“Spearhead” is Getting Ready for the Wars of the Future: U.S Special Forces’ Limits in Contemporary International Conflict.

Strategic assessment | This assessment examines the transformations to the role of U.S. Special Operations Forces, which have declined as asymmetric conflicts have given way to the return of symmetric conflicts in the international strategic environment. The assessment addresses the role of U.S. Special Forces within the framework of new security and defense strategies."

by Anas Al Qasas

- Release Date – Mar 21, 2023

At the end of February, during the annual meeting of the U.S. National Defense Industrial Association, U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflicts Christopher P. Maier stated that the generally recognized role of the Special Operations Command (SOC) at the forefront of the U.S. military activities was diminishing during the recent period, as asymmetric conflict waned and symmetric conflicts returned to influence the strategic environment of the international conflict.

Maier said the pivotal role of the Special Operations Force (SOF) in countering terrorism had patterned itself after the SOC’s role in counterterrorism operations, and that many have forgotten other important roles of the U.S. military’s operational structure in implementing the national defense strategy. Among these, the SOF still plays a major role in countering the Russian operation in Ukraine through the trainings and the partnerships carried out with the Ukrainian Army over eight years.

Maier’s observations followed similar statements by U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Jonathan Braga, commanding general of the Army Special Operations Command. During the Global SOF Foundation’s 2022 Modern Warfare Week[LM1] in November, one of the biggest annual events for the special operations community, Braga said that the U.S. special forces succeeded in implementing their part in transforming the special forces of the Ukrainian army from the Soviet model to the NATO standard, noting, “Our irregular warfare contributions are proving effective on Ukraine’s battlefield today.” Braga’s remarks echoed the comments of commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command Gen. Richard D. Clark in his testimony before the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee on April 5, 2022.

U.S. Special Forces: Major Shifts

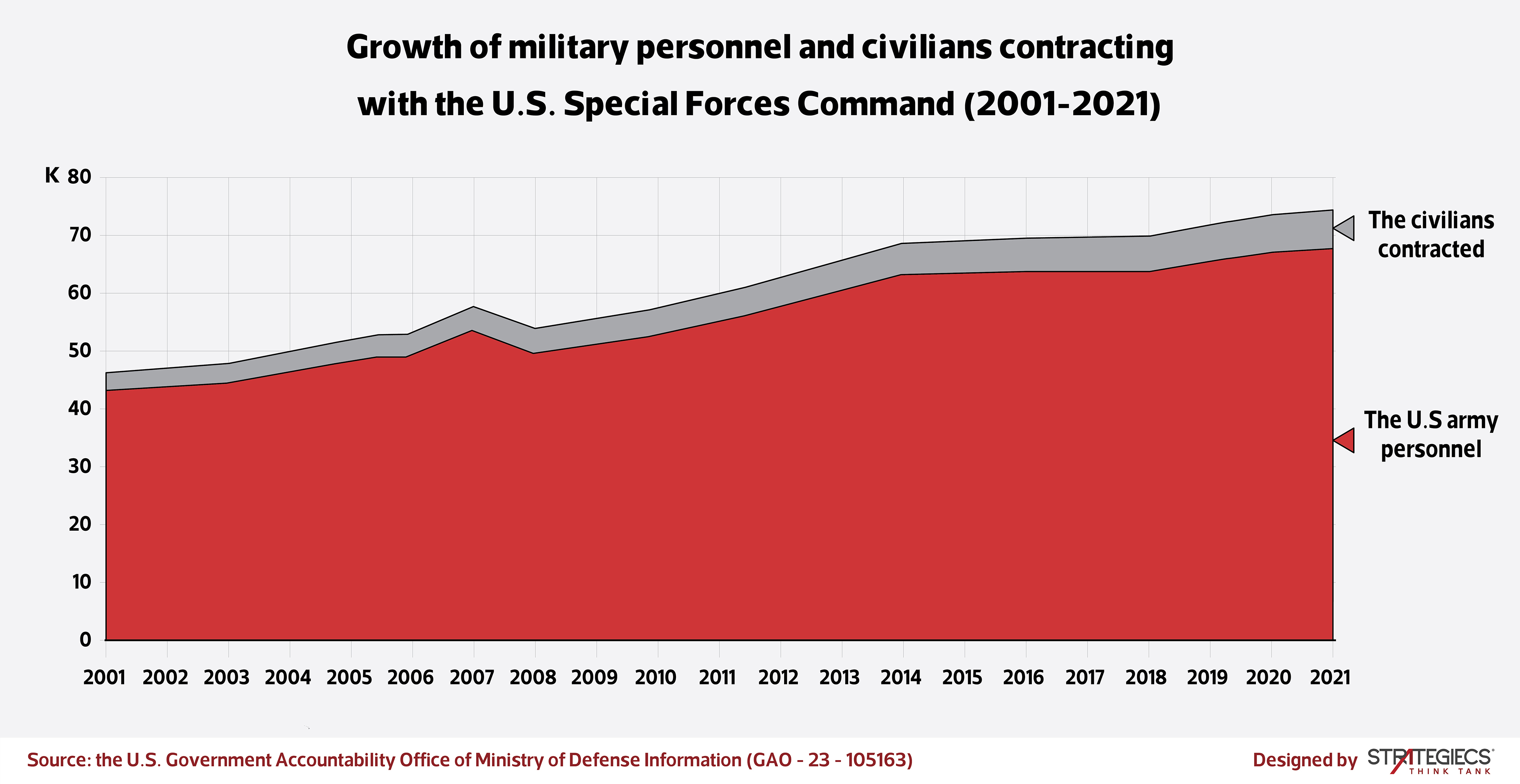

The United States nearly doubled the size of its special forces in response to the 9/11 attacks, declaring war on terror as a top priority. The number of U.S. special operations forces increased from approximately 45,000 personnel in 2001 to 73,900 in 2021, according to a report issued October 2022 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), known as “the investigative arm of Congress.”

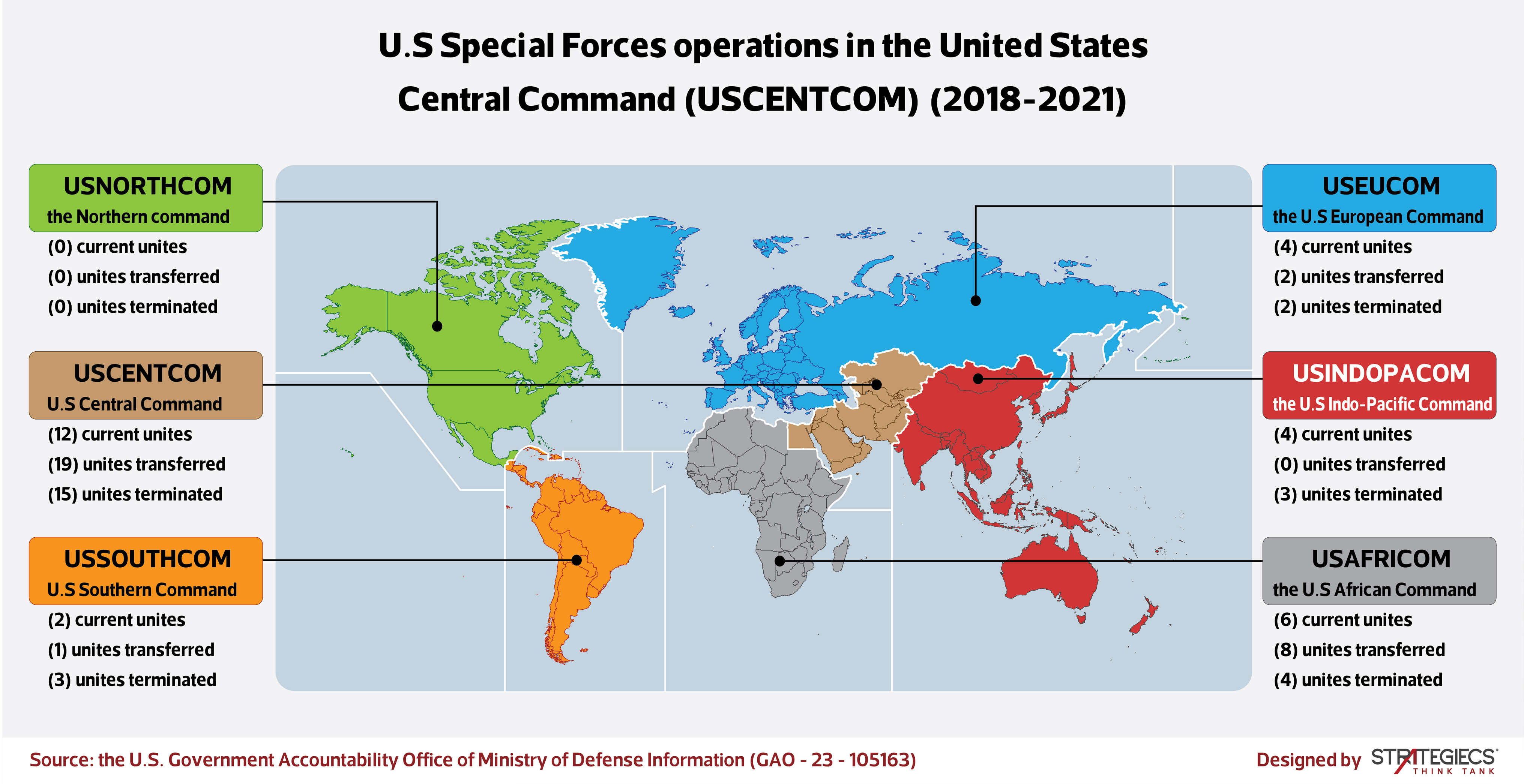

According to a U.S. GAO report, the U.S. Special Operations Command adopted a variety of command and control (C2) structures, depending on the requirements of each geographic combatant command around the world. In 2018, the U.S. Army had 85 active Special Forces units. But of these units, 57 were disbanded or their command was retransferred to other combat commands or missions, thus only 28 units of the U.S. Special Forces units remained in their default state until 2021.

According to the same report, most decisions on disbanding or redeploying units to other branches or weapons were made by the U.S. Central Command Special Forces Command that operates in the Middle East, as the tasks of 34 out of the 46 units were either terminated or transferred, leaving only 12 units in service in their old status. In addition, the Special Operations Command of African Command terminated or transferred 12 out of its 18 units, leaving only six units as they were. Despite all this, however, both units lead the ranking in the number of U.S. Special Forces units, with a total of 18 out of the 28 U.S. Special Forces units.

A Decisive Response to the Transformations of the International System

Forces structures of great armies usually indicate the shape of international conflict as well as any changes that may occur in the conflict environment. If we consider that the international system has quantitative and qualitative characteristics, then the forces structures of the major world powers are the clearest expression of the trends and the aspects that can be noticed in the international conflict.

Consequently, the massive changes to the structure of the U.S. Special Operations Forces came in response to U.S. national strategies, foremost of which are the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy, which have set strategic priorities the U.S. armed forces should adhere to and implement.

Among these huge changes is the decline of the war on terrorism that has been replaced by confrontation with China, which is struggling to lead the international system. War on terrorism was also replaced with confronting Russia, which is trying to seize the opportunity in Ukraine to change the geopolitical situations, not only in the European continent but throughout the Great Eurasian Plain and the Eurasian Steppe, extending from Manchuria (on the Pacific Ocean) to the heart of the European continent. Russia is also struggling to change what it can change in the international system, its regional and subregional spectrums and components.

Significant changes to the U.S. Special Forces role, whether is scale or intensity, can be related to the Trump administration’s 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy. The priority of special operations in the context of the overall U.S. security and defense institutions strategy has gradually faded while focusing on the activities of U.S Special Forces other than counterterrorism activities, such as work to prevent the proliferation of WMDs, psychological warfare, and work within the framework of joint task forces to curb symmetrical threats by some states (China, Russia, and Iran in particular) in the Nonpacific, Europe, and the Middle East.

With the huge changes that followed the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic and its undeniable effects on the international security system, the new U.S. administration came to enhance this strategic view by redefining the priorities of the Special Operations Command, carrying on a similar approach to that adopted by the Trump administration.

With the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis in the winter of 2022, the Biden administration augmented this approach to the U.S Special Forces Command by increasing its role in training allies, opening logistical supply routes, and guarding such routes to Ukraine at times.

The Role of Special Forces in the Framework of New Security and Defense Strategies

The National Defense Strategy issued in the fall of 2022 is based on several main pillars, the most important of which is the security environment that was changing over the past two decades. These changes led to an increase in the traditional threats coming from defense and security institutions in China and Russia. Accordingly, the approach of special operations forces has been engineered according to that variable.

The SOF’s Vision and Strategy paper for Special Operations Command issued last year considered China and Russia to be the main threat sources in the international strategic environment, with less consideration for Iran, North Korea, and extremist terrorist organizations. Based on this, U.S. special operations will establish their operational tracks according to this vision.

The strategic paper added concerning the rivalry with China and Russia, the Special Forces Command will upgrade its forces over the next ten years, taking the dynamic, pioneering, and unconventional approach, and fully updating the full toolset associated with irregular warfare, as well as leveraging emerging technologies to limit China’s hostile activities, and creating asymmetric advantages for current and future conflict.

With Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the start of low-intensity conflicts in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, the United States and its NATO allies played key roles in helping Ukraine prepare to confront the Russians by providing security and intelligence assistance as well as military training.

According to U.S. military commanders, led by Gen. Clark, the Command carried out some qualifying exercises for the Green Berets (U.S. elite forces) under the Q course, which is a program implemented by the 10th Special Operations Group of the U.S. EUROCM. That has led to a doubling of the number of Ukrainian special forces since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, even before the current crisis in Ukraine.

According to several reports, the 10th Special Operations Group remained present on Ukrainian territory even after February 2022, carrying out training and logistical supply for military and civilian aid to the Ukrainian interior. This was hinted by U.S. Army Secretary Christine Wormuth in an interview with the Atlantic Council in May 2022. There was also an announcement last fall by Gen. Braga regarding upgrading some psychological warfare exercises with Ukraine.

In addition, U.S. news reports in February indicated requests by the U.S. Department of Defense for Congress to resume some covert special operations programs in Ukraine, especially a psychological warfare program, suspended with the outbreak of the current crisis, in addition to a request to bring in and train alternative forces (surrogates) to work with the Ukrainian special forces in the framework of unconventional resistance operations directed against Russian military and paramilitary forces.

Training is not limited to the Ukrainian forces or to the European theater. According to many reports, U.S. Special Forces training rates for Taiwanese forces have increased since 2021, as the Green Berets raised the efficiency of Taiwanese forces to counter threats and strengthen defenses against any potential Chinese war on the island. In the same vein, the U.S. Special Forces upgraded their training programs to the Japanese forces in Okinawa, the Japanese island closest to Chinese shores, as well as with the Philippine and Australian militaries.

The U.S. Special Forces are exceptionally tightening their grip on East Africa, implementing the strategy of securing sea lanes and combating terrorism and armed insurgency posed by al-Qaeda-linked groups in the region, with Somalia’s al-Shabaab at its core. In line with that approach, President Biden rescinded an earlier Trump decision and sent 400 members of the Special Operations Forces as additional reinforcements to the region to join the African Special Operations Forces operating in the East, SOCAFRICA (the East Africa Special Operations Task Force), the Joint Special Operations air forces in Africa, the Naval Special Warfare Group TEN, the Special Operations Command Forward - North and West Africa (SOCFWD-NWA), as well as the Joint Special Operations Task Force – Somalia (JSOTF-SOM).

On the other hand, with the increasing security threats from the Arctic, and the special operations forces of the Northern Command SOCNORTH, are conducting intensive exercises in the Alaska region with Canadian forces in the northern Canadian provinces, in connection with joint exercises of the U.S. Special Forces of the European Command SOCEUR, and with Danish and Norwegian forces in Greenland, Iceland, and the Northern Norwegian islands in the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea, in order to raise the efficiency of these forces to reconnoiter and deal with threats.

U.S. Special Forces and a New Era of Threats

As conventional threats and symmetrical conflicts return, challenges for states are increasing in how to form comprehensive and integrated deterrence forces to meet these challenges. But the current conflict environment is not one-sided, as traditional threats usually coincide with an escalation of asymmetric threats, especially when it comes to great-power conflicts, that can threaten on more than one axis. Hence, the U.S. military increasingly relies on special operations forces as a spearhead in countering these threats.

However, with the exceptional circumstances that called for doubling the number of special operations forces during the last two decades, especially the increase of low-intensity conflicts represented by terrorism and armed insurgency, and with the increasing role of armed non-state actors as an inevitable result of global development and openness, American institutions tried to bring back special operations forces to their normal position as elite forces, the matter that requires adjustments in the size, structure, and tasks of forces. Reviewing this year’s published summary of the National Defense Authorization Act, no structural expansions were mentioned for U.S. Special Forces Command, except for expanding the functions of the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations.

On the contrary, there have been many cuts in the troop budget, considering the groups of operations that were disbanded or transferred to other strategic branches, a challenge that the Special Forces Command is trying to address, despite the increasing desired goals of special forces in the context of the Ukrainian crisis, and the comprehensive changes that occurred in the international conflict environment in the last two years.

In addition to counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, and counter-threat of violent non-state actors (VNSAs) missions, the Special Operations Forces’ missions have expanded to include training and upgrading allied forces to increase their effectiveness, and securing supply lines, logistics, and maritime inspections as part of counter-proliferation and nuclear operations, particularly in the Indo-pacific and Middle East.

The U.S. Army upgrading plan, which is being discussed extensively these days, also entails complex roles for the Special Forces Command, especially developing amphibious operations via light personnel carriers, in which Navy Special Forces are expected to participate with the Marines.

In light of these challenges, a major role is emerging for the U.S. Special Operations Command, which has become required to deal according to a budget that is gradually contracting, while the tasks required of these forces are expanding, during their response to the variables of the strategic environment and their threats. These variables will lead to fundamental changes in the track, course, and shape of Special Forces in a new world of hybrid threats.

* The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author. Strategiecs shall bear no responsibility for the views and/or opinion of its author on security, economic, social, and other issues, as they do not necessarily represent the views of the Think Tank.

Anas Al Qasas

Expert on strategic and international affairs, war and peace issues

العربية

العربية