Ba’ath Regime in Syria Has Fallen. So When Do the Sanctions Fall?

The economic sanctions imposed by many countries on Syria—which are still in place—have led to restrictions on foreign trade, the freezing of Syrian assets abroad, and the prevention of necessary investments and aid for the country’s reconstruction. Therefore, lifting the sanctions on Syria remains the most crucial step in rebuilding the devastated Syrian economy, which will, in turn, serve as a foundation for establishing civil peace and coexistence, both of which will be undermined if the sanctions continue.

by Hasan Ismaik

- Release Date – Jan 5, 2025

The legacy left by the fall of the Ba’ath regime in Syria is no small or trivial matter, especially in various aspects of the state and its sectors. I believe it becomes even more complicated and burdensome in the economic field. Every number, indicator, and statistic in the Syrian economy raises concern and reflects a near-total collapse of the economic system—if such a system even existed in the first place. In fact, it is debatable whether the term “system” is appropriate to describe the Syrian economy.

Syria’s infrastructure has suffered extensive destruction, sabotage, and looting, with the most significant losses being in the country’s core sectors. The agricultural sector was hit the hardest, severely affected by population displacement, the destruction of farmland, and the rising costs of production. Similarly, the industrial sector saw the destruction of many factories or their shutdowns due to energy shortages, lack of raw materials, and a shortage of labor. Finally, the services sector was also significantly impacted, suffering from the deterioration of security and stability, as well as the flight of investors.

Estimates indicate that Syria’s economic losses have exceeded $650 billion. In addition, millions of Syrians have been displaced internally or have fled the country, leading to a massive loss of qualified labor. This, in turn, has increased the production burdens on the remaining workforce. Today, more than 14 million Syrians live below the poverty line, with the majority suffering from severe food insecurity. Unemployment rates have soared, while “hidden unemployment” within government institutions has also proliferated, further exacerbating the economic burdens on families.

Moreover, the value of the Syrian pound has plummeted significantly, with the exchange rate reaching 15,000 pounds to the U.S. dollar, while the average monthly wage remains below $17. This has led to a sharp rise in import costs, a decline in citizens’ purchasing power, and the inability of most people to meet even their basic needs

Of course, let us not forget the economic sanctions imposed by many countries on Syria that have led—and continue to lead—to restrictions on foreign trade, the freezing of Syrian assets abroad, and the prevention of necessary investments and aid required for the country’s reconstruction. These sanctions have exacerbated the challenges faced by Syria, further hindering any prospects for recovery or rebuilding.

I used the term “Ba’ath regime” at the beginning of this article not because I shy away from naming individuals or avoid assigning responsibility, but rather because I want to emphasize that the destruction of Syria’s economy is not the result of former President Bashar al-Assad alone nor is it solely the consequence of the recent war. The roots of this devastation go back decades, beginning long before the current conflict. The damage traces back to when the Ba’ath Party, with its socialist ideology, took control. This ideology, when combined with corruption, nepotism, wars, and sanctions, led to catastrophic results that the Syrian people now bear the full brunt of, paying the price alone.

The Ba’athist regime left a deep mark on Syria’s economy, beginning with the nationalization of many key industries and vital sectors. This diminished the role of the private sector, stifled entrepreneurial spirit, and hindered innovation. The implementation of a centrally planned economy in which the state alone determined prices, production, and distribution led to significant bureaucracy and rampant corruption. A system of nepotism emerged in which family members and friends were given priority for jobs and contracts, leading to the loss of talent abroad and a rise in unemployment rates. Corruption became the most prominent and visible feature at all government levels, resulting in the waste of resources and the erosion of trust in state institutions. Subsequently, the war dealt the final blow to an already fragile and crumbling economy.

Is There a Way Out?

It can be said that the biggest obstacle to rebuilding the Syrian economy has been removed, and by this, I mean the Ba’athist regime with all its members who operated both openly and behind the scenes. However, this in no way means that the task ahead is easy or that the road to recovery is smooth and straightforward. The new authorities still face the challenge of tackling this deep-rooted and complex economic crisis. The process of reconstruction will require massive investments in infrastructure and essential services, and it will certainly need international support and assistance that goes beyond the capabilities of just one or two countries.

This necessitates a global consensus, leading to broad international participation in supporting Syria and rebuilding its economy first before then extending it to all aspects that are inevitably tied to the economy and depend on its recovery. Thus, lifting sanctions on Syria remains the most crucial step in rebuilding the country’s devastated economy, which will, in turn, serve as a foundation for establishing civil peace and coexistence—both of which will be undermined if the sanctions continue.

I have received perspectives from some circles of decision-making, both Arab and Western, which suggest that the current situation indicates that Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) may prefer to empower its loyalists. There are significant concerns that granting them control over economic activities, in addition to political and social ones, could lead to the creation of an Islamist version of the economic governance previously seen under the regimes of the Ba’ath Party and the Assad family. For a long time, this system was marked by corruption, favoritism, and those in power treating the country as their personal property. Such a development would necessarily impact the issue of lifting sanctions, as they primarily affect and thus punish the average Syrian citizen.

Currently, any statement, position, or action that suggests the new leadership in Syria is indifferent to the West’s opinion or its role in the future of Syria signals a short-sighted, poorly judged, and stubbornly narrow perspective. This was the previous leadership’s viewpoint, and it led the country to the brink of disaster, complete isolation from its Arab surroundings and the international community, and total subjugation to Tehran’s will, which was only concerned with its own interests at the expense of the Syrian people.

The Syrians have a painful history with actions that disregard the West and its power, especially in the economic domain. Any rhetoric in this context inevitably reminds them of past statements—“Look to the East!”, “Erase Europe from the map!”, “Revive the five seas!”—among other empty slogans that only resulted in impoverishing Syrians and worsening their living conditions.

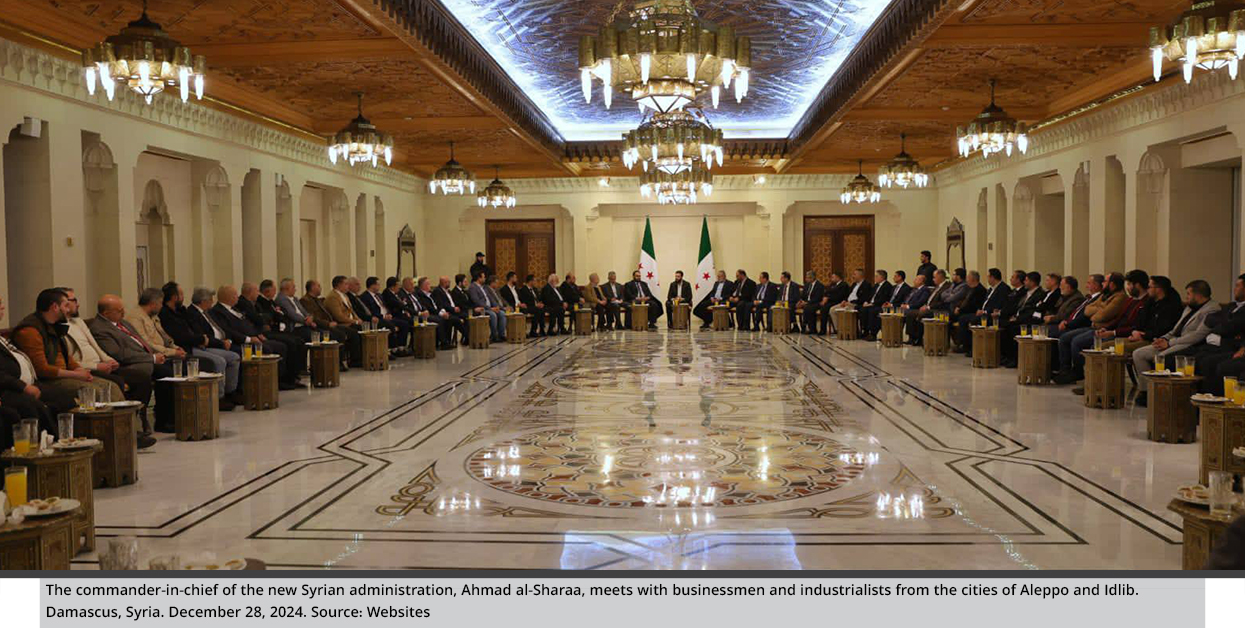

Similarly, in the context of not repeating the previous approach, the Assad regime adhered to a winner-take-all mentality. Therefore, HTS leader Ahmad al-Sharaa and his team must distance themselves from adopting this mindset. Otherwise, the system of government in Damascus will soon face the same challenges that led to the collapse of the previous regime.

On December 30, the interim government in Syria appointed Mayssa Sabreen as the new head of the Central Bank of Syria. As a former deputy governor of the bank and the first woman ever to be appointed to this position, her nomination sent two reassuring messages: Syria’s new leaders recognize the need for technocrats—even those who were part of Assad’s regime—and they will not exclude women from public life.

More messages of reassurance, both in word and in action, are absolutely essential today on all fronts. While it is clear from diplomatic movements, both Arab and international, that there is a serious shift toward considering the easing of sanctions, actual changes will primarily depend on the measures taken by the new Syrian leadership regarding power-sharing, transitional justice, human rights, and public freedoms. The international community will remain cautious, and any lifting of sanctions will be accompanied by significant internal reforms to ensure long-lasting peace and stability.

Syria Has Room for Everyone

What I have said previously does not imply that Syria’s reconstruction or investment in any of its sectors is merely an act of charity or goodwill. Rather, it is a genuine economic opportunity and a potential source of substantial profits. The investment prospects in Syria are many and diverse, extending beyond traditional sectors such as oil, gas, and agriculture, though these remain important. For example, the services sector in Syria can be a huge source of profit. The country possesses vast untapped potential and a young, ambitious generation that has borne but has not been broken by the weight of tyranny. Now, with its wings unshackled, this generation is ready to soar high and far in the realms of science, art, creativity, and innovation.

In addition, there are the Syrian migrants, numerous and widespread, who have gained diverse experiences and knowledge. Given the right conditions, they can bring their acquired skills back to serve their homeland, contributing to its rebuilding and development.

Syria is an ancient country, literally as old as recorded history, with a rich and diverse culture, and a persevering people who have proven beyond a doubt their ability to bring about positive change, no matter how difficult or seemingly impossible. If given the opportunity to harness and propel their energies through modern regulatory laws, legislative frameworks, and open strategies, the Syrian people can transform their country from a state of collapse and fragmentation into a major engine of economic opportunity—not only for the Syrians themselves but for Arab and foreign investors.

In conclusion, the fall of the Assad regime has brought about a seismic shift in Syria’s governance dynamics. The new administration led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham is still grappling with finding a delicate balance between its ideological foundations and the pragmatic necessities of governing. Yes, the narratives surrounding the speed and nature of the regime’s fall remain contradictory to this day. Yet despite the limited certainty about what truly transpired, there is one undeniable fact: The primary factor behind the regime’s collapse was the continuous economic decline that deteriorated all aspects of Syrian life over the past thirteen years.

Therefore, the economy must be given paramount importance because it is the foundation upon which the state will be rebuilt in all its aspects. After all, it is the health of the economy that determines the eventual success or failure of any ruling authority.

Today, Syrians, across all affiliations and spectrums, show an unprecedented readiness to take charge of their country’s affairs. A society that has lived under the weight of dictatorship for half a century is now prepared to overcome its fear of rulers. In response, the interim leadership must fulfill its crucial role in guiding all Syrians to work together as one people, moving away from divisive formats and destructive ideologies. Taking this approach will mark the first step in a long journey to building a free, stable, and prosperous Syria.

This path forward is not only vital for Syria’s recovery, it offers this weary and war-torn country the potential to become an inspiring model for any country around the world facing internal conflicts or civil wars.

Hasan Ismaik

STRATEGIECS Chairman

العربية

العربية