Trump’s Plan: Second Phase Scenarios

With the launch of the second phase negotiations of U.S. President Donald Trump’s plan to achieve a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, the two-year war is entering a new stage that may bring about unexpected developments. While attention is focused on the major issues on the negotiating table, it seems that the fine details within the more complex files may prove decisive in shaping a new reality on the ground—and perhaps a political and security reality that does not align either with current expectations or the declared terms of the plan.

by AbdulMalik Amer and Dr. Reyad Shreem

- Release Date – Oct 29, 2025

On October 14, 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the launch of the second phase of his comprehensive plan to achieve a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip and establish long-term peace between Israelis and Palestinians. Earlier, both Israel and Hamas had approved the U.S. proposal known as the Trump Plan, which went into effect on October 10, followed by the implementation of the first phase on October 13, which included a ceasefire and the release of detainees.

Despite the approval of Israel and Hamas, the implementation of most of the first phase as well as the start of negotiations for the second phase, which covers the plan’s more complex issues, give the negotiation framework a set of scenarios that could lead either to broad understandings, upcoming confrontations, or a prolonged stalemate on the ground.

The Context of the Second Phase of Negotiations

The announcement of the launch of the second phase of negotiations on the Trump Plan came after both parties had partially implemented the first phase, which included Hamas and other Palestinian factions handing over the Israeli detainees who were still alive, as well as the human remains of several Israelis in the Gaza Strip.

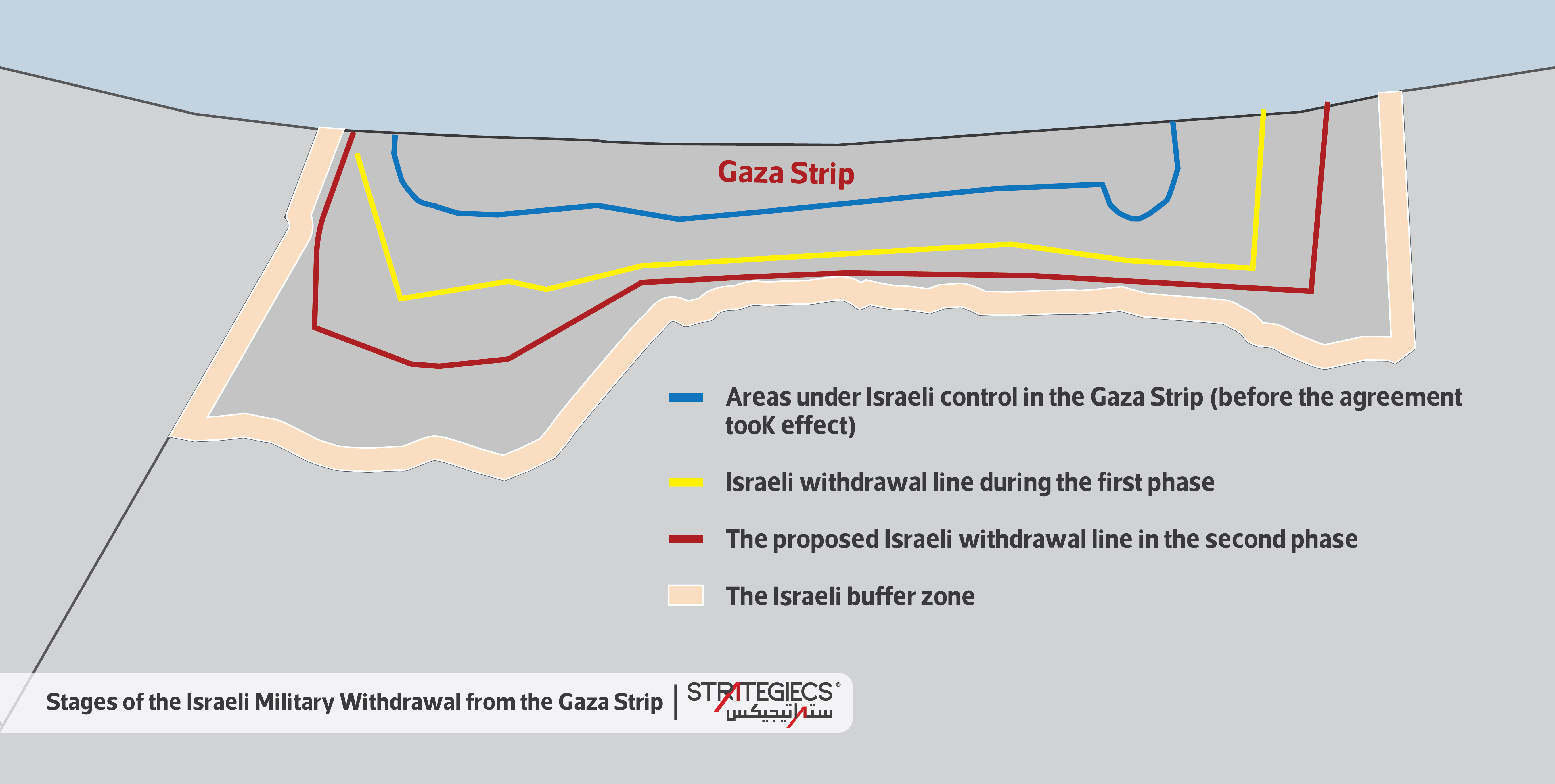

Meanwhile, in accordance with the plan, the Israeli army withdrew to the Yellow Line—the first withdrawal line extending from Beit Hanoun in northern Gaza, through Beit Lahia, Gaza City in the center, Al-Bureij, and Deir al-Balah, and down to Khan Younis in the south of the Strip—while maintaining its deployment in certain areas of Rafah, Beit Hanoun, and along the Philadelphi Corridor.

However, the implementation of the first phase faced a challenge known as the “bodies crisis.” Israel asserted that the success of the second phase—or even the continuation of negotiations—depended on Hamas handing over all the remains of Israeli soldiers and civilians, estimated at 28 bodies, of which only nine had been delivered. This comes amid Israel’s skepticism toward public statements by Hamas leaders in Gaza that they do not know the whereabouts of the remaining bodies and that they needed technical teams and heavy machinery to locate them.

Given that pressure from the United States contributed to overcoming this obstacle and moving on to the second phase, it means that the issue of the bodies has become tied to the broader discussions of this phase, particularly with the acknowledgment of the need for international teams and specialized equipment to recover them.

This implies that Israel will maintain a role within the areas inside the Yellow Line, both in intelligence and operational terms, while keeping constant pressure on Hamas throughout the second phase. On the other hand, this sensitive issue affects other equally complex matters, such as establishing a multinational force, disarming the Gaza Strip, and forming an interim governing body. This comes amid clear differences reflected in the statements made by American, Israeli, and Palestinian parties—specifically Fatah and Hamas.

Complexities of the Negotiation Framework and the Stance of Its Parties

As the second phase of negotiations begins alongside the “bodies crisis,” which Israel swiftly used to slow down the transition to this phase, other gaps have also emerged. Some stem from the complexity of the issues to be negotiated, while others have been deliberately engineered by parties involved in the negotiation process.

For instance, although Washington shares Tel Aviv’s goals regarding the war, it has been exerting pressure to prevent both its possible renewal and any Israeli actions that could alter the current status quo. For this reason, American officials have been making continuous and overlapping visits to Tel Aviv. On October 23, Vice President J.D. Vance concluded his visit to Israel as Secretary of State Marco Rubio arrived the same day. Earlier, on October 20, U.S. envoys Steven Witkoff and Jared Kushner arrived in Israel and stayed for three days.

These urgent visits by high-ranking American officials underscore that Washington has become both a guarantor of the agreement and a direct actor in the developments taking place in the Gaza Strip.

On Israel’s side, the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) established on October 10 an international civil-military headquarters in the Kiryat Gat area in southern Israel, comprising approximately 200 American service members with expertise in transportation, planning, security, logistics, and engineering along with representatives from partner nations, non-governmental organizations, international institutions, and the private sector. Israel negatively views this as a form of direct oversight of its actions and decisions—potentially even a mechanism for restraining Israeli military actions.

On Hamas’s side, Washington has been directly warning it of the consequences of any violations. For the first time since the outbreak of the war, CENTCOM, under the command of Admiral Brad Cooper, communicated directly with Hamas, demanding strict adherence to the Trump Plan and an immediate halt to violence against civilians in the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile, Trump himself publicly threatened military action against Hamas if it continues its acts of violence.

