Foreign Fighters File in Syria: Between Entitlement and Risk

This paper addresses the complex situation of the foreign fighter file in Syria following the change of the former regime. It details their composition, explores the long-term challenges and risks arising from their integration into the new Syrian army, their leadership roles, and the implications of this both locally and internationally. It also touches on the issue of thousands of foreign fighters from ISIS who are currently detained. Lastly, the paper reviews future scenarios for these fighters, whether those integrated into the new state structures or the ISIS detainees held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – May 29, 2025

This opinion article is part of the series: Syria.. Transformations, Variables, and the Future of the State of Uncertainty

The security and military aspects in Syria witnessed a radical transformation after the regime change in December 2024. One of the key features of this shift was the integration of foreign fighters who had joined armed opposition forces in local combat against the former regime into the security structures of the new authority. This development sparked a range of multifaceted local and international reactions of concern over the regional and global security repercussions resulting from the activities and movements of these fighters. Accordingly, this paper assesses the complex situation of these fighters, details their composition, explores the long-term challenges and risks arising from their presence, and addresses the issue of thousands of foreign fighters detained from ISIS, which continues to pose a significant threat to stability both within the region and beyond.

The Landscape of Foreign Fighters in Syria

Estimates of the number of foreign fighters who participated in the Syrian crisis (2011–2024) vary significantly, but generally range between 40,000 and more than 60,000 fighters from more than 100 countries during the peak years of the crisis, 2013–2017. The flow of foreign fighters into Syria fluctuated over time, with the period coinciding with the rise of the terrorist organization ISIS between 2014 and 2016 witnessing the highest numbers.

Between 2013 and 2015, the U.S. military reported an average arrival of 2,000 foreign fighters per month into Syria and Iraq. In December 2013, the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, a non-profit think tank in Kings College London, estimated that up to 11,000 individuals had joined the armed opposition in Syria. By January 2014, then U.S. National Intelligence Director James Clapper estimated that there were more than 7,000 foreign fighters in Syria on the rebel side alone.

Between 2016 and 2018, this rate slowed down significantly, dropping to fewer than 500 foreign fighters arriving per month in 2016. The number of foreign fighters in Syria continued to decline due to battlefield losses and international countermeasures. By 2018, Syrians constituted the majority of fighters within the armed opposition groups.

The motivations of foreign fighters involved in the crisis varied, but most were driven by extremist Salafi ideology. The largest groups of foreign fighters came from the Middle East and North Africa, especially Tunisia (approximately 6,000), Saudi Arabia (2,500), Turkey (2,100), and Jordan (more than 2,000). Western Europe contributed about 5,000 fighters, mostly from France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Sweden. Around 2,400 came from Russia, with other significant sources including the former Soviet republics (4,700), Southeast Asia (900), the Balkans (875), and North America (289). These fighters were distributed among multiple groups, foremost among them ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra (later Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham[HTS]), Al-Qaeda (later Hurras al-Din), and other Salafi armed extremist factions.

However, the presence of foreign fighters in Syria is not limited to opposition forces alone, especially after the national crisis took on a regional and international dimension. Iran was quick to supply the former regime with fighters from Iran and other countries, such as Iraqi armed factions and the Lebanese Hezbollah, as well as Pakistani and Afghan fighters, including the Liwa Fatemiyoun, which initially operated as a military unit before expanding into a full brigade in 2015. Overall, the number of Iran-aligned fighters in Syria increased significantly as Iran’s influence deepened there, rising from around 10,000 fighters in 2013 to between 15,000 and 25,000 by 2016, according to estimates by London’s Financial Times. However, these fighters left Syria with the change of regime, coinciding with the withdrawal of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard forces.

