The 20th Parliamentary Landscape and Prospects of Political Modernization

This paper presents an analysis of how results of the recent Jordanian parliamentary election will affect the kingdom’s political parties. It proposes a number of scenarios regarding the parliamentary landscape of the 20th council, as well as the trajectory of political modernization.

by STRATEGIECS Team

- Release Date – Sep 19, 2024

This paper analyzes the results of the parliamentary elections in Jordan, discussing the anticipated trends for the 20th parliamentary scene. It examines the potential scenarios for the upcoming council in light of the new electoral law and the political modernization process. The paper highlights the significant differences in the current council’s composition compared to previous councils, as well as the considerations linking Jordan’s reform trajectory to external conditions and factors. This includes historical contexts from 2005 and 2012, and what may unfold due to the war in Gaza and its repercussions on the kingdom and the region.

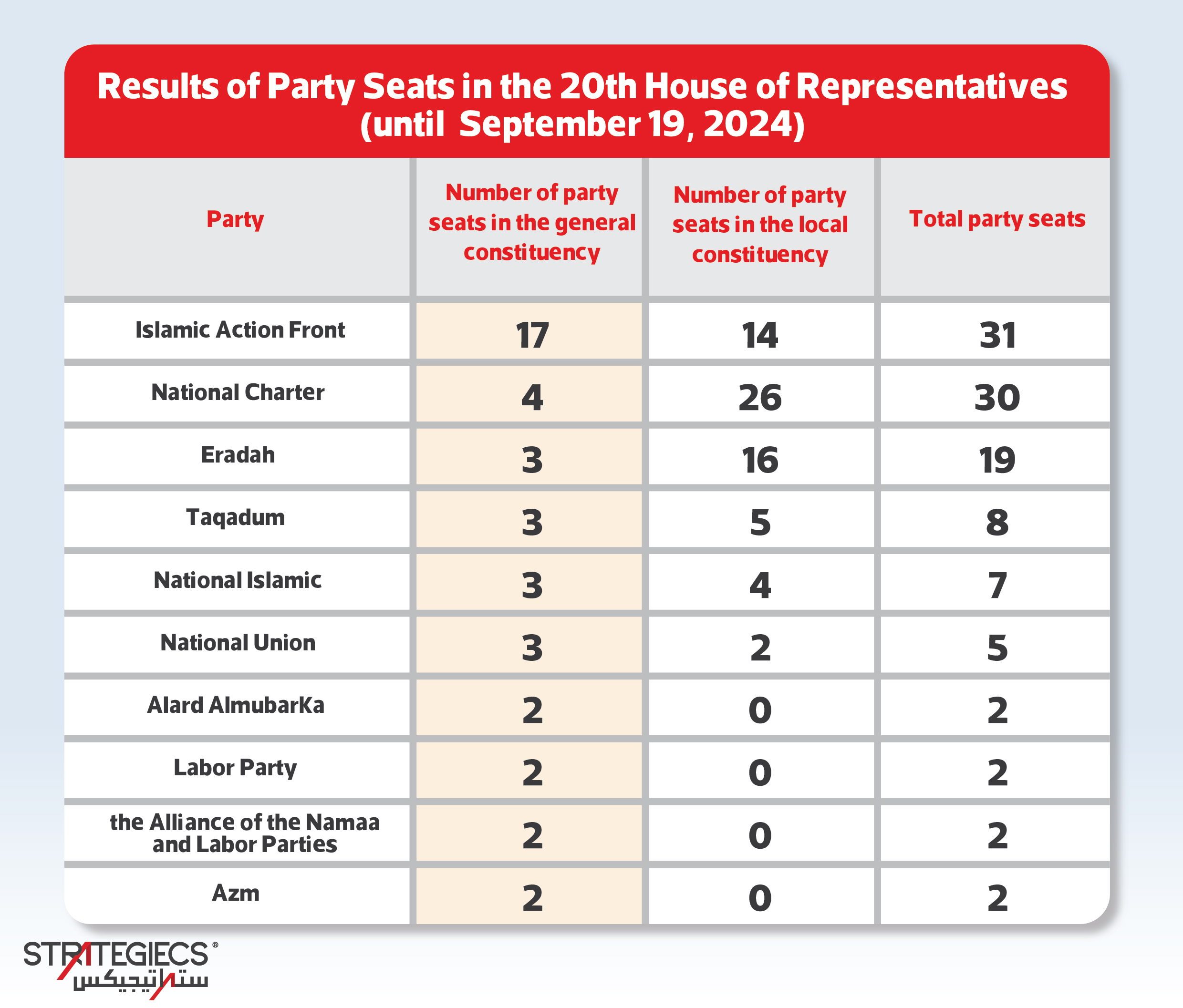

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan recently held its Parliamentary election for the 20th council with wide participation of the parties according to a new electoral law. The Islamic Action Front (IAF) won the largest number of seats, followed by the National Charter Party and then Eradah Party. In terms of local lists seats, the National Charter Party led among the parties, followed by the Eradah Party and then the IAF.

The anticipated trends for the new council can be summarized in three points. First, the composition of the parliament is expected to remain stable, based on three determinants: the party bloc that exceeded the threshold of 10%, parties that didn’t exceed the threshold of 10%, and the individual deputies. It is likely that the parliament will feature two types of parliamentary blocs: party bloc and parliamentary groups in this scenario. Second, there is a trend toward forming alliances and coalitions, in light of two key factors: the formation of a parliamentary majority or the establishment of an opposition minority. Third, the parliamentary composition is likely to maintain the Islamic Action Front as the most effective bloc.

The potential scenarios for the upcoming council can also be categorized into three outcomes. The first scenario is the successful implementation of the electoral process, leading to a transition to the next phase of political modernization. The second scenario involves a limited success of the experiment, prompting amendments to the electoral law. The third scenario is one of failure, resulting in a complete overhaul of the electoral law. Each of these scenarios is linked to a range of internal and external determinants, which the paper analyzes in detail.

The paper also highlights the significance of the path emerging from the Royal Committee for Political Modernization for the state, while acknowledging the surrounding risks. These risks include the behavior of political parties and the intertwining of Jordan’s reform trajectory with external conditions, such as the implications of the war in Gaza and the West Bank and the accompanying regional escalation.

Additionally, it addresses Iran’s efforts and its proxies to sway public sentiment in favor of Gaza against official stances regarding the conflict. The position of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan is also discussed, particularly as they claim to have achieved their best electoral results in the kingdom’s history. Given the weakened state of the Brotherhood’s branches in various regional countries and the divisions between the center and its branches, they may attempt to position themselves as a regional and international center, potentially making the country a battleground for political Islamic activities or a launching point for intervention in other nations' affairs.

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan held its parliamentary election for the 20th council on the morning of September 10, 2024, and announced the results on the next evening. The election was held with a wide participation of parties according to a new electoral law for the parliament, enacted in April 2022, which included updates in the electoral system. Notably, the voters were given two votes: one for a closed party list and the other for an open list at the local level across 18 electoral constituencies.

This paper presents an analysis of the results of the recent Jordanian parliamentary elections, particularly focusing on the party aspect. It proposes a series of scenarios related to the parliamentary landscape of the 20th council and the trajectory of political modernization.

The Party Landscape in the 20th Council Elections

The 2024 Jordanian parliamentary elections featured a wide party participation for forming the 20th House of Representatives under the new electoral law, which allowed voting at two levels: a general vote for a closed party list and a local vote for open lists. According to data from the Independent Election Commission in Jordan, the voter turnout in the kingdom reached 32.25%, with 1,638,351 voters out of 5,115,219 eligible voters. This marks an increase of over a quarter of a million voters compared to the previous election cycle, which had a turnout rate of 29.9%.

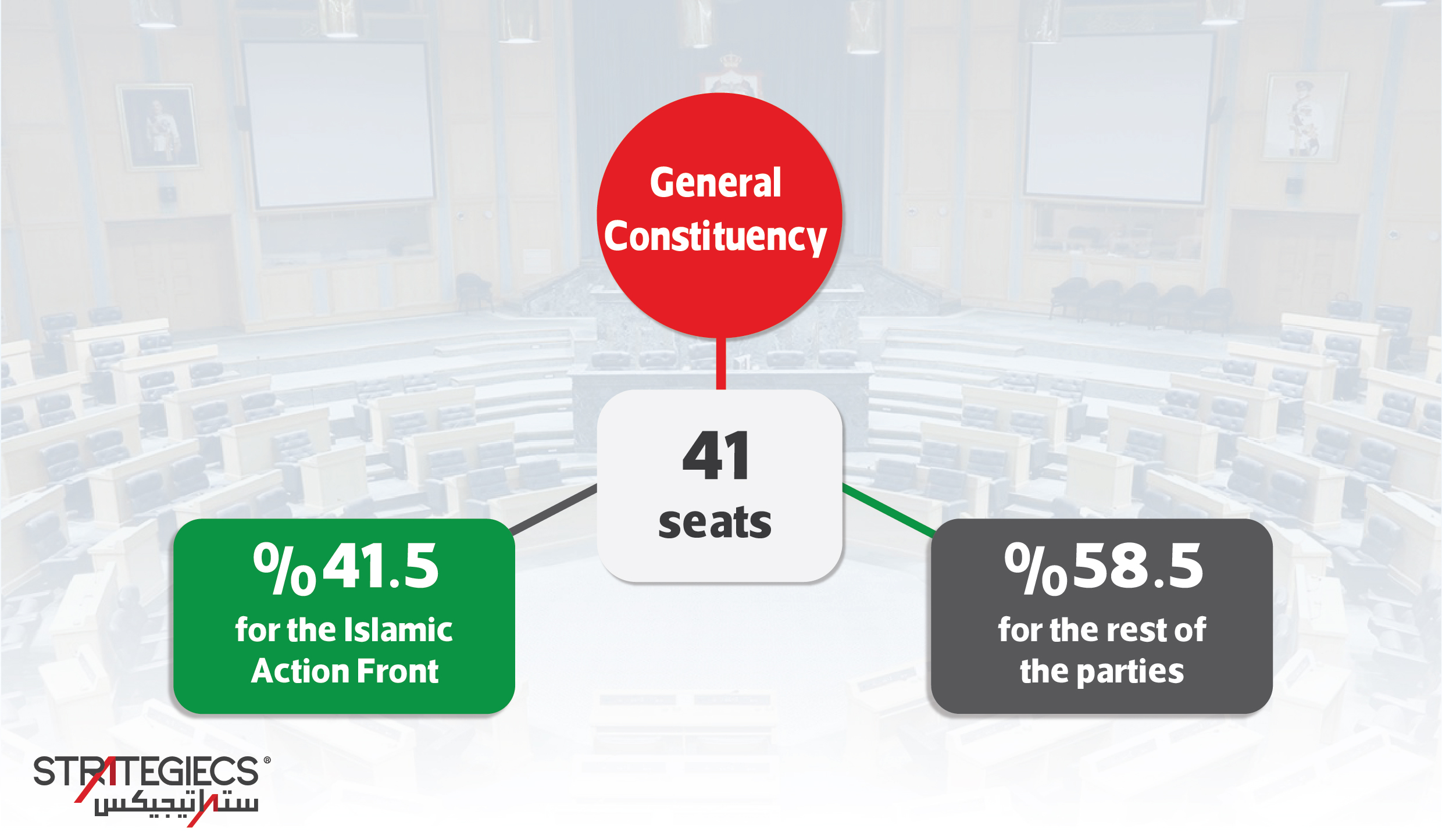

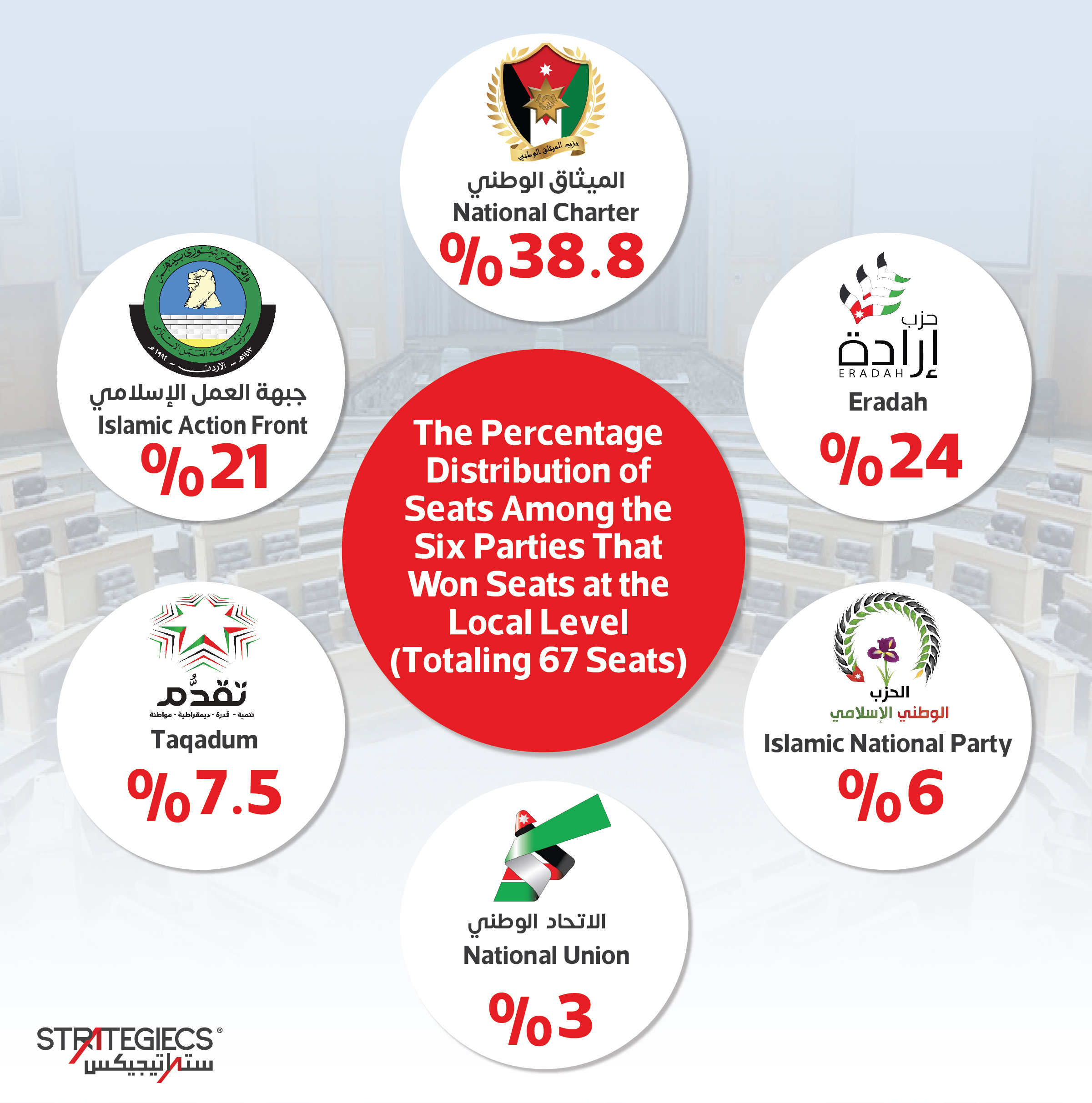

The election law specified that the number of seats in the 20th House of Representatives is (138), an increase of (8) seats compared to the 2020 elections. Of these, (41) seats are allocated for the general constituency and (97) for local constituencies. The winning parties secured a total of (108) seats from both the general and local constituencies, making the proportion of party members (78.3%) of the composition of the 20th House of Representatives. This proportion breaks down to (29.7%) for the general constituency based on the (41) seats and (48.5%) for party members in the local constituencies, which total (67) seats.

The IAF Party secured the largest number of seats among all parties in both the general and local lists, with a total of (31) seats. It was followed by the National Charter Party with (21) seats, according to the announcement from the Independent Election Commission. However, it was later reported that the total had increased to (30) seats after announcing nine new names of winning candidates in the local constituencies affiliated with the party. Following these, Eradah received 19 seats, Taqadum (Progress) Party received eight, the Islamic National Party received seven, and the National Union Party received five. Additionally, the Alard Almbarka Party, Jordan Labor Party, Azm Party, and the alliance of the Namaa and Labor parties each received two seats.

The results of the elections reflected several new indicators in the history of the electoral process, in accordance with its wide party participation imposed by the path of political modernization. This calls for analysis and discussion on this axis according to the following headlines:

The General Party Constituency Result

36 out 38 registered parties in Jordan participated in the parliamentary elections, 10 of which won seats in the general constituency that the new law has allocated 41 seats for parties. The following numerical arrangement represent the distribution of the 41 seats in the party general constituency, including the quotas (Circassians/Chechens, and Christians) on the ten winning parties.

The IAF secured the highest number of seats in the general constituency compared to the other nine parties, obtaining 17 seats out of the 41 allocated for parties, while all other parties combined received 24 seats.

The total number of votes cast in all lists of the general constituency was approximately 1,378,000, of which the IAF Party received 464,350 votes, accounting for about 45%. The party ranked first in 17 out of 18 electoral constituency, coming in second to the Alard Almbarka Party in the Badia Central constituency. IAF’s highest number of votes in the general list was in the Irbid First constituency, with approximately 50,000 votes, followed by the Amman First constituency with about 45,000 votes. In terms of the percentage of total votes in the local electoral district, the highest was in the Tafila Governorate at 55.3%, followed by the Aqaba Governorate at 46.3%, then the second constituency of Amman and Ma’an at 45.8% and 44.3%, respectively.

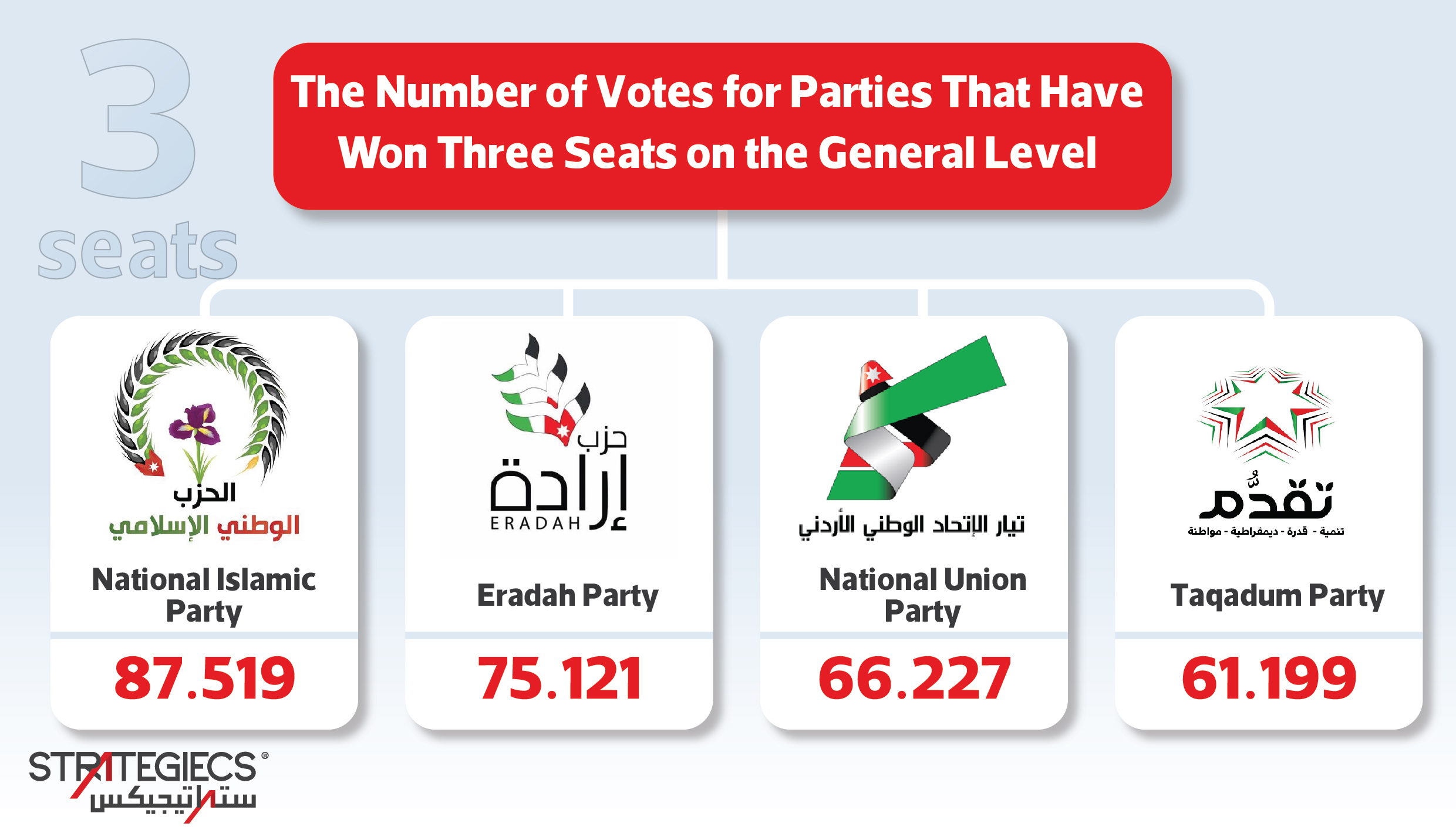

Following the IAF in the number of votes in the general constituency is the National Charter Party, which received 93,650 votes, representing all the votes for the four seats it won. The parties that won three seats varied in the number of votes they received are listed below in descending order:

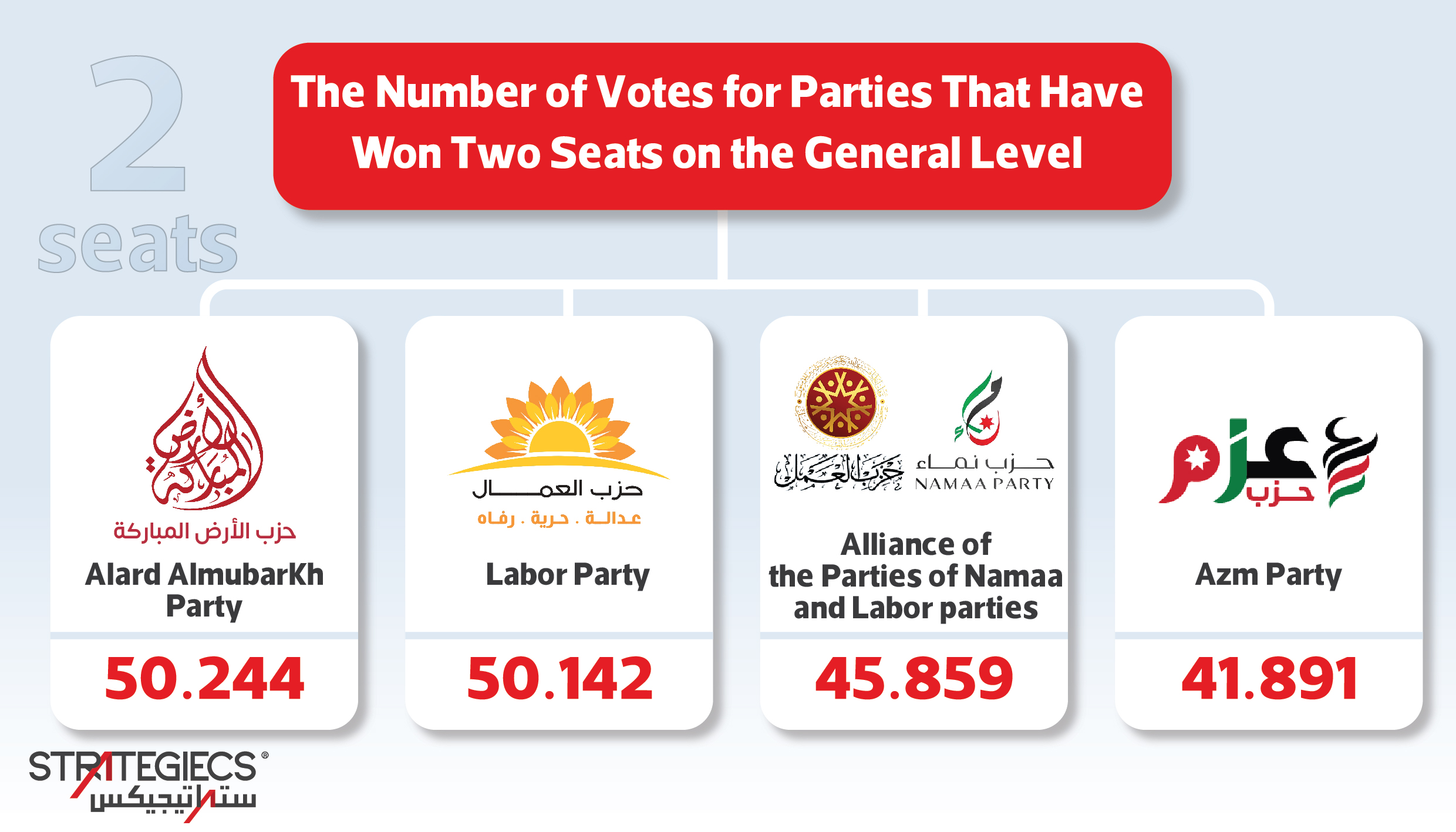

The number of votes for the remaining four parties out of the ten, each of which won two seats in the general constituency, is as follows in descending order.

According to the results from the Independent Election Commission, the National Charter Party leads in the number of seats among the parties in the local constituency, with 17 representatives. This is followed by the Eradah Party with 16 representatives, the Islamic Action Front with 14, and finally Taqadum Party with five.

Although the difference in votes among the three parties with the highest total number of seats in the 20th Parliament— the Islamic Action Front, National Charter Party, and Eradah—is minimal in the local district, the number of party representatives is expected to increase. On September 12 the National Charter Party announced its victory in securing the highest number of seats in the local constituency, having won 26 parliamentary seats from the local lists, which means there is an increase of nine representatives added to the 17 previously announced by the commission. This increase is in the context of these nine winners who competed in the free competition process and were announced as members of the National Charter Party after the results were released. This situation may also apply to other parties, such as Eradah and Taqadum, in the upcoming phase until the opening of the 20th parliament.

The other difference between the Islamic Action Front and other parties regarding the local list is that, unlike other parties, the IAF is the only party that disclosed the names of its candidates in the local electoral constituency. Consequently, the local votes cast for IAF candidates were largely given based on political representation, regardless of the individual candidate. In contrast, votes for other parties were typically cast according to the individual candidates on the list.

Additionally, the IAF secured four seats for women in the local constituencies out of the 18 allocated for women’s representation, as well as one Christian quota seat out of the seven designated for local seats. The party also won two seats in the Circassian/Chechen quota allocated for local constituencies.

The total number of votes in the local constituencies was 1,101,967. The National Charter Party received approximately 219,000 votes, which corresponds to the total number of votes for the 26 seats it won; the IAF secured 14 seats with around 159,000 votes; the Eradah Party won 16 seats with a total of more than 119,000 votes; and the Taqadum Party received about 54,000 votes in the local lists.

Scenarios for the Upcoming Parliamentary Scene in Light of Party Pluralism

The election results have brought about a new composition for the House of Representatives, differing from the usual structure of previous councils. The current council comprises 108 party representatives, with four main parties dominating: the Islamic Action Front, the National Charter Party, Eradah Party, and Taqadum Party, in addition to members from other parties such as the Islamic National Party. The number of seats held by these parties ranges from two to 31.

This composition is expected to impact the nature of the council, characterized by party pluralism, in terms of majority and minority dynamics, potential alliances and their party-related and non-party justifications, as well as the determinants of the relationship with the future government and its regulations, especially in light of a set of active and interactive factors. In this context, the following scenarios for the upcoming parliamentary scene can be outlined.

Scenario 1: Stability of the House of Representatives Composition

The formation of the House of Representatives based on the composition resulting from the electoral process means that the council will be quite similar to previous councils, particularly in terms of the centrality of the parliamentary blocs compared to the limited number of independents. However, the 20th parliamentary council has seen the establishment of three party blocs emerging from the election results prior to its convening, along with the possibility of new parliamentary blocs forming after it convenes. In light of this, the shape of the upcoming council will be as follows.

- Party Blocs Exceeding the 10% Threshold

The council will open with the presence of three parliamentary blocs produced by the elections, comprising representatives from the Islamic Action Front, the National Charter Party, and Eradah Party. These parties meet the requirements for forming blocs according to the internal regulations, which stipulate a minimum number of members equal to at least 10% of the council. The representatives of these blocs will total 80 members, accounting for approximately 58% of the council’s members.

In reality, the three party blocs possess the same influential capacity and relative weight in utilizing various legislative and constitutional oversight tools. They can all question ministers or propose laws; however, none of them has the sufficient number of members needed to propose a vote of no confidence against the government, which requires 33 representatives. These blocs are often seen as a pressure tool against the government in the House of Representatives.

Therefore, it is likely that the party blocs, particularly the Islamic Action Front, will seek to increase the size of their parliamentary bloc by forming alliances with smaller parties or independents. Conversely, the other two blocs aim to balance the weight of the Islamic Action Front. For instance, the National Charter Party quickly announced that its members in the council number 30 representatives, despite the registered number with the commission being 21. This suggests that the party is preemptively seeking to include several winning independent representatives before the council convenes.

- Parties Below the 10% Threshold

There are seven parties with a total of 28 members in the House of Representatives, but none of them has the required percentage to form a parliamentary bloc. Consequently, it is expected that:

1- The three previous parties will offer invitations to these seven parties to join their parliamentary blocs.

2- The next three parties in terms of the number of seats (Taqadum, the Islamic National Party, and the National Union Party) may prefer to negotiate to form a parliamentary bloc. A coalition between the Taqadum Party and the Islamic National Party could form a parliamentary bloc with 15 representatives, and similarly, the National Union Party could join forces with Taqadum.

3- The remaining four parties, each holding two seats, need to either join the parliamentary blocs of the Islamic Action Front or the National Charter and Eradah parties. This is a potential goal for the three party blocs, each seeking alliances to achieve a parliamentary majority.

4- There is a possibility of an agreement between the parties with two seats and the three parties (Taqadum, the Islamic National Party, and the National Union Party) to form one or more parliamentary blocs, allowing the smaller parties to gain a better voting weight compared to joining the three larger blocs of the Islamic Action Front, the National Charter, and Eradah.

- Independents

There are 30 independent representatives in the House of Representatives, a number that theoretically allows for the formation of a large bloc to compete with either the party blocs or two smaller blocs. However, this remains unlikely due to the inability of independents to organize their work collectively, especially with the presence of more experienced representatives from previous parliamentary sessions within the party blocs, particularly given the high number of first-time representatives. This suggests that independents face two possibilities: 1) remaining as independent representatives or 2) joining existing or forming blocs.

On the other hand, the number of independents may increase if representatives from parties with limited seats do not form a bloc or join existing blocs and instead choose to represent their parties in the council as independents. This is highly probable and is supported by the calculations of party representatives more than by the considerations of independent representatives, especially since the joining of party representatives to the three main blocs could enhance the strength of those blocs at the expense of smaller parties in the council. This would limit the ability of the parties with limited seats to implement their own policies, whether popular or aligned with their ideology, thought, and electoral programs.

Conversely, there are advantages to joining a larger party or parliamentary bloc. In light of the party blocs’ need for a majority, the negotiating weight of parties with limited seats increases, allowing them to secure positions in committees or bodies of the council that they would not have obtained if their representatives preferred to remain independent. Therefore, this group gains significance as a target for recruitment, particularly by the National Charter and Eradah parties, to compensate for the seat gap with the Islamic Action Front and the National Charter regarding Irada, or to achieve a majority for the National Charter.

In light of this trend, it is likely that the House of Representatives will witness two types of parliamentary blocs:

1- Party Blocs: This includes the blocs of the three parties that exceeded the 10% threshold.

2- Parliamentary Blocs: These may be formed by parties with fewer representatives, independents, or a combination of both.

This situation represents a real test for the concept of parliamentary blocs, which was applied for the first time in the 17th House of Representatives. Party blocs are considered the global standard for parliamentary groups, implemented as an alternative solution to the absence of parties in the council. Historically, such groups have often suffered from fragility and control by influential representatives, alongside a lack of political and ideological foundations among their members.

However, the upcoming experience—in light of the internal regulations of the House of Representatives, which may see amendments to the 2022 election and party laws—assumes significant changes between the parliamentary and party blocs. This is particularly relevant concerning membership rules and the ability of members to withdraw, which will not be available to party members. Additionally, the durability and continuity of these blocs will differ; the party blocs of the parties that exceeded the 10% requirement will remain stable throughout the council’s term, while parliamentary blocs may experience changes in membership at the start of each permanent session, or even dissolve altogether.

Scenario 2: Formation of Parliamentary Alliances and Coalitions

The changing composition of the House of Representatives, with an emphasis on party members at the expense of independent representatives, may lead to more advanced and developed parliamentary practices. This evolution could move beyond the traditional experience or form of parliamentary blocs to the formation of alliances and party coalitions within the parliament. This has implications in global experiences regarding majority and minority dynamics, particularly concerning their relationship with the government and their degree of control over the parliamentary agenda. This indicates that the parliamentary scene is heading in multiple directions.

First: Formation of a Parliamentary Majority

The formation of a parliamentary majority through a bloc comprising half or more of the House of Representatives is possible, given the similarities among several parties that successfully elected their candidates. Parties such as the National Charter, Eradah, Taqadum, the National Islamic, the National Union, Azm, and Al-Arad Al-Mubarak are relatively new, and their political discourse aligns with official rhetoric. Together, these parties hold a total of 73 seats in the council, theoretically enabling them to form alliances that could achieve an absolute majority.

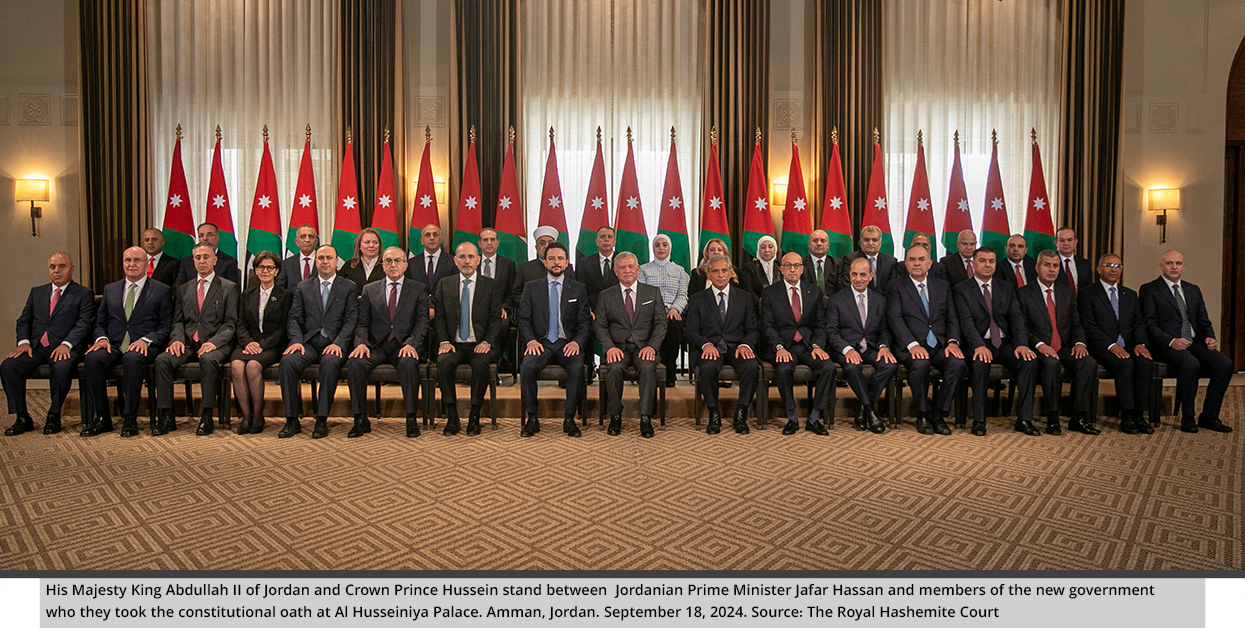

Objectively, the inclusion of members from these parties in Prime Minister Jaafar Hassan’s government—such as government communication minister Mohammed Al-Momani, who is also the National Charter party secretary general; Eradah Party member Khair Allah Abu Sa’leek, who was appointed as minister for Public Sector Development and Secretary-General of the Taqadum Party Khaled Bakar, who also heads the Ministry of Labor—indicates an implicit coalition or an expectation of formal registration during the council’s sessions. Without this, justifying their selection over others would be challenging for the government

On the other hand, the existence of a party coalition with a majority benefits both the coalition itself and the government, as it allows control over the council’s bodies, committees, and presidency. The National Charter Party is seeking to chair the council, as stated by its representative, Mazen Al-Qadi, who has nominated three of its members for this purpose, among them former Speaker of the House Ahmad Al-Safadi.

This is in exchange for support from other parties in securing seats in the permanent office and committees, enabling these parties to share control over the council’s bodies and thereby initiate control over the council’s agenda, priorities, and outputs. Additionally, such a coalition balances their electoral weight in the general constituency against that of the Islamists, having received approximately 475,000 votes compared to 460,000 for the Islamists.

However, all potential coalition components face other factors that may undermine the chances of achieving this alliance. Both parties with significant seats, the National Charter and Eradah, have their own aspirations and ambitions, whether in terms of parliamentary work or participation in future governments. Joining a single parliamentary bloc could compromise their ability to distinguish themselves from one another, particularly in the public eye and regarding their differing party programs.

Second: Formation of an Opposition Minority

Consultations conducted by Prime Minister Hassan, particularly his decision to meet with members of the Eradah and the National Charter parties first—despite their current lack of larger parliamentary blocs—suggest that the upcoming government anticipates a potential merger of these blocs or at least their support base to counter parties that have defined their opposition stance. Regardless of party coalition dynamics in the council, a spectrum of like-minded parties possesses a larger number of seats compared to the 31 members of the Islamic Action Front.

These parties are likely to act cohesively, especially regarding their relationship with the government and their stance on domestic and foreign policies, whether collectively or individually. This indicates that the Islamic Action Front may position itself as an opposition force, possessing enough influence within the council to affect the agenda without being able to obstruct it. While they have the required number of seats to influence the council’s proceedings, they cannot hinder the quorum for meetings or block laws needing a two-thirds majority, nor can they effectively propose or vote on no-confidence measures.

Scenario Three: A Parliamentary Composition That Diminishes the Effectiveness of Party and Parliamentary Blocs

The majority of the 20 council members are party-affiliated, with expectations of 5 to 7 parliamentary blocs forming after the council convenes. While this party landscape offers equal opportunities for various parties to hold influence over the council’s agenda and decisions, it faces challenges regarding the ability of these blocs, particularly the party-affiliated ones, to maintain cohesion among their members.

On one hand, several new parties dominate the parliamentary scene, having little prior experience in parliamentary work, making it premature to assess their strength and resilience. This is not only in relation to the Islamic Action Front but also against their fellow members, who were propelled into the council by their electoral constituencies. Some members bring significant experience that predates their parties’ formation, which may grant them considerable influence within their parties. Notably, many of these parties gained seats through local rather than general constituencies, with candidates from local lists sometimes receiving around 35% of the total votes for their party locally, and approximately 20% in the general list.

On the other hand, the electoral law did not establish regulations for party candidates on local lists, failing to define the relationship between a deputy and their party, except for those from party lists in the general constituency. Article 58, clause four, states that if a deputy elected from a party list resigns or is expelled, the vacant seat must be filled by the next candidate on that list. Consequently, parties may face challenges in managing their successful deputies from local lists, who comprise 67 members in total. This number is notably higher in some parties compared to those from general lists, with the National Charter Party having 26 out of 30 members and Eradah Party having 16 out of 21.

Scenarios for the House of Representatives and the Path of Political Modernization

The House of Representatives faces a significant test in its performance, given its fundamentally different composition compared to previous councils. The 20th council is viewed as a laboratory for parties to gradually increase their allocated seats in upcoming elections. Consequently, the impact of the soon-to-convene House extends beyond parliamentary work to influence the entire trajectory of reform and political modernization. Any success achieved by the council will contribute positively to this modernization path, while any setbacks could adversely affect it.

Thus, the appropriate criteria for moving to the next step of modernization can be outlined as follows:

1- Organizie the party landscape to help ensure quality parties and reduce the overcrowding in the party system that accompanied the elections, where 36 parties participated but only 10 won seats.

2- Foster parties capable of enhancing the political landscape and provide diverse voting options for citizens, especially with the upcoming 21st House of Representatives elections, which will increase the party list share to 50% of the council seats.

3- Uphold the principle of separation between the executive and legislative branches, ensuring a healthy relationship between the government and the House of Representatives.

4- Improve the quality of parliamentary performance and increase public satisfaction with the House of Representatives, positively impacting voter turnout in future elections.

Scenario One: Success of the Experiment and Transition to the Next Step of Modernization

The upcoming House of Representatives, given its current composition and various scenarios outlined above, is likely to support the government. On one hand, a majority of new parties control the parliamentary landscape, comprising 73 members or 53% of the total. Their coalition could strengthen their voting power against the IAF in the general constituency. Additionally, there is a significant bloc of independents, which, if reduced, is expected to ultimately support the National Charter and Eradah parties. Furthermore, there are party figures within the upcoming government.

On the other hand, the Islamic Action Front, classified as part of the opposition in the House, has declared its intention to avoid a confrontational approach with the government. Notably, it has representatives in the Royal Committee for Political Modernization and participated in consultations with the prime minister-designate before the announcement of the government’s formation. This indicates that it is involved in shaping the current political landscape and shares national and popular responsibility for its success. Unlike previous experiences where it monopolized party representation, the IAF now faces other parties within the current council, countering the predominance of independents.

On another note, the structure of the 20th council is conducive to developing the party landscape in Jordan. For instance, three majority party blocs constitute 58% of the council, facilitating the National Charter and Eradah parties in building a popular base and social support similar to that of the Islamic Action Front. This also keeps the door open for smaller parties to adopt popular policies or merge with larger ones.

Moreover, considering the changing circumstances and factors, new parties have better prospects in the upcoming 21st House of Representatives elections compared to the last ones. The potential increase in voter turnout could enhance their chances of securing seats on party lists, especially since the IAF has reached its limits in mobilization. Additionally, the changing rules for candidate selection allowed the IAF to attract influential figures to its list, helping it gain votes from provinces beyond its traditional support base.

Scenario Two: Limited Success of the Experiment and Electoral Law Amendments

Limited success in the experiment would mean that parties meet the requirements for parliamentary work and improve legislative life, positively impacting public trust in the House of Representatives, which has suffered declines in recent years. This applies to all parties, particularly in terms of the ability of government-participating parties to balance public and political responsibilities, as well as the IAF’s capacity to engage in responsible and mature opposition, avoiding political bickering, pressure, or obstruction of policies both inside and outside the council.

However, this success may not necessarily translate into popular support for the new parties, which theoretically require many years to establish their grassroots bases and transition from relying on socially influential figures to becoming programmatic political parties that meet national aspirations. These parties are currently facing a real test in avoiding the pitfalls of becoming personal, service-oriented, or factional parties.

In this case, it is likely that the government or the House of Representatives itself will preempt the 21st council elections by making amendments to the 2022 electoral law. This could resemble the first amendment to Article 49 in June 2024 that reduced the threshold for local lists from 7% to 1%. This change allowed for a greater number of local lists, resulting in more elected deputies compared to the previous situation of having only one or two lists. Consequently, this had a positive impact on new political parties, which heavily relied on local lists to bring their members into the council

Thus, this scenario envisions that the House of Representatives will meet all the criteria supporting the transition to the next step of modernization, except for the qualification of parties capable of enhancing the plurality of the party landscape in the 21st House of Representatives elections.

Scenario Three: Setback of the Experiment and Change in the Electoral Law

The state places significant importance on the path of the Royal Committee for Political Modernization. However, there is a widespread recognition of the sensitivity of the political modernization process compared to economic and administrative reforms. Its success largely depends on social components and political parties and is intertwined with various considerations, including voter behavior, party practices, the balance between the executive and legislative branches, and the overall shape of the political landscape. A disruption in any one of these considerations could negatively impact the political modernization process as a whole.

In the case of the 20th council, despite the availability of supportive data for the success of the experiment, the surrounding concerns are equally significant, particularly regarding the behavior of political parties. On one hand, the IAF is likely to form the cornerstone of the opposition in the House of Representatives since it has the necessary numbers to exert effective opposition. However, the exact framework for the opposition that the IAF seeks remains unclear, especially regarding whether it is based on participation or confrontation. Each option would have different implications for the IAF itself, its relationship with the government, and the path of political modernization.

The Islamic Action Front recognizes that the benefits of a participatory approach completely contradict its populist policies and rhetoric. This necessitates a continued confrontational stance in its relationship with the government and the state, which could negatively impact the political landscape. The IAF may justify its positions based on the substantial voting power it received—nearly half a million votes—making it a theoretically strong card for the party. This leverage will persist unless other parties manage to form alliances or coalitions that match or surpass that electoral strength.

Moreover, the IAF preemptively assessed the performance of the new government by criticizing its formation in a statement released September 18, 2024, that described it as “contrary to the will of the Jordanian street as expressed in the elections,” even though it announced after meeting with the prime minister that it did not seek participation in the government.

On the other hand, new parties play a critical role in the success or failure of the political path. If the practices of their deputies reflect individualism and repeat the same mistakes made by some members of the previous council—two of whom were referred to state security courts—this would signal the unfitness of these parties despite their positions being aligned with the government.

Furthermore, the reform path in Jordan has long been intertwined with external conditions and factors. The national agenda faltered in 2005 due to regional circumstances associated with the violence in Iraq. Similarly, the events in Syria since 2012 and their negative impact on Jordan's security hampered the outcomes of the national dialogue initiated in 2011. Currently, the modernization efforts face the repercussions of the war in Gaza and the West Bank and the accompanying regional escalation. This situation has previously allowed armed groups along the Jordanian border to exploit the conflict to intensify their hostile activities. Iran and its proxies have also sought to capitalize on the public sentiment sympathetic to Gaza, opposing official stances regarding the war.

Moreover, the Muslim Brotherhood believes it has achieved its best electoral results inJordan’s history. Given the weakened branches of the group across the region and the divisions between the center and its branches, the Brotherhood may attempt to position itself as the regional and international center of gravity for the group. This could potentially turn Jordan into a battleground for political Islam activities or a launching pad for interventions in the affairs and issues of other countries.

STRATEGIECS Team

Policy Analysis Team

العربية

العربية