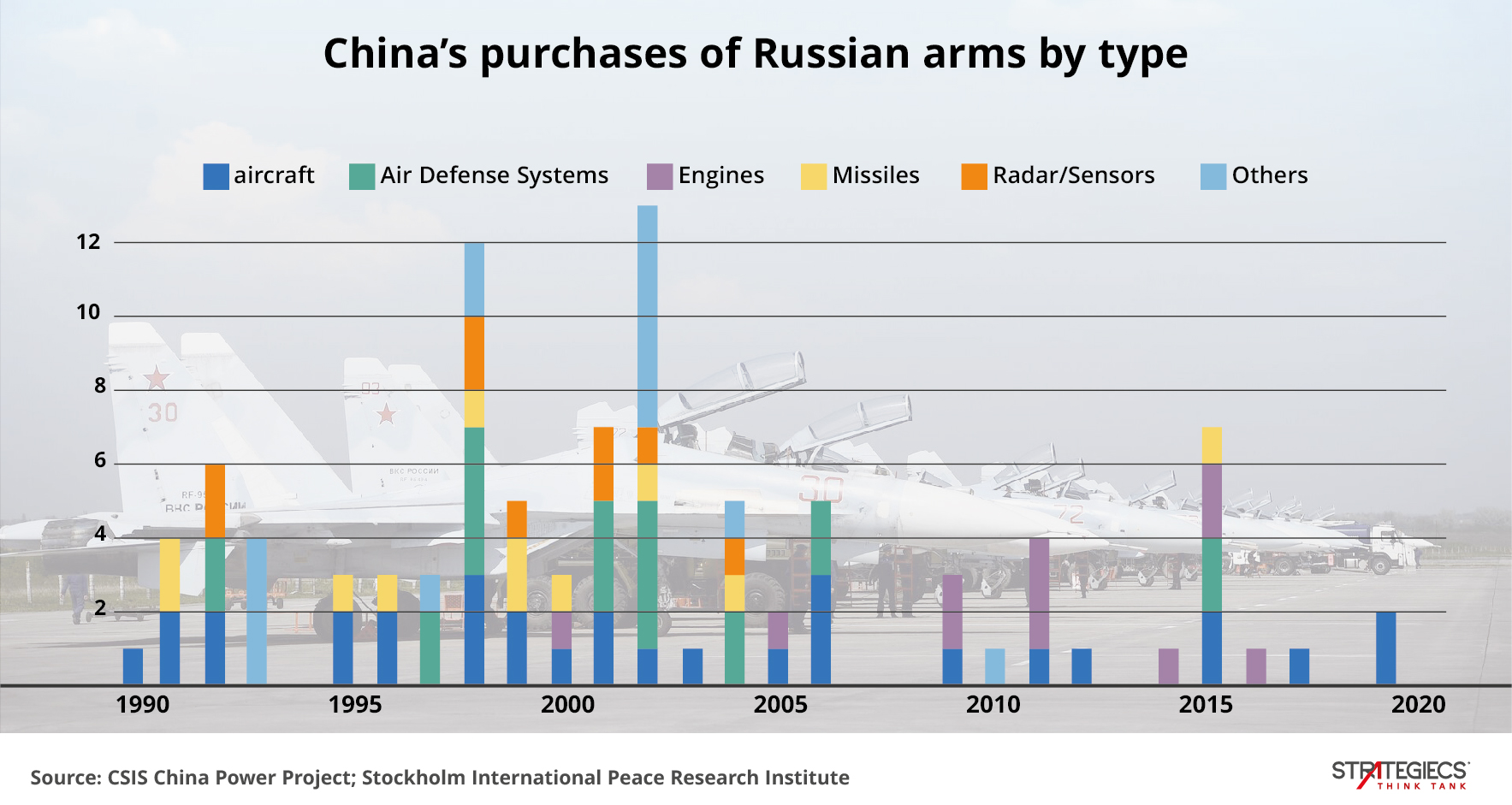

While Russian arms purchases have decreased with China’s technological boom in the same period, Chinese orders for Russian engines (aviation, naval, and missile battalions) have doubled, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Chinese orders for Russian aircraft engines have nearly quadrupled in the past decade, according to statistics from the Stockholm Institute.

This increase in the purchase of engines occurred simultaneously with the transfer of knowledge and experience. According to data announced by the Russian authorities and espionage cases, the Center for International and Strategic Studies’ Chinese Power Project noticed the absence of Chinese espionage attempts on ordinary Russian technologies, limiting espionage attempts to gain revolutionary technologies that Moscow will not easily give away. Out of the four Chinese espionage cases disclosed in 2021 and 2022, for instance, there were only three cases in which spies leaked to Beijing sensitive information about hypersonic missile technologies.

Are Sino-Russian Activities Changing the Security Situation in the Pacific?

To obtain a precise answer to this question, we should carefully scrutinize the Russia objective in deploying in the Pacific, despite the sensitive timing for Moscow. If we consider that Moscow’s main goal at this time is to change the rules of the international system, according to its the declared rhetoric and current behavior, there will be no better shortcut than to change the security situation in the Western Pacific to turn the rules of the international system upside down.

The territorial seas of the Western Pacific, from the Sea of Japan to the South China Sea, are crossed by about 65 percent of international trade. Since an international tribunal in a landmark ruling dismissed Beijing’s claim to much of the South China Sea, Beijing began to strictly and clearly express its intentions regarding its territorial oceans. Nevertheless, the biggest changes in the region occurred last year with the implementation of the Quad Strategic Dialogue outcomes, forming what can be considered an Asian NATO aimed to encircle China from all its maritime sides, from Japan in the north to Australia in the south and India in the west.

Therefore, China is in dire need of the Russian Navy, which still enjoys a significant presence in the seas, especially since the escalation of the Japanese threat is an important variable and common danger for both countries.

Complex Russian Considerations and an Unforgotten History

Though the current regional situation in the Pacific Northwest is becoming increasingly problematic for Moscow, the Russian considerations are very complicated with regard to this region. Most of the Russian Navy is located in the western strategic direction, with the Barents, Baltic, and Black seas. Given the changing strategic situation in Europe, a European-focused Russia is unlikely to reduce its military presence in the continent at all costs, even if the NATO blockade necessitates reinforcing the nuclear triad in Kaliningrad, Murmansk, and Belarus.

Since it is difficult to talk about the creation of a new Russian naval fleet due to the severe financial and strategic crisis Russia is experiencing, if Russia restructures its naval fleets in favor of strengthening the Pacific fleet, the Russian port in Vladivostok is frozen most days of the year—a logistical crisis—and the Russians will eventually be forced to cooperate with China.

What applies to the Russian naval fleet also applies to its strategic bombers. Russia will probably not withdraw strategic bombers from the eastern strategic direction under any circumstances, as this is a declaration of defeat and withdrawal from its raging battle with NATO.

A true naval alliance between China and Russia will not be limited to the symbolic presence of the Russian navy. Rather, it will require major troops that are permanently prepared and highly trained on the Indo-Pacific region, unlike how it is required in the cold seas of Europe.

This potential alliance faces problems beyond arms shortages. Chief among them is a mutual lack of trust. Strategic planners in both countries know the history regarding the growing Japanese power and American support of it. There is also a history of stories of mistrust between Moscow and Beijing, which both suffered the pain of disagreements dating back to the beginning of the Chinese state itself, especially with the death of Stalin and the rise of Khrushchev. There was then an interruption of relations for nearly a quarter of a century before the start of the U.S.-China strategic dialogue in the early seventies.

This long story of mutual suspicion that continues to this day makes the alliance very problematic. It is made more problematic by regional choices that harshly clash with the national security of any of them, especially with regard to the Russian-Indian alliance, the Chinese policies in the Central Asian region that seek the upper hand over Russia, the current position on Afghanistan, the Collective Security Treaty, and much more.

The Northwest Pacific Regional Order and the New World Order

New features for the Indo-Pacific region began to take shape by the end of 2022 when Australia and Japan increased their military spending as part of broader alliances with the United States in a strategic context that includes the Indo-Pacific.

Japan’s increased military spending was faced by measured Chinese and Russian reactions that were often later subject to replication and escalation. However, Japan’s doubling of its military spending calls for an intensive effort by China to double its naval capabilities, which is impossible at this time since China is already reaching record levels of warship production, a status that can only be lifted in the event of an emergency declaration.

At the moment, no one is closer to China than Russia in sharing its fears and hopes of changing the rules of the international system. But, as observed by U.S. National Security Agency Cybersecurity Director Rob Joyce, “Russia is like a hurricane … loud, aggressive and it is the near-term threat right now … but China is climate change, they are the long-term pacing threat for us.”

This makes Russian not likely to be the best choice to support China in anticipating the increasingly complex Pacific security situation. Russia’s current circumstances related to the Ukrainian crisis, its lack of weapons, and its loss of strategic orientation constitute an increasing burden for any party trying to solve its problem with Russian help.

Therefore, the relations between Beijing and Moscow are likely to continue as they are now, timely dealing with any crisis in the Western Pacific.

* The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author. Strategiecs shall bear no responsibility for the views and/or opinion of its author on security, economic, social, and other issues, as they do not necessarily represent the views of the Think Tank.

Anas Al Qasas

Expert on strategic and international affairs, war and peace issues

العربية

العربية