In contrast, while the number of foreign fighters within armed opposition groups has declined since 2018, those who remained, particularly within factions loyal to the HTS, played a significant role in the recent offensive that led to the collapse of the former regime’s forces. On the other hand, a large number of foreign individuals who joined the Islamic State (ISIS) remain in detention, primarily held by the SDF in northeastern Syria. Estimates suggest that around 8,200 foreign ISIS militants are currently in SDF custody, while their families are held in refugee camps such as al-Hol and Roj. This separate group of foreign fighters not aligned with the new government represents a significant and ongoing security challenge for the region. Moreover, the existence of these camps presents a complex humanitarian situation, with long-term concerns about the further radicalization of those detained within them.

Integration into the New Syrian Government

Some foreign fighting groups allied with the HTS remained active after the fall of the former regime in Syria. Although there is no precise estimate of the remaining number of foreign fighters, the most prominent groups include the Turkistan Islamic Party (2,500 fighters), Ansar al-Tawhid (200 fighters), Ajnad al-Kavkaz (250 fighters), and Ajnad al-Sham (300 fighters). With the formation of the new Syrian Army, these fighters were integrated into official military formations under a unified command structure. Independent foreign fighter groups were dissolved, and their members were formally incorporated into the Syrian Army. President Ahmad al-Sharaa emphasized the significant contributions of these foreign fighters in toppling the former regime, stating that those who helped bring down Assad deserve to be rewarded, and he hinted at the possibility of granting them Syrian citizenship in recognition of their efforts.

Theoretically, there are historical precedents for significant roles played by foreign fighters in various national armies. One of the most prominent examples is the French Foreign Legion, which has a long-standing history of integrating foreign nationals. Other examples include the incorporation of foreign-born soldiers during the American Civil War and the participation of international fighters in the Spanish Civil War during the 1930s who sided with the Republicans against the Nationalists led by General Franco.

In the modern context, Ukraine presents a similarly complex model. Since the outbreak of the war in the spring of 2022, foreign legions have been fighting alongside the Ukrainian army against Russian forces. Among them is the International Legion of Territorial Defense of Ukraine, which includes Polish, French, and Georgian fighters. Russia estimates that this legion comprises around 18,000 fighters from 85 countries worldwide.

The Syrian transitional government cites these historical and contemporary models to legitimize the presence of foreign fighters and to justify their integration into the Syrian army. However, the motivations, ideologies, and specific geopolitical consequences of these historical examples differ significantly from the current situation in Syria. As a result, public opinion among Syrians is deeply divided.

Some view this integration as a gesture of gratitude by the new leadership toward the foreign fighters who played a role in the regime’s downfall. Others see it as a pragmatic move, recognizing these fighters as a force that could be useful in the future if needed. Meanwhile, another view holds that the government had no real choice; failing to integrate them could risk them becoming a serious threat to the country’s emerging and fragile stability.

Nevertheless, this integration has not been accepted by another segment of Syrian society. Their rejection stems from various concerns, including doubts about the long-term loyalty of these fighters, fears that they may pursue agendas that clash with national interests, and concerns, particularly among minority communities, about the perceived extremism of some foreign fighters and the higher levels of violence often attributed to them.

In addition, the issue of foreign fighters is closely tied to the power dynamics within the opposition’s armed factions and their internal alliances. Many Syrian fighters who took part in the conflict feel marginalized due to the importance given to foreign fighters, particularly in light of the influence wielded by some of these foreign fighters, a number of whom have been appointed to key leadership positions. According to media reports, around 50 foreign fighters have been assigned to leadership roles, including six in senior positions within the intelligence services, the military, and the Republican Guard.

Among the most notable appointments is that of Abdul Rahman Hussein Al-Khatib, a Jordanian national holding the rank of brigadier general, who was appointed as commander of the Republican Guard. Additionally, about 50 other commanders have been appointed, including Abdel Bashari, the long-time leader of the Albanian contingent; Omar Muhammed Jaftshi; Egyptian national Alaa Mohammed Abdel-Baqi; and Abdulaziz Dawood Khodabardi, a member of the Turkic Muslim minority from China.

On the international stage, the integration of foreign fighters—especially those with known Salafi-jihadist affiliations—has sparked significant concern among Western governments. Washington, in particular, has called on the Syrian government to remove foreign fighters and to halt the appointment of such individuals to sensitive government positions.

