The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author. Strategiecs shall bear no responsibility for the views and/or opinion of its author on security, economic, social, and other issues, as they do not necessarily represent the views of the Think Tank.

Al-Qaeda Post-Zawahiri: Structure, Crisis, and Future

Position Assessment| This article seeks to extrapolate the fate of al-Qaeda after the demise of its leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri. Such exploration analyzes the reality of al-Qaeda at its structural and operational levels; the crises it is suffering; and the future of al-Qaeda as well as its branches, and the prospects for change in al-Qaeda’s ideological discourses, network of relations, and positions on the ground.

by Maher Farghali

- Publisher – STRATEGIECS

- Release Date – Sep 13, 2022

Introduction

Killing al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri opened the door for speculation about the future of al-Qaeda organization, the future strategy of its network, and how its crises will manifest itself. What are those manifestations, challenges, and problems that will face al-Qaeda? The crisis of Zawahiri’s succession and who the potential candidates are to succeed him has been talked about for a long time. This paper will answer within three ideas: Zawahiri’s Qaeda structure and capabilities;

- al-Qaeda’s crisis during the past three years; and al-Qaeda organization reality and future.

It can be said that al-Qaeda, contrary to what is said about its fall, was able to rebuild its combat capabilities in the three years preceding the killing of its leader al-Zawahiri. Al-Qaeda expanded its network of alliances, moving from vexation to mastery of warfare to conduct a process of integration of its regional branches.

On the other hand, al-Qaeda led by al-Zawahiri faced several problems due to the loss of most of its leaders and influencers, in addition to the internal disagreement over the strategy of globalized and local fighting, as well as other issues that may affect al-Qaeda’s future.

However, al-Qaeda will not be greatly affected by al-Zawahiri’s death. It will go beyond that by changing its traditional form and inventing new organizational patterns in a way that leads us to expect al-Qaeda’s traditional form to come to an end, turning it into a new organization.

Zawahiri’s Qaeda structure and capabilities

The cautious optimism about the fall of al-Qaeda during the Zawahiri era was relatively inaccurate. This organizationx was able to withstand several threats and setbacks it suffered in this period between 2019 and 2022. Some believe that the organization succeeded in building its combat capabilities, expanding its alliances, and moving from the “vex” jihad to “empowerment.” In addition, al-Qaeda was able to integrate its branches and associated groups, and consolidate its ideological transformations by drifting to further extremism and radicalism. The indications of such successes are:

First: Building Combat Capabilities

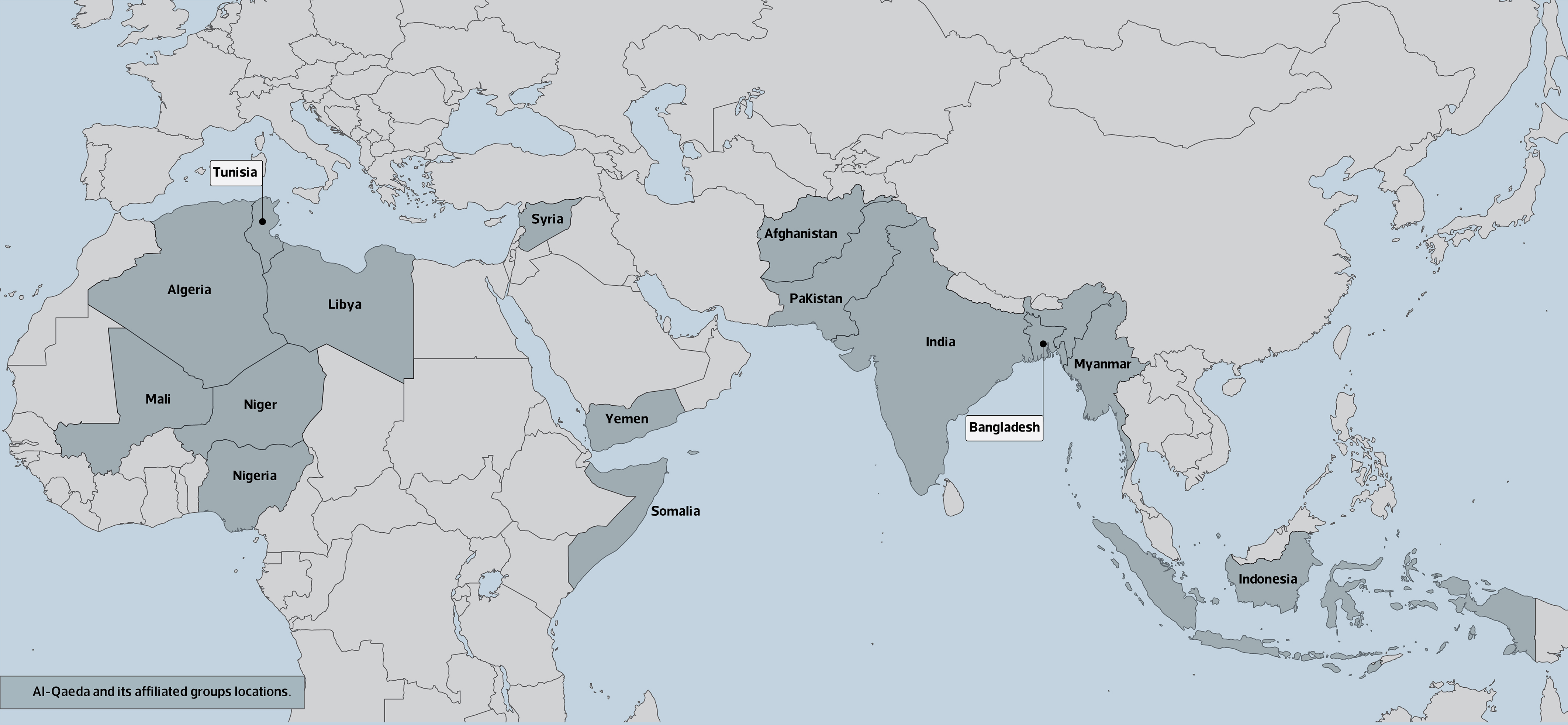

Al-Qaeda pushed its associated terrorist groups to employ their resources and alliances with local fighters and arrange their interests via maintaining their safe havens in parts of Somalia and West Africa, as well as pockets in Libya and Yemen. An increase in the activity of these groups and the development of their combat capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic were noticed. The number of Al-Shabaab Al-Mujahideen operations in Somalia increased to nearly 562 operations during the first half of 2021. In Kenya, Al-Qaeda-linked groups carried out nearly 31 operations. Thirty-five operations were also carried out in Mali. Those operations used unconventional weapons, attacks on difficult and unexpected targets, new methods of detonation, and the use of various explosive materials.

The same period also saw new funding methods, entirely dependant on gold mines in northern Ghana, Togo, Mali, Niger, and others, plus ransom claims for kidnappings, such as the kidnapping of the 83-year-old American nun in Burkina Faso on April 5, 2022, for which the group “Nusrat al-Islam Walmuslemeen” (Support of Islam and Muslims) claimed responsibility.

Second: al-Qaeda Area and Alliances Expansion

Al-Qaeda expanded its presence in Africa after heading from northern Mali southwards to Burkina Faso. This expansion was made through its alliance with Ansar al-Islam. Such expansion extended to Niger, which the group took as its recruitment headquarters after allying with Abdallah Chikau Group before he was killed. Ansar al-Islam, a splinter group of Boko Haram, later pledged allegiance to ISIS.

What was alarming was al-Qaeda’s serious efforts during the previous three years to build its own fighting structure independent from the Taliban in Afghanistan, through an alliance with Asim Omar, al-Qaeda’s leader in South Asia, with organizations and groups such as Askar Janjawi al-Alami, Jundallah, Askar al-Islam, Jabhat Saad ibn Abi Waqqas, Tawhid wa Jihad, and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. (Omar was later killed in a joint Afghan military operation).

At the same time, the al-Qaeda maintained close ties to the Haqqani Network. In Pakistan, it was associated with the Gul Bahadir group, which is allied with the Haqqani Network. (The two groups are from the Mehsud tribe.)

In Syria, al-Qaeda maintained a presence through its affiliate Hurras al-Deen group and also managed to remain in Libya, as well as the Sahel Emirate, via its links to Nasr al-Islam.

Thus, under Zawahiri, al-Qaeda took major foundational steps. These included Following up on pressure on the Uzbek group and the Pakistani Taliban to turn them into a “Salafi-jihadi” ideology; pursuing —despite the siege on the organization’s branches in Africa—recruitment and training, especially in the tribal areas of Waziristan, which includes a number of Arab fighters; establishing local terrorist groups in some areas of Syria and Mali; expanding to new stations such as Benin, Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso; and approaching gold mines in Senegal.

Third: Moving From Vexation to Mastery

Al-Qaeda succeeded, practically speaking, in moving from the “vexation” to “mastery” jihad, as well as land capturing. This emerged in parts of Syria, Mali, and Somalia, where the organization’s branches and groups are content with local activity without talking about the cross-border internationalization of its activities.

Fourth: Adopting Merging Pattern

Al-Qaeda merged the groups associated with it or loyal to it under the umbrella of a joint and unified leadership within a single organizational structure as an alternative to the traditional pattern based on ideological similarity derived from the previous decentralized action strategy. The new al-Qaeda pattern can be called “single-chain organizations.”

It is noteworthy that the merger of the allied organizations under the leadership of al-Qaeda was not followed by the abandonment of the former’s names in favor of the parent organization. This formula gives such organizations flexibility in the operational framework by maintaining their specificity in management, leadership, and choice of tactics. We find that Ansar al-Islam, which includes 10 different groups, claims responsibility for its attacks in its name. It even claims responsibility for attacks outside its theater of operations, such the Wahat attack in Egypt's western desert in 2017.

Fifth: Moving to New Safe Heavens

Al-Qaeda succeeded in expanding into new arenas in North Africa and Southeast Asia to compensate for the loss of support and training centers in Afghanistan. It needs to find new theaters of operations that give it sufficient operational flexibility to finance and implement its operations. Al-Qaeda achieved this through its aforementioned alliances, in addition to groups such as Abu Sayyaf, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, and other small groups.

Maher Farghali

Researcher specializing in extremism and terrorism issues

العربية

العربية