This development suggests that the United States is providing security assurances to Israel while simultaneously preventing it from taking any unilateral actions that might disrupt the negotiations. It also highlights the growing constraints imposed upon Hamas, as the current situation appears to be managed within a framework that transcends the historical boundaries of its conflict with Israel.

For Israel, the intensive U.S. involvement may help achieve some of its objectives—but not necessarily in a form that fully aligns with its preferences. The gaps in implementing the plan’s provisions have already become evident. While the United States views Türkiye as a partner in the peace process—and potentially as part of the multinational force—Israel rejects this notion. Israeli Foreign Affairs Minister Gideon Sa’ar explicitly announced this rejection on October 27. Notably, Israel had previously barred a Turkish rescue team from entering the Gaza Strip on October 16.

Divergences between the United States and Israel are also evident in their prioritization of key issues. Teel Aviv links the handover of weapons to the start of reconstruction efforts, the deployment of international forces, and its full military withdrawal from the Strip. Washington, however, favors having international forces oversee the disarmament process while simultaneously initiating the reconstruction plan.

Furthermore, there is a difference in how Israel and the United States assess violations and breaches of the ceasefire. While Israel considers Hamas’s delay in handing over the bodies of the dead as a violation of its obligations under the agreement, the United States does not share this view.

On October 19, Israel accused Hamas of opening fire and responded with a series of airstrikes, while Trump noted that the attack had been carried out by a rogue faction within the movement and was not ordered by Hamas leadership. On October 28, the United States intervened again to prevent escalation after Israel resumed airstrikes on the Gaza Strip, accusing Hamas of attacking Israeli forces stationed east of the Yellow Line.

As for Hamas, its response to the Trump Plan, which reflects its stance on the issues of the second phase, has also created gaps in how it engages with the plan’s provisions. Hamas’s positions remain ambiguous and unclear regarding the handover of its weapons, as reflected in statements by its officials. Among these, Mohammad Nazzal, the leader of the Hamas political wing, told Reuters that the movement intends to maintain security control in Gaza during an interim period, while its chief negotiator, Khalil al-Hayya, stated that Hamas’s weapons will not be handed over until after the establishment of the Palestinian state—even though the explicit establishment of a Palestinian state is not included in the plan’s provisions.

On the other hand, Hamas has referred the issues of governance and administration of Gaza after the war to the broader Palestinian officialdom, including the Palestinian Authority (PA), in a move aimed at distributing responsibility among all Palestinian forces, including the PA and Fatah, the largest faction within the Palestinian Liberation Organization. At the same time, however, it has created new obstacles, foremost among them the difficulty of achieving such a national consensus. This challenge became evident when Fatah boycotted the Palestinian faction meetings in Cairo, limiting participation to the Palestinian Authority’s representation.

Moreover, what was agreed upon in Cairo—such as forming a temporary Palestinian committee of independents to manage the affairs of the Gaza Strip and affirming in a statement that “security in Gaza is the responsibility of the official Palestinian security agencies, and any international force should be at the borders, not inside the Strip”—constitutes highly contentious issues in themselves, for several reasons.

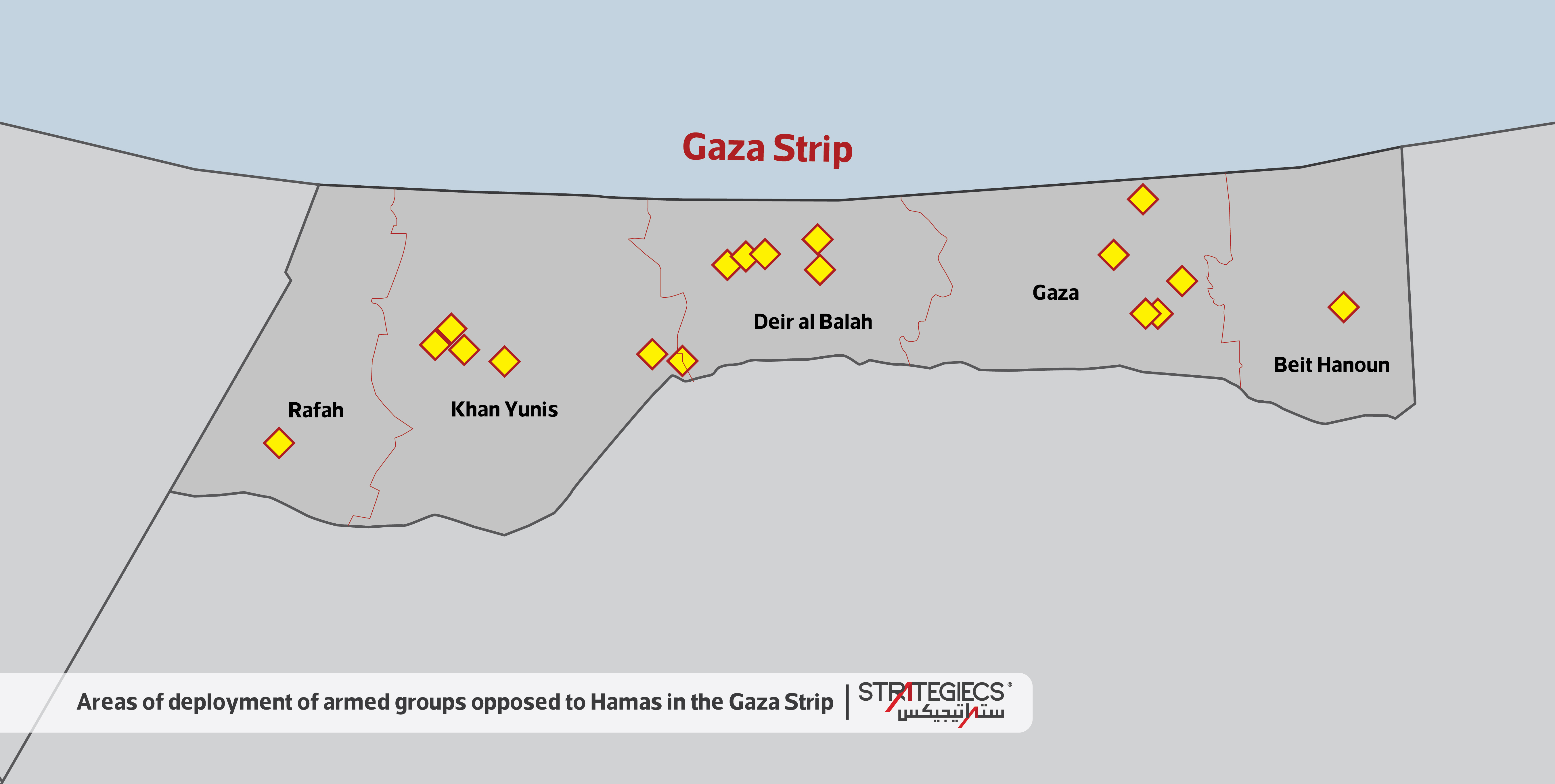

First, they represent points of disagreement between Hamas and the other Palestinian factions. They may also reflect Hamas’s attempts to prevent anti-Hamas armed groups in Gaza—such as those led by Yasser Abu Shabab (Popular Forces), Ashraf Al-Mansi (People’s Army Northern Forces), Rami Halis (a group that operates in defiance of Hamas authority in areas under Israeli control), and Hossam Al-Astal (Counter-Terrorism Strike Force)—from gaining popular or tribal legitimacy. These groups are seeking to exploit the decline in Hamas’s influence to expand their own roles and areas of control.

Second, Israel rejects any presence of forces loyal to the Palestinian Authority or any attempt to unify the West Bank and Gaza under a single administration. Israel appears to prefer Hamas to remain weak and exhausted, engaged in conflict with anti-Hamas factions rather than allowing the negotiations to reach a stage where the Palestinian discourse becomes unified under a comprehensive national administration.

Scenarios for the Second Phase of Negotiations

In reality, it appears that the three main parties—Israel, the United States, and Hamas—along with the Palestinian Authority, are moving along independent and parallel paths that may neither intersect nor align. This applies particularly to their overall visions regarding the more detailed issues, placing the fate of the second phase of negotiations before a set of possible scenarios.

Scenario One: Overcoming the Obstacles of the Second Phase

Overcoming the obstacles of the second phase begins with progress in negotiations, which so far have appeared slow or altogether stalled, while the United States maintains its stance against violating the agreement or returning to war, successfully managing violations in three instances to date.

However, given the clear differences in interpreting the agreement’s provisions and each party’s expectations for what lies ahead, engaging in negotiations does not automatically mean overcoming these obstacles. While Israel insists on the disarmament of the factions, Hamas’s actions against armed groups reveal its intent to retain influence and control over its weapons—at least in the areas from which the Israeli army has withdrawn.

On the other hand, the first phase has highlighted the field-level complexity of the “bodies crisis” and will likely reveal broader complications in the future, especially concerning issues such as reconstruction itself, the prioritization of areas either beyond or before the Yellow Line, and the complexities of the transitional authority’s mandate in a geography occupied by multiple actors.

This geography intertwines ideology, tribal structures, criminal organizations, and armed groups amid a population on the brink of unrest due to the collapse of the basic foundations of contemporary life and its full dependence on aid. It is within this same environment that international forces will operate, making it potentially hostile or too unstable to guarantee their safety.

All of this highlights the actual complexity on the ground in implementing the Trump Plan. Israel and Hamas, aware of this, have been preparing their respective positions on the ground, anticipating either the plan’s stumbling or its potential stalemate.

Scenario Two: Entering a Long-Term Non-Consensus Negotiation Framework

Direct U.S. intervention and its continuous pressure on the parties to the agreement have been the main factors maintaining its cohesion so far. Since the immediate goal is to advance the second phase of negotiations and prevent a return to war, this means that the negotiation framework is likely being protected by American will—not necessarily ensuring its success, but guaranteeing its stability.

During this second phase, major issues and fine details are addressed, and achieving agreement between the warring parties requires a long-term negotiation framework similar to other Israeli-Palestinian negotiations since 1993 that stalled despite changes on the ground. This hypothesis is strengthened when considering the interests, objectives, and constraints of the three main parties.

For Hamas, such a stalemate could allow it to maintain its influence and weapons within the Yellow Line and focus its military efforts against groups and tribes opposed to it. This contrasts with the potential outcome of progress in negotiations, which could signify the actual end of the movement’s military structure.

This scenario may align indirectly with three of Israel’s long-term goals. For instance, allowing Hamas to retain controlled influence and limited power in Gaza blocks the PA’s attempts to unify the West Bank and Gaza under its administration in the future; undermines international efforts to recognize a Palestinian state without direct Israeli intervention; and allows Israel to retain control over large areas of Gaza in line with its declared vision for the post-war period.

For the United States, the primary goal is a ceasefire in Gaza, as the future of the Strip is considered only a small part of its broader regional peace plan. Therefore, a stalemate in negotiations—without a return to war—may not be a significant issue for Washington. It aligns with its conceptual approach to peace elsewhere, such as between Russia and Ukraine, which it frames as a ceasefire that preserves the current geography of control until a formal ceasefire is declared.

Scenario Three: Collapse of Negotiations and Return to War

The collapse of negotiations is unlikely in the near term, given the U.S. insistence on maintaining its cohesion. However, the possibility of a return to war increases under certain circumstances, such as Hamas or splinter groups rejecting the agreement, carrying out repeated attacks or a major strike against Israeli forces beyond the Yellow Line, or Israel responding with disproportionate military force, potentially resetting the conflict back to its original state. In fact, Israel has already acted in this manner three times, in ways deemed disproportionate by the United States, indicating that Israel’s desire to return to war remains strongly present.

Moreover, the likelihood of renewed conflict rises over the medium and long term, particularly if Scenario Two occurs. A prolonged stalemate could lead either party to attempt to alter the ground realities where negotiations stalled. While Hamas’s immediate goal is to neutralize rival groups and maintain its authority and influence, in the future it may decide to expand its objectives to include Israel’s full withdrawal from the Gaza Strip.

This could involve carrying out attacks individually or through groups on Israeli forces beyond the Yellow Line, or through splinter factions from Hamas and other Palestinian factions pursuing similar goals. Such actions are plausible in post-conflict environments. Likewise, repeated attacks or increasing threats to Israeli forces could prompt Israel to resume war or launch a new, more precise military campaign against Hamas in the areas under its control within the Yellow Line.

AbdulMalik Amer and Dr. Reyad Shreem

Specialized Senior Researchers

العربية

العربية