Challenges and Concerns About Foreign Fighters

The primary challenge lies in the potential for foreign fighters to destabilize the region or pose a threat to international security, particularly given the ideological affiliations of many among them. There are growing concerns that individuals with a history of involvement in extremist groups might exploit their positions of authority within the new Syrian government to advance their ideological agendas. This raises fears that Syria could become a launching pad for attacks against neighboring countries or the West, especially at a time when the country continues to face various security threats. These include ongoing dangers from existing terrorist organizations such as ISIS, as well as from several rival armed groups that may not be fully integrated into the new military structure.

The presence of foreign fighters within the government risks further complicating these security threats, as the loyalties and priorities of such individuals may not always align with Syria’s broader national security interests. Moreover, some of them may oppose the transitional government’s foreign policy, particularly its openness to relations with the United States, and its willingness to consider normalization with Israel. Given that these fighters have limited options and few prospects outside Syria, especially as their home countries are generally unwilling to repatriate them, they face a stark choice: either rebel against the government or join extremist organizations such as Hurras al-Din or ISIS.

In fact, in May 2025, ISIS issued a call through its newspaper Al-Naba, urging foreign fighters within the Ministry of Defense to defect and join its cells, claiming that the new Syrian authorities were merely exploiting them to serve their agenda. This appeal also targeted dissatisfied fighters within the HTS, some of whom have already defected and joined factions outside the Defense Ministry’s structure, including Saraya Ansar al Sunnah, a group that follows an ideology closely aligned with ISIS.

However, there are growing concerns surrounding the potential involvement of these foreign fighters in acts of retaliatory violence, particularly those with a history of prior abuses or unlawful conduct. Multiple reports have documented the involvement of foreign fighters in violations committed during the coastal events of a government-led military operation in March 2025. This highlights the complexities introduced by the integration of such fighters and the impact it may have on reconciliation efforts—especially given Syria’s long history of social and sectarian tensions, the deep divisions exacerbated by years of conflict, and the prevailing perception of foreign fighters as being biased toward specific groups or complicit in sectarian violence.

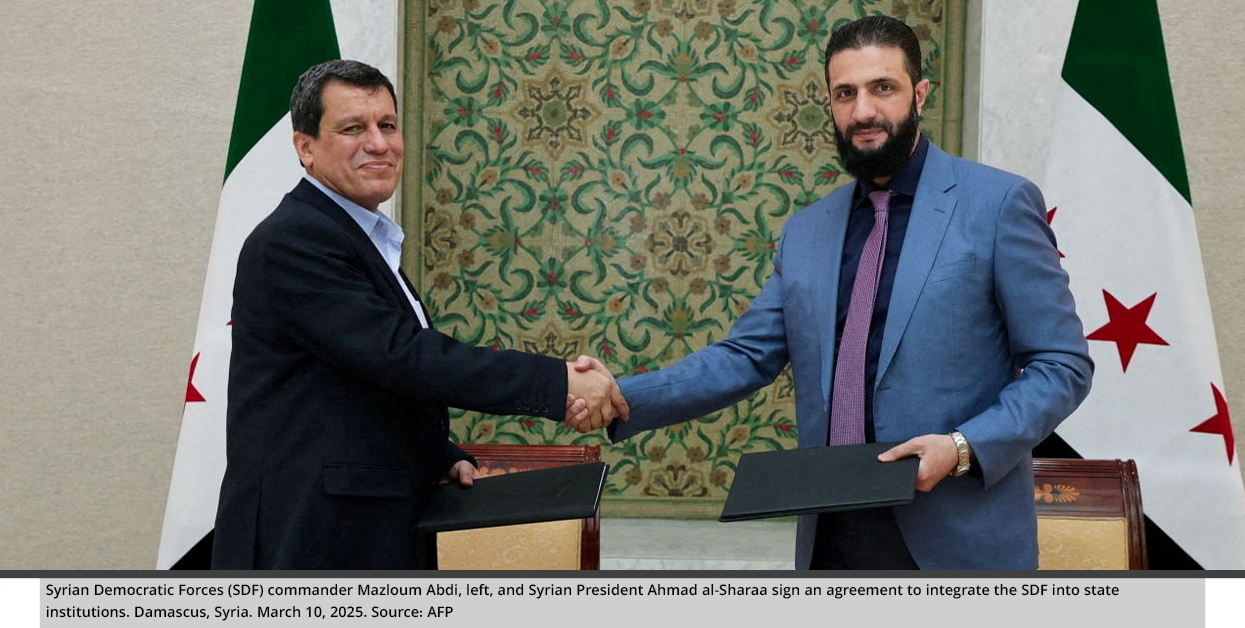

On a related front, the issue of detained foreign ISIS members and suspects, along with their families, currently held in northeastern Syria, presents a major and complex challenge for the international community. Nearly six years after the collapse of the so-called “caliphate” in 2018, the detention of approximately 26,000 foreign nationals continues. Recent leadership changes in both Washington and Damascus have created a potential—albeit narrow—opportunity to address this longstanding issue. Syrian President Ahmed Al-Sharaa could play a role in revitalizing efforts to resolve the matter, particularly in light of his political and military agreement with the Kurds in northeastern Syria, a region that still maintains a degree of de facto autonomy.

Despite America’s continued calls for all countries to repatriate their citizens from camps like al-Hol and Roj, emphasizing that these camps serve as incubators for terrorism and could lead to more extremism for another generation, many countries have shown great reluctance to bring back their nationals who joined ISIS. This hesitation stems from security concerns, legal complications related to prosecuting individuals for crimes committed abroad, and domestic political considerations.

Western security agencies have long expressed fears that returning foreign fighters could pose a significant terrorist threat, given their advanced combat training, connections to international terrorist networks, and the heightened radicalization many experienced during their time in Syria. The concern is that they may exploit these experiences to plan and carry out terrorist attacks in their home countries or elsewhere. This threat is further exacerbated by calls from some extremist Salafi groups encouraging their followers in the West to carry out such attacks.

As a result, countries have adopted various approaches to dealing with their foreign fighters. Some have opted to repatriate their nationals for prosecution under their domestic legal systems, while others have attempted to block their return by revoking their citizenship or challenging its validity. A third approach has involved deliberately avoiding any facilitation of their return, effectively leaving them in the custody of the Syrian Democratic Forces or other entities in Syria.

At the same time, the absence of a unified international strategy on this issue has contributed to the prolonged detention of these foreign fighters and their families, exacerbating the dangerous conditions they face. Moreover, the fate of intelligence databases and records related to these individuals presents an additional challenge. There is also the difficulty of distinguishing between those who pose a genuine security threat and those who were victims of ISIS or coerced into joining it, further complicating decision-making processes related to detainee transfers or intelligence sharing.

In general, the presence of a large number of foreign fighters in Syria, particularly those with extremist ideologies and combat experience, poses a significant risk with potential regional and international repercussions. Some Chechen fighters, who were previously active in northwestern Syria, have already participated in the conflict in Ukraine, highlighting the willingness of some of these individuals to deploy to various conflict zones whenever the opportunity arises. The combat experience gained during the Syrian crisis, combined with the extremist ideologies embraced by many of these fighters, renders them both willing and capable of engaging in other conflicts or carrying out terrorist acts in their home countries or elsewhere around the world.

Foreign Fighters Scenarios: HTS-Affiliated Faction Fighters and ISIS Detainees Held by the SDF

The issue of foreign fighters in Syria is divided into two main categories based on their current status: those who are integrated into the structures of the new state and the ISIS detainees held by the SDF. In reality, the scenarios for each category differ from one another.

Scenarios for Fighters in Factions Affiliated with the HTS

One: Full Settlement and Integration

This scenario represents a continuation of the current trajectory initiated by the new Syrian authority. It involves granting foreign fighters Syrian citizenship and allowing them to continue holding leadership positions in the military and security apparatus. This scenario is reinforced by several factors, including the transitional government's need for a loyal military force to support its authority, the desire to reward these fighters for their role during the crisis, and fears of a potential rebellion if they are excluded.

However, this scenario faces numerous challenges, foremost among them international pressure, particularly from Western countries, which have made the cessation of appointing foreign fighters to senior state positions a condition for engagement and the sustained lifting of sanctions on the country. Additionally, there are domestic concerns over the multiple loyalties of these fighters and their potential jihadist agendas, especially given the risk of escalating sectarian tensions, particularly as some of them have been involved in violations against minorities, especially along the Syrian coast.

Two: Gradual Demobilization

This scenario represents a middle-ground solution for the transitional government, aimed at responding to international pressure on one hand, and preventing a potential rebellion by foreign fighters on the other. It involves gradually demobilizing foreign fighters from sensitive governmental and military positions and replacing them with Syrian personnel, while also offering the possibility of integrating them into civilian sectors or providing incentives for their voluntary departure.

The likelihood of implementing this scenario increases as international pressure on the government intensifies, along with growing public discontent over the roles of these fighters, especially as their expanding influence within the state’s decision-making structures poses a potential negative impact on both domestic and foreign policy. A number of foreign fighters have already left military activity and started their businesses, with many such examples found in Idlib. This makes the expansion of this model a viable option, particularly if the government adopts well-structured implementation mechanisms. These could include, for example, rehabilitation and reintegration programs into civil society, financial compensation in exchange for voluntarily giving up military positions, and gradual retirement plans with certain guaranteed benefits.

Three: Repatriation to Countries of Origin

This scenario involves returning foreign fighters to their countries of origin, either voluntarily or forcibly, under international pressure or as part of bilateral agreements with the concerned states. In this context, reports have emerged about arrest campaigns carried out by Syrian security forces targeting foreign fighters, particularly Arabs. Deportation could be the next step, especially for Arab fighters, as their repatriation is easier compared to those whose home countries refuse to take them back due to security concerns, legal and political complications, or because they have been stripped of their citizenship altogether.

Four: Conflict and Elimination

This scenario points to the possibility of internal conflict erupting between different factions, or the targeted elimination of some foreign fighters by orders from the new leadership. The likelihood of this scenario increases if the current situation remains unchanged, as the continued integration of fighters with extremist ideologies into state structures may lead to growing radicalization and deepen divisions between various groups. This scenario could also occur if the authorities take measures to address the issue of foreign fighters in ways that displease them or sharply exclude them from positions of influence.

Scenarios for ISIS Detainees Held by the SDF

1- Repatriation Scenario: This involves returning the detainees to their countries of origin for trial, a course of action consistently advocated by the United States. However, it faces resistance from several countries, particularly in Europe.

2- Local Trial Scenario: This involves trying the ISIS detainees within the new Syrian judicial system, or through the establishment of a special international court that oversees their trials in Syria.

3- Rehabilitation and Reintegration Programs Scenario: This involves implementing comprehensive programs to deradicalize and rehabilitate low-risk detainees, paving the way for their reintegration into society or their return to their countries of origin.

4- Escape and Resurgence of ISIS Scenario: This is the most dangerous scenario and could occur alongside any new security deterioration in Syria or a sudden withdrawal of international forces from detention areas, potentially leading to a mass escape of ISIS members and the group's reformation.

Finally, the coming period is likely to witness a gradual approach involving the reduction of foreign fighters’ influence within state structures under international pressure, alongside the implementation of rehabilitation and reintegration programs for lower-risk individuals, and the adoption of strict security measures to deal with more extremist individuals. As for ISIS detainees, international negotiations over their fate are expected to continue, with the possible return of some to their countries through limited bilateral agreements.

Overall, Syria remains in a complex and unstable phase, and foreign fighters continue to pose a threat, one that risks ideological clashes and serves as a constant warning of the potential return of extremism and terrorism, whether through ISIS or other groups that may emerge in the future.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية