India and the Dilemma of Balancing Its International Relations: The Ukrainian Crisis as a Model

Policy Analysis | This paper is seeking to analyse Indian foreign policy through the model of the Ukrainian crisis. It is also seeking to foresee the outcome of the Indian position on that crisis by addressing the historical, economic, military, and geopolitical determinants of the Indian foreign policy. It presents the Indian position chronology of the development on the Ukrainian crisis, as well as the opportunities that such crisis may offer to India despite the caveats that may be imposed on it.

by Sahar Muhammad

- Release Date – Sep 7, 2022

The general feature of India’s foreign policy on global crises is based on the principle of neutrality. The Ukrainian crisis is the most recent example of this policy. It is also a real test of the principle of neutrality to preserve India’s interests and the independence of its political decision.

This policy comes in the context of a geographic location full of political and economic challenges. India is surrounded by two nuclear powers, Pakistan and China, which have globally contradictory positions from India, which is more closely aligned with the United States.

However, New Delhi’s position towards the Ukrainian crisis was established according to historical foundations that had a role in setting India’s strategies, policies, and alliances. Such foundations are important to be understand and review, along with current economic and geopolitical determinants, for the purpose of understanding the dimensions and levels of the Indian policy’s neutrality, which may lead us, by its virtue, to foresee the outcome of the Indian position on the Ukrainian crisis.

First: The Historical Determinants

From the moment the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act in 1947 that ended Britain’s colonial era, New Delhi adopted a foreign policy based on the principle of autonomy and rejected alliances that could influence its independent decisions.

This policy gained more importance in 1955 after India co-founded the Non-Aligned Movement, a forum that now includes 120 countries that oppose colonialism and the acquisition of states’ sovereignty and independence.

With the end of World War II and as the competition between the former Soviet Union and the United States became intense, India tried to build balanced relations. However, apart from theoretical aspects of its foreign policy rules, then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, preferring socialist ideas, wanted to strengthen his country’s relations with the Soviet Union. Pakistan, on the other hand, sought to strengthen its partnership with the United States.

In view of the border dispute between India and Pakistan over the Kashmir region and amidst Britain’s efforts to include Pakistan in the Baghdad Pact in 1954, New Delhi sensed the dangers of the relationship between Islamabad and the West. India’s relations with the Soviet Union was largely based on a strategic partnership in the military fields. For instance, the Soviet Union was the first supplier of Indian weapons, especially after the U.S. embargo on its arms exports to the Indian subcontinent during the 1965 Kashmir War.

The Indian experience of neutrality came to an end after its move to annex Goa and the small coastal enclaves of Daman and Diu overlooking the Arabian Sea ended Portuguese sovereignty over those islands. The United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Turkey applied to the United Nations to demand the withdrawal of Indian troops, which was opposed by the Soviet Union.

Against the backdrop of India’s defeat by the Chinese Army in 1962 and China’s dispute with the Soviet Union over ideological implications regarding communist concepts and implementations, the India and Russia’s relationship solidified in 1971 with the signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation

Following all of the above, India shifted from a strategy of neutrality towards a strategy of axes that was based on Moscow’s support for New Delhi regarding India’s supremacy in the Kashmir issue and establishing India’s position in South Asia. Also important was the advanced role of the Soviet Union at that time in international forums. It used the right of criticism against the UN Security Council resolutions on Kashmir in 1957, 1962 and 1971 to end attempts at international intervention in the region. In return, India was silent on the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979.

However, there is a decisive moment to Indo-Soviet relations after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, a point with which India reshaped its foreign policy and responded to the unipolar international order by establishing closer ties with the United States.

India’s relations with the United States achieved remarkable developments after the escalation of terrorism, which was one of the reasons that America changed its position on the Kashmir issue. Having first supported the Pakistani position on holding a popular referendum to determine territory’s situation, America later supported bilateral negotiations between the two neighbours regarding Kashmir. In 2008, New Delhi signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with Washington that allowed India to join the global nuclear club.

Meanwhile, India maintained its relations with the Russian Federation. In 2000 Russian President Vladimir Putin visited India to sign 17 joint agreements to develop cooperation between the two countries. Then, the year 2001 witnessed a major deal between the two countries that guaranteed India would be allowed to produce 140 Sukhoi fighter jets, a qualitative shift in the Indian Air Force.

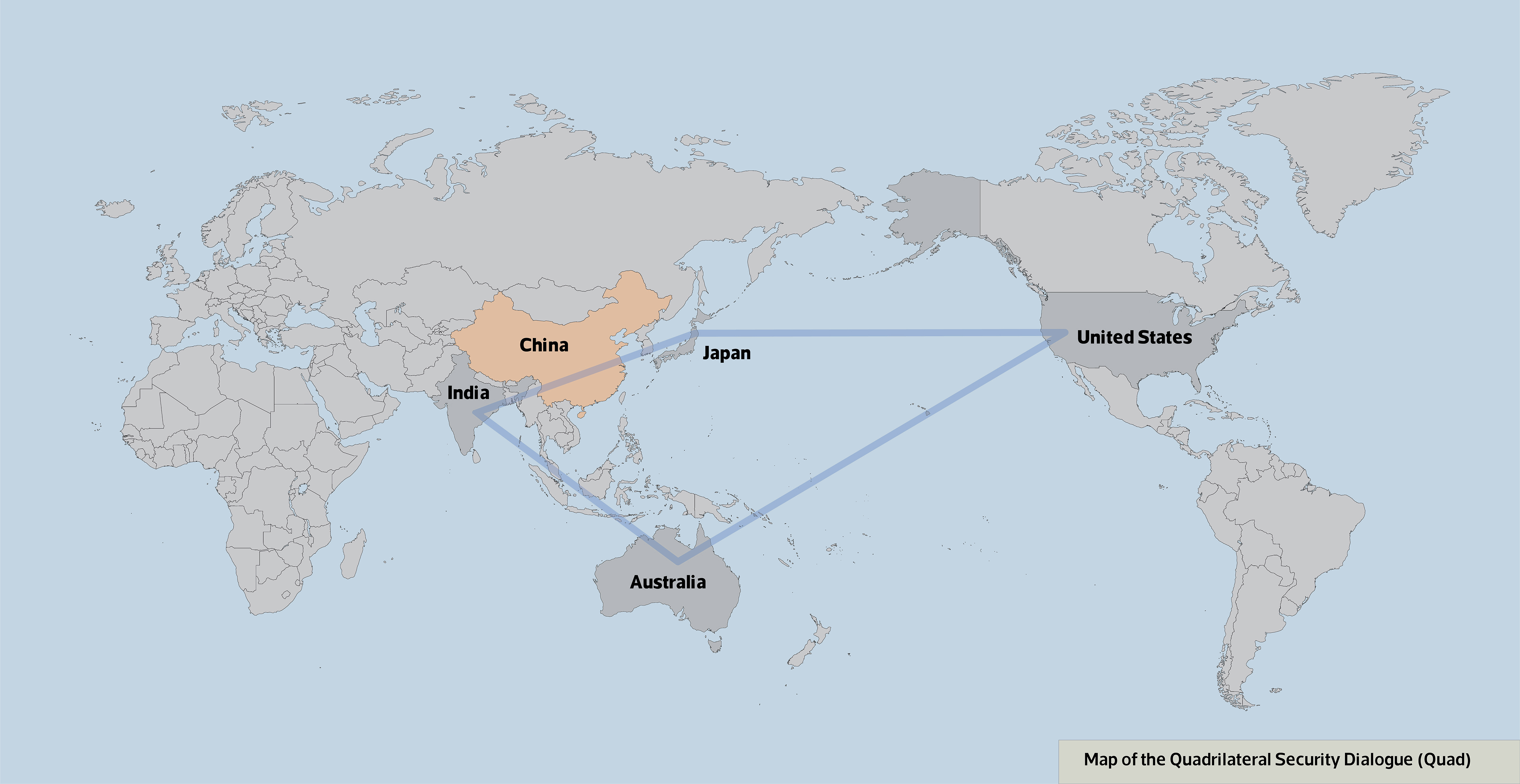

Nevertheless, all these attempts to adopt a balanced Indian foreign policy were not enough to keep pace with the changes in its surroundings, especially the rapid rise of China. This prompted New Delhi to revive the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), a forum between India, Japan, Australia, and the United States to strategically counter China’s economic and military rise. In 2016, the bilateral logistics exchange agreement with the United States allowed the latter’s use of Indian air and sea spaces. In 2018, the two countries signed prominent security agreements.

Second: Economic and Military Determinants

Since the beginning of this century, India has emerged as a global economic power with a $2.94 trillion economy. India adopted economic tracks relatively independent of its political tracks. Its trade exchange with Russia reached about $10 billion during 2019–2020; U.S. investments in India reached about $46 billion during the same period.

Reflecting its need for crude petroleum as the third largest global consumer, India’s petroleum imports from Russia in May 2022 rose by about 13.4 percent compared to the same period in 2021. The rise was due to preferential prices Russia offered India as a means of avoiding the impact of Western sanctions. India also increased its U.S. petroleum imports by 11 percent, bringing the U.S. share in the Indian market to 8 percent during the same period.

By contrast, Russian arms sales to India are exceptional. About 60 percent of India’s defense forces are equipped with Russian weapons. The two countries cooperate in the production of BrahMos cruise missiles, Su-30 aircraft and T-90 tanks, as well as plans for India to manufacture AK-203 rifles.

The United States continues to militarily support India to compensate for its need for Russian weapons and to bring it into the Western side against China. Washington sees New Delhi as a strategic partner to the West against China. Though the

United States continues to exert pressure to cancel India’s arms deals with Moscow, though but such efforts are not always successful due to India’s preference of Russian military relations, especially in joint weapons manufacturing programs; the privileges granted by Moscow in defensive weapons; and India’s ability to integrate its domestic weapons with Russian fighter jets and warships, which are affected by Western sanctions against Russia. Moreover, Russian defense exports are conducted without political oversight, unlike the U.S. weapons, which are generally subject to congressional approval.

Third: Geopolitical Determinants

The desire to undermine China’s rapid rise remains a shared point of commonality in India-U.S. relations, as the strategies of the U.S. blockade against China depend on placing India alongside Australia and Japan in the Quad as part of the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region.

In October 2021 India, the United States, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates formed a quadrilateral group, I2U2 (taken from the first letters of each country), to restructure the routes of global supply chains and international trade lines away from China and its “Belt and Road” project. In addition, India moved to another trade belt, linking it to European markets through Middle Eastern and Greek ports. India’s latest step in this regard is its rapprochement with the Taliban after several meetings between Indian officials and Taliban leaders.

Will India be able to deal with the Ukrainian crisis within the previous determinants?

The answer to this question leads us to highlight the Indian position on the Ukrainian crisis. India did not take any hostile position or absolute alignment with the West towards Russia. Instead, it abstained from voting on January 31, 2022, as to whether the UN Security Council should consider the Ukrainian issue (before the start of Russian military operations) a threat to international peace and security. As one of the non-permanent members of the Security Council, India also refrained from condemning Russia’s recognition of the independence of the Donetsk-Lugansk region in eastern Ukraine.

With the start of the Russian military operation in Ukraine in late February 2022, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered a speech calling on both parties to follow a negotiating path through diplomacy, declaring that “India is neutral in the conflict” and confirming that India will abstain from voting on the UN General Assembly resolution condemning “aggression against Ukraine” on March 2. India also abstained from voting on the suspension of Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council on April 7.

The determinants of the Indian position on the Ukrainian crisis remain dominated by India’s ability to balance its relations with major countries. India became part of the “Quad” that confronts China as well as a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the BRICS group led by China and Russia. Clearly, India’s economic relations with Japan and the United States is just as important to its relations with Russia and China.

In its position on the Ukrainian crisis, India senses opportunities and caveats.

Among the many favorable opportunities for India, Russian petroleum is at the forefront with its unlimited quantities and prices 20 percent lower than international record prices. New Delhi benefited from the mechanism of dealing in rupees and rubles, which spared India the burden of pressure on the value of its currency to provide the dollar needed to buy oil, as was the case in the past. In addition, opportunities for Indian companies in the Russian market, especially in the pharmaceutical sector, expanded after many Western companies left Russia due to sanctions.

The rivalry between Russia and the West provides a margin for India to maximize its position as the two major powers seek to win India over to their side. On the other hand, the rivalryalso accelerates the transition to a multipolar international order in which India is an active presence. No matter how long the Ukrainian crisis lasts, it is steering the existing world order towards a new era in which New Delhi seeks to reserve an advanced position.

In addition, the Ukrainian crisis prompted Western countries and the “Quad” alliance to tighten their positions on China, which pushed forward the pace of Indian, American, and South Korean relations. The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden is considering providing military funding to India worth $500 million.

The repercussions of the Ukrainian crisis are multiple for both India and Russia. New Delhi relies on Russia for armaments and military equipment. Western sanctions affect Russian defense capabilities, their exports, and supply routes, which, in turn, affect their recipients, including India. In addition, the emergence of a “no limits” Sino-Russian strategic partnership ahead of the Ukrainian crisis raised New Delhi’s doubts about trusting its security partnership with Russia in the event a conflict may arise between New Delhi and Beijing. Not isolating Russia and China is in India’s best interest so as not to depend entirely on the United States, which has recently been critical of India’s Hindu nationalist policies.

Moreover, India’s failure to condemn Russia’s military operation in Ukraine may be understood by Beijing as support for its military adventures in India’s vital ocean, justification for annexing Taiwan, or even seizing resource-rich Siberia.

On the other hand, if the security situation in Europe worsens, it could divert America’s focus away from its primary areas of interest in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, potentially providing China with more leeway along its borders with India and in the South China Sea. Additionally, the protracted Ukrainian crisis could impact the trajectory of Indo-European relations, possibly leading European nations to turn towards China in an effort to detach it from Russia. This shift would have negative consequences for India’s political and economic standing, as it has positioned itself as a valuable mediator between the West and Moscow.

The repercussions of the Ukrainian crisis may also affect the status quo in the Kashmir region since Moscow’s justifications for its behavior against Ukraine are similar to those offered by Pakistan and China against India regarding the region in terms of historical claims and ethnic and religious ties. Given Russia’s tendency to side with Pakistan, this is especially troubling to India.

Finally, the Ukrainian crisis is a moment of truth for Indian foreign policy, especially its strategy of multi-directional alliance. The Indian position remains dependent on the ultimate results of Russia-Ukraine crisis, its development, and the extent of the intensification of the confrontation between Russia and the West.

* The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author. Strategiecs shall bear no responsibility for the views and/or opinion of its author on security, economic, social, and other issues, as they do not necessarily represent the views of the Think Tank.

Sahar Muhammad

Researcher in international relations

العربية

العربية