Scenarios of the State and the System of Government in Post-Assad Syria

The spotlight and numerous analyses focus on the future of Syria and its system of government after the downfall of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Several questions are raised about the country’s political and social future, the shape of the coming Syria, and the form of its system of government. There is also speculation on how politics could be recycled to move away from internal power struggles and external interventions. Despite regional and international consensus on the need to establish stability in Syria, the risks associated with the transitional process could lead to various repercussions, particularly concerning tactical agreements between Syria’s armed and political forces.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – Dec 19, 2024

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

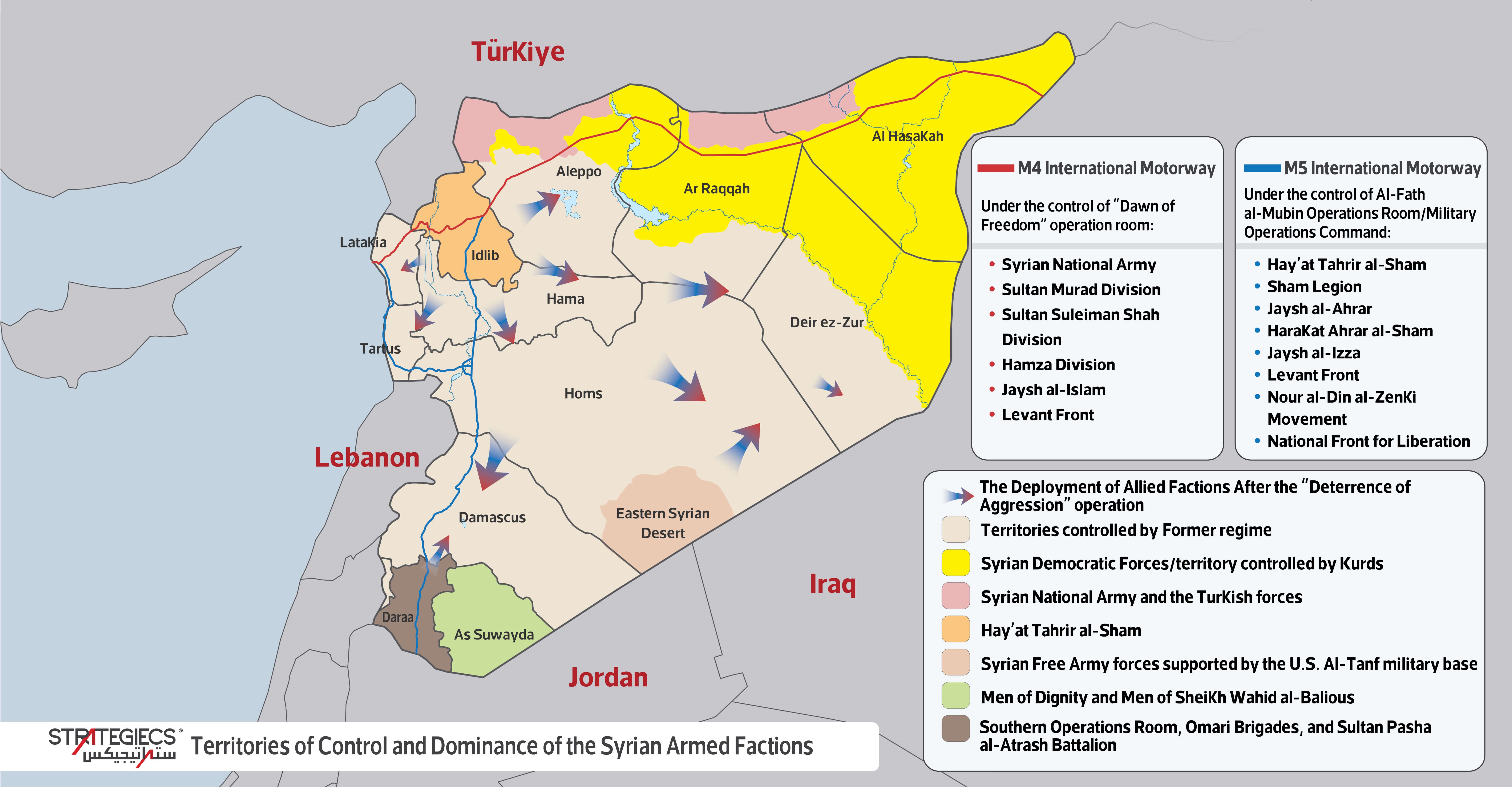

Syria enters a transitional phase amid a state of uncertainty, following the armed opposition’s capture of the capital, Damascus, on December 8, 2024, and the toppling of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. This rapid development came after a coalition of Syrian opposition groups called the Command of Military Operations (CMO) launched an operation called Deterrence of Aggression on November 27 that was led by the Fath al-Mubeen Operations Room based in Idlib. During this operation, the opposition forces gradually seized Syria’s major cities, including those along the international M5 highway.

The Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a Sunni Islamist political and paramilitary organization, announced the establishment of a transitional period to be led by a caretaker government headed by former Assad regime Prime Minister Mohammad Ghazi al-Jalali. This government is tasked with managing Syrian administrations and institutions, effectively bringing to a close six decades of Ba’ath Party rule, a quarter-century of Assad’s leadership, and more than a decade of ongoing crisis that has gripped the country since 2011.

In light of the multiple local Syrian actors, the wide variation of their directions and backgrounds, the demands of Syrian citizens both at home and abroad, and how the politics can be recycled away from the internal conflict for power and the foreign interventions, these developments raise many questions about Syria’s future political and social structure, as well as its system of government.

Future Demands for the Upcoming Syria

The spotlight and numerous analyses are focused on Syria’s future and its system of government after the fall of the Assad regime, in what might be considered a relatively peaceful transition of power compared to the intensity of internal conflict and the multiplicity of actors in the Syrian crisis since 2011. On one hand, the country has maintained the continuity of its institutions, while on the other hand, the events have excluded two of the most significant players in the country: Russia and Iran, along with a number of factions and armed militias, most notably Hezbollah.

The news of a regime change theoretically met the aspirations of the Syrian people, who had been governed by a regime widely classified as “highly authoritarian,“ accused of marginalizing the majority of the population, and viewing both Islamic and liberal ideologies with hostility. Furthermore, it has disregarded the rights of non-Arab minorities, such as the ban on the Kurdish language in circulation and print in 2019, reinforcing a previous decision to prohibit its use in state institutions in 1986.

Nevertheless, Syria’s future is not limited to local political affairs alone, nor can it be confined to the aftermath of the regime’s collapse and the initial consensus among social components to achieve that goal. The success of the “day after” Bashar is more closely tied to a set of requirements and considerations that must be taken into account in light of the transitional phase and what it will eventually establish. Among the most important of these considerations are:

First: International consensus

All countries in the region and around the world have sought to promote the idea that the process of Operation Deterrence of Aggression should be considered a domestic and internal matter. Many countries, except for Turkey and the United States, had limited themselves to merely observing the transformations within the country. However, when the situation became clearer after HTS took control over Damascus, countries increased their direct and indirect involvement in Syrian affairs.

They began to outline their demands and requirements from the country’s transitional administration and to assess the future of their relations with it. This is evident in the diplomatic visits by international officials to Damascus and the security meetings held in the Jordanian city of Aqaba, where a consensus was reached to support an inclusive political process.Thus, Syria’s future cannot be separated from international considerations, particularly in three main approaches: foreign military presence on Syrian soil, the need for international consensus on reconstruction, and the need to lift international sanctions on the former regime and the transitional government.

In terms of military presence, Turkish and American forces are heavily deployed in vital and strategic areas of the country. The U.S. military, along with Kurdish forces, controls roughly a third of Syria’s territory in the northeast, stretching from the northeastern part along the Euphrates River to the southeastern area near the al-Tanf border crossing. This region houses the U.S. military base that secures the border triangle between Syria, Jordan, and Iraq. It also contains the majority of Syria’s oil, agricultural, and water resources.

Meanwhile, the Turkish army is deployed in the Syrian provinces of Idlib, Aleppo, Raqqa, and Hasakah, providing logistic and military support to the CMO and Operation Dawn of Freedom in its fight against the former regime and, currently, against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Russia, for its part, maintains two naval bases along Syria’s coast, namely in Tartus and Hmeimim.

Thus, the presence of foreign forces on Syrian soil keeps these countries actively engaged in the political scene, especially since the three countries—the United States, Turkey, and Russia—support three distinct components of Syrian society. The U.S. forces back the Kurds, Turkish forces support Sunni Islamist groups, and Russian forces operate predominantly in areas with an Alawite majority. These three powers are likely to compete, both in terms of political and military representation for their respective supporters in the future government, or may even push for autonomous governance, similar to the Kurdish autonomy in Iraq for Washington or the Libyan-style scenario of Khalifa Haftar’s forces for Russia.

As for the need for the international community in the reconstruction process, the estimated cost of rebuilding Syria is between $200 billion and $300 billion, distributed across various cities and governorates. For example, the estimated number of destroyed buildings is 36,000 in Aleppo, 35,000 in Eastern Ghouta, 13,000 in Homs, 12,000 in Raqqa, and 64,000 in Hama. In reality, it is unlikely that Syria can carry out reconstruction independently without broad international and Arab assistance.

This places the future of the political process at the center of a wide range of international demands from Arab, European, or American sides to participate in funding the reconstruction. This situation could prioritize certain issues over others according to the demands of the donor countries, exposing the entire process to risks of conflicting interests. For instance, countries like Germany, France, and Sweden focus on supporting minorities, particularly the Kurds, while countries like Turkey and Russia oppose granting the Kurds more political or geographical advantages.

The influence of these countries extends to other areas beyond reconstruction, specifically regarding sanctions imposed on the former regime or on HTS and its leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa (Abu Mohammad al-Jolani). In the United States, these include the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 and the 2022 CAPTAGON Act, as well as the State Department’s designation of al-Sharaa as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” in May 2013. Additionally, in 2017 the U.S. government offered a reward of $10 million for information leading to al-Sharaa’s capture. Its decision to drop the reward for al-Sharaa’s arrest in December 2024 remains an effective tool for Washington to set its demands on the CMO’s future agenda.

Second: Controlling the Weapons by the State

One of the key requirements of the transitional phase and the most important indicators of its success is the controlling of weapons by legitimate, state-run institutions. The presence of armed groups is widespread across Syria, and the nature of this spread varies depending on the group holding the weapons, the regions of their deployment, and their objectives.

Firstly, the Operations Room of al-Fath al-Mubeen (which became known as the Command of Military Operation after the regime change) controls most of Syria’s major cities along the M5 international highway. Meanwhile, the Dawn of Freedom Operations Room spans the M4 international highway, with the Kurdish-led SDF also deployed in areas intersecting with Dawn of Freedom. Both operations rooms (CMO and Dawn of Freedom) comprise a wide range of factions and armed groups.

In the first room, HTS (formerly the al-Nusra Front) is the largest faction, partnered with Ahrar al-Sham, Sham Legion, Jaysh al-Izza, Levant Front, Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, and factions of the National Front for Liberation. In the second room, there is an alliance of factions that were united by Turkey in 2017, including the Syrian National Army, formed from groups that were once part of the Free Syrian Army, as well as the Sultan Murad Division, Sultan Suleiman Shah Division, Hamza Division, Jaysh al-Islam, and factions of the Levant Front.

On the other hand, the country faces a vertical spread of weapons, with ethnic minorities on one side and ideological factions on the other. For instance, the Kurds possess Syrian Democratic Forces, while the Druze community in Sweida has seen the establishment of several factions, including the Men of Dignity Movement and Men of Sheikh Wahid al-Balious. These factions have been tasked with protecting their community from the regime’s forces and defending protesters.

Additionally, there is a horizontal spread of weapons across the Syrian geography. While most opposition factions are present throughout the country, they are divided by their origins and geographic areas of influence. In the north, there is HTS, the Syrian National Army, and factions like Jaysh al-Islam and others, with a significant portion of these groups being local to the region (including Aleppo, Hama, and Idlib). In the south, factions like the Southern Operations Room, the Omari Brigades, and the Sultan Pasha al-Atrash Battalion were formed by officers who defected from the Syrian regular army. In the west, the U.S.-supported Syrian Free Army forces operate in the Syrian Desert near the Iraqi-Syrian border. In the east, the Kurdish-led SDF are deployed.

Therefore, ensuring that weapons are controlled exclusively by the state is considered a fundamental priority for the next phase, given the proliferation of armed Syrian groups and factions and the state of chaos and political vacuum that followed the collapse of the regime. This requires, as a basic step, the surrender of weapons to the army or to a military council after its formation, with the integration of some fighters from these factions into the national army after they are properly trained.

One of the key factors in maintaining stability during the transitional process is preserving the structural integrity of the army, even if its leadership is changed, while also strengthening the capacity of state security agencies to ensure public safety. In reality, this is one of the most complex requirements, especially with the diversity and multiplicity of armed factions and their differing goals and objectives, which could lead to the risk of fragmentation or internal conflicts in search of greater gains. These factions have previously engaged in armed confrontations, including the conflict between HTS and other factions affiliated with the Free Syrian Army in 2017.

Third: Centralization of Power

Before the Deterrence of Aggression operation, Syria was divided between three authorities: the regime and the government in Damascus, the Salvation Government in the areas controlled by HTS in Idlib, and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria led by the Syrian Democratic Council in the northeastern part of the country. After the collapse of the Assad regime, Mohammad al-Bashir, the head of the Salvation Government, became the head of a transitional government until early March. This meant that the country was now under two governing authorities. The first, the interim government, controlled most of Syria’s geography, while the second retained its administration in the areas of Hasakah, Raqqa, and the outskirts of Deir ez-Zor after withdrawing from Aleppo following the Dawn of Freedom operation launched by the Syrian National Army.

On the other hand, the centralization of political power is neither official nor structural across the entire country. Many minority areas are governed by local authorities led by tribal sheikhs and elders. A prominent example of this is the Druze situation in the Suwayda governorate, which, largely driven by the Druze community’s elders and leaders, remained a center of protests against the previous regime. This situation could serve as a future model for the coastal areas of Syria that have a significant Alawite presence.

Despite the fact that the “Deterrence of Aggression” factions entered Syria’s coastal areas and religious leaders of the Alawite community distanced themselves from Assad, the signs of instability remain. One of the key concerns is that most military leaders and militia commanders moved to the coast after the regime’s collapse. There are also latent fears among the Alawites about their future, particularly due to their historical association with the former regime.

Thus, Syria’s future hinges on the ability of the transitional government to unify the country under a single central authority. This requires careful monitoring of the diversity of forces guiding the transitional phase and how to involve all national components and different societal factions, both within Syria and abroad, in the political process. Otherwise, as long as HTS seeks to monopolize decision-making and representation for a specific sect, ideology, or region, the risks of conflict will rise, potentially leading to scenarios of federalism, division, or chaos.

Fourth: Transitional Administration

Syria today faces a complex situation on multiple fronts. Politically, the country is experiencing a political vacuum with the absence of central authority and leadership, which poses a central challenge following the overthrow of Assad’s regime. This is coupled with fears of the country slipping into chaos if the post-regime phase is not managed in an organized, consensual manner based on a comprehensive and inclusive transitional mechanism and a unified national vision that ensures the preservation and continued operation of state institutions and their ability to fulfill their service functions without collapsing. This is especially crucial given that these institutions were structurally dependent on the previously ruling Ba’ath Party.

With the fall of the regime and the ensuing political instability, concerns arise regarding the potential for power struggles between opposition political and military forces. This fear is exacerbated by previous experiences in which the collapse of government led to internal conflicts, especially after the collapse of state institutions and the disintegration of key bodies such as the military and security agencies, resulting in chaos and the absence of the rule of law. Notable examples of this include Iraq after 2003 and Libya following the Arab Spring events.

Therefore, the upcoming phase requires a Syrian national consensus based on a unified vision to manage the phase in a harmonious manner until the new changes take place. This will enable the state to establish a government (or a council) and transitional institutions capable of maintaining security and stability in order to prepare the country for a democratic political transition. The failure to manage the transitional phase could lead to prolonged chaos, especially if the roots of the Syrian crisis are not addressed and justice for all is not achieved. This requires the factions and organizations to have the ability to reach a political consensus on a unified vision to manage the transitional phase with stability, especially given their differing ideological orientations and regional interests.

On the other hand, the transitional phase of the political system requires both internal and external support (international and regional) to form a transitional council that includes representatives from all parties without the dominance of any ethnic or religious component in order to achieve a national and representative consensus.

However, this requires them to recognize the need to build a central authority without the interference of supporting parties in internal matters to serve their strategic interests, which may not align with respecting Syria’s sovereignty over its territory. This also requires the formation of representative bodies that include various entities with political and social diversity, enjoying international and popular support while ensuring the independence of these bodies from external interference or attempts at partisan control. Only then can they be responsible for leading the phase towards stability, drafting a new constitution, and preparing for free and democratic elections.

Transitional bodies are also considered essential organizational tools for the transitional phase, including the formation of a transitional government with clear powers and fair representation that brings together various Syrian components. This will help avoid the risk of the phase slipping into new local conflicts. Furthermore, it involves drafting a new constitution based on a national consensus regarding its foundations, one that meets the aspirations of the Syrian people and aligns with the necessary changes in the political system to create and protect the democracy they seek.

However, it is important to note that the weakness in the structuring of transitional bodies and institutions can obstruct the process and limit their ability to manage state institutions and oversee public services, ultimately hindering progress toward a successful political transition. This was evident in the Libyan experience, where the absence of such bodies and their roles led to a state of chaos. In contrast, Tunisia succeeded in creating bodies capable of managing presidential elections effectively.

Fifth: Achieving Social Integration

The next phase requires achieving social integration that strengthens national unity and restores the social fabric, which has been fragmented during the years of the Syrian crisis. This is crucial to ensuring the country’s stability, especially given the diversity of cultures and identities resulting from internal displacement and refugees fleeing to multiple countries. This situation has created a cultural and social divergence among Syrians, as millions of them have been exposed to different living and cultural conditions both within Syria and abroad. Additionally, the geographic distribution of Syrians in host countries with diverse cultures and social systems has led to differences in customs, traditions, political views, social norms, and economic perspectives.

On one hand, the 2011 crisis introduced a new social dimension characterized by the non-homogeneous cultural pluralism of the Syrian people. This pluralism is transnational, not simply a local cultural diversity. For instance, the populations in northeastern Syria, including the displaced people, have interacted with a culture closer to the Turkish one. The Turkish lira was used as the circulating currency, Turkish humanitarian organizations managed the distribution of aid, and Turkish educational systems and language intertwined with the local population in those areas.

On the other hand, many refugees live under difficult conditions in camps both within Syria and abroad. A new generation of Syrians has emerged in these camps with limited exposure to urban life and none of the necessary skills and resources to be prepared for the job market or to contribute to post-conflict reconstruction. In contrast, a segment of Syrians in advanced industrialized countries have acquired valuable skills and embraced liberal Western culture. These individuals will certainly make significant contributions to Syria’s future and reconstruction.

However, their return is contingent upon maintaining a cultural and financial level comparable to the places where they currently reside. Many of them hold positions in international organizations or work with Western governments, and some have networks of international economic relations that could be leveraged in Syria’s reconstruction. Therefore, these individuals may have the capacity to contribute to reconstruction plans, institutional reforms, and state governance through international institutions, provided if these individuals receive local political and popular support.

The return of approximately 10 million refugees to their homeland is considered a fundamental condition for rebuilding Syria on a comprehensive and sustainable basis. However, this requires a stable and secure environment. The return of refugees is linked to all the aforementioned requirements and should be a primary priority in the upcoming phase. This necessitates reconstruction efforts and the creation of appropriate living, security, economic, and service conditions, along with providing returning refugees with security and legal guarantees.

The participation of refugees and expatriates in establishing the country’s social and economic future and in rebuilding its social fabric is crucial. They represent an important economic and human resource for reconstruction, improving living conditions, developing investments, and achieving sustainable development. There are also refugees in Arab countries with low incomes whose return requires employment programs, rebuilding infrastructure in devastated areas, and providing economic aid. This requires international consensus on supporting them through civil society institutions, stimulating the economic situation, and encouraging investment through reconstruction programs to enhance unity and solidarity among different segments of society.

Scenarios of the System of Government in Syria

The future of Syria appears open to several scenarios, all of which are tied to a series of challenges, actors, and requirements. The interaction of these factors will shape the future model and form of the political system in the country. These scenarios can be summarized as follows:

Scenario 1: The Taliban Style System of Government in Afghanistan

This scenario assumes that HTS, which was originally founded on a “jihadi-Salafi” ideology when it was known as “Jabhat al-Nusra,” might follow a system of government similar to the one implemented by the Taliban in Afghanistan. There are parallels between the contexts of control and the ideological characteristics of both cases. In 2021, the Taliban rapidly advanced across Afghanistan, managing to take over the entire country within a month, ultimately reaching Kabul and seizing power. Afterward, they declared the establishment of an Islamic Emirate led by the movement. This trajectory was accompanied by reconciliation and coordination with the United States, which withdrew its forces in parallel with the Taliban’s advance into the capital.

For Syria, the situation seems to be moving in a direction of similar understandings between the U.S. and Turkey with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham. Washington, for instance, preferred to hold the previous Syrian regime accountable for the “deterrence of aggression” operation, while warning Iraq and Iran against intervening in Syria’s internal affairs. On the other hand, Turkey has shown clear support for HTS and its leadership. Ankara seems to favor working with an Islamic government in its vicinity, one that aligns with its positions, particularly on national security matters such as the Kurdish issue.

Notably, Qatar has also played a role in recent developments, following the visit of Qatar’s State Security Service Chairman Khalfan al-Kaabi to Damascus on December 15. This visit coincided with the presence of Turkish intelligence chief Ibrahim Kalin in Syria, and it came just hours after U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Ankara and Doha as part of a regional tour that also included Jordan. The meetings between the two sides with the leader of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, Ahmad al-Sharaa, and the interim government’s Prime Minister Mohamed al-Bashir were focused on discussing the future of the country in the coming phase. These visits marked the first official international diplomatic visits to Syria following the regime change.

This scenario becomes stronger as HTS moves towards shaping the country’s future independently and centrally. This could result in HTS leader Ahmad al-Sharaa becoming the future president of Syria, and the group’s members forming the core of the future Syrian military. A system of government would be established based on Sharia law, with Islamic-oriented forces assuming control and drafting a constitution reflecting Islamic values, focusing on implementing justice and equality from an Islamic perspective. This would require the group to assert control over minority areas, particularly Alawite regions and Kurdish-controlled areas.

Scenario 2: The Model of the System Government in Iraq

This model assumes the formation of two governments in Syria: one, the central government in Damascus, and the other, the Self-Administration of the Kurds in the northeast. The first would be responsible for defense, foreign policy, and finance, while the second would be responsible for managing the areas controlled by the Kurds in Syria, which, like Iraq, would control most of the country’s oil and gas resources.

In light of this scenario, it is likely that the Kurds would maintain their armed forces, similar to the Peshmerga, and that they would be integrated into the future Syrian army, as SDF Commander-in-Chief Mazlum Abdi has requested. This is reinforced by the U.S. stance on preventing the expansion of the Dawn of Freedom operations into Kurdish-controlled areas in Raqqa and Al-Hasakah, where U.S. forces are stationed. On December 11, 2024, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III announced working with Kurdish forces to confront Turkish-backed factions. However, this faces a challenge from Turkey, the main supporter of HTS and the fighting factions in the Dawn of Freedom operations room.

It is likely that countries such as Iran and Iraq will view the entrenchment of Kurdish self-rule as a risk, but it has the approval of the United States, Israel, and possibly Russia.

In this scenario, the future system of government in Syria would be federal, achieving a balance between the Damascus government and the Kurdish region. It would include both local and federal elections. This model allows for the division of the country into regions with a degree of autonomy, providing powers for managing their own affairs while maintaining the authority of the central government to handle sovereign matters. This ensures the participation of minorities in the management of their geographical areas, reducing internal conflicts between them, respecting ethnic particularities, and preserving the geographical unity of Syria.

Scenario 3: The Security Confederal Model

This scenario assumes that the system of government in Syria will move towards dividing the country on geographical, security, sectarian, and ethnic bases. There is still uncertainty among minorities, including Alawites, Druze, and Kurds, regarding the direction set by the Islamic forces controlling the scene. Each of these minorities has its own armed factions. In addition, Alawite officers and leaders from the previous regime have launched a widespread rebellion against the transitional authority to disrupt its progress and intensify the security and political challenges it faces.

For instance, an ambush by armed individuals loyal to the previous regime resulted in the death of 15 members of the Sham Legion in Latakia, the stronghold of the Alawites. The first counterattack by fighters of the previous regime since its collapse, it points to possible plans for future attacks. This means that HTS faces serious challenges in implementing a centralized government across Syria, which, if achieved, would remain vulnerable to exhausting and costly security incidents.

Underscoring this scenario is the geographical distribution of minorities being supported by external powers. While Turkey supports the transitional government led by Islamists, the United States backs the Kurdish self-administration in the northeast. Meanwhile, Russia, Iran, Hezbollah, and Iraq support the Alawites and remnants of the previous regime. As for Israel, it seeks to establish communication channels with the Druze community in Syria. Israeli media reported demands from the Druze elders in Hader, a village in southern Syria, to annex them to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

According to Israeli military spokesperson Avichay Adraee, on December 11, Shlomi Binder, the head of Israeli military intelligence, met Sheikh Muwafaq Tarif, the spiritual leader of the Druze community in Israel, at a time when the Israeli military was conducting air and naval strikes to destroy the Syrian army’s heavy weapons and unilaterally annexing the occupied Golan Heights, including Mount Hermon, in defiance of international law.

Scenario 4: The Model of a Civil Democratic State

This scenario assumes the success of the transitional authority in establishing a civil democratic system of government with a comprehensive national army, strong institutions, and a representative electoral system that considers the negatives of sectarian power distribution, as seen in Iraq and Lebanon. Some statements made by leaders of HTS and the transitional government suggest a future vision for a civilian state and its political system, relying on the Syrian national identity rather than existing sectarian identities. The relationship between the state and the people would be based solely on citizenship, without discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, sect, or denomination. The political identity of the state would be citizenship, and the source of legislation would be positive laws within a centralized administrative structure that ensures the separation of powers, effective state institutions, and integration with civil society organizations that rely on efficiency to achieve development, social justice, and peaceful coexistence for all.

Based on this, many countries have changed their positions towards the transitional authority, despite its leader being listed as a terrorist by the United States. Washington has not ruled out removing this designation. Blinken announced direct communication with the group, while European countries, such as Germany and France, are waiting for the transitional authority’s stance on minority rights and representation.

Conclusion

In reality, the U.S. pressure tools—economic sanctions and its military presence in Syria—along with Syria’s need for European and Arab investment and funds for reconstruction and development, compel the transitional authority to take into account the demands of these countries when establishing the future system of government. This is especially true since the return of refugees could remain another form of pressure on the authority, either by preventing the return of skilled individuals or pushing them to return, thus increasing the population and economic burdens on the new authority.

Finally, these scenarios for the future of the Syrian political system and its possible forms require a sustained state of stability, which is considered a complex and major challenge for the transitional government. The management of the upcoming landscape is marked by numerous sensitivities that could, at any moment, push the country into a state of chaos, power vacuum, and geographical, ethnic, and sectarian division.

Despite the regional and international consensus on the necessity of establishing stability in Syria, the risks associated with the transitional process may result in several consequences and warnings, especially regarding the tactical agreements between the Syrian armed and political forces, which have not yet reached the level of strategic integration in terms of vision, goal, and entity. As noted in a 2018 article by Hasan Ismaik, chairman of the Board of Trustees of STRATEGIECS Institute, any negotiated peace agreement would at best serve as a temporary bandage over an unstable ceasefire, and it is likely to remain so until the scars and perceived grievances begin to fade. Therefore, the main obstacle to peace is figuring out how to rebuild the collective civil rhetoric